Mechanical Engineering · Thermal Expansion Equation

Thermal Expansion Equation – predicting dimensional change with temperature

The thermal expansion equation lets you estimate how much a material grows or shrinks as temperature changes, so you can size gaps, joints, and supports that survive real-world heating and cooling without jamming or cracking.

Quick answer: what the thermal expansion equation tells you

Core linear thermal expansion formula

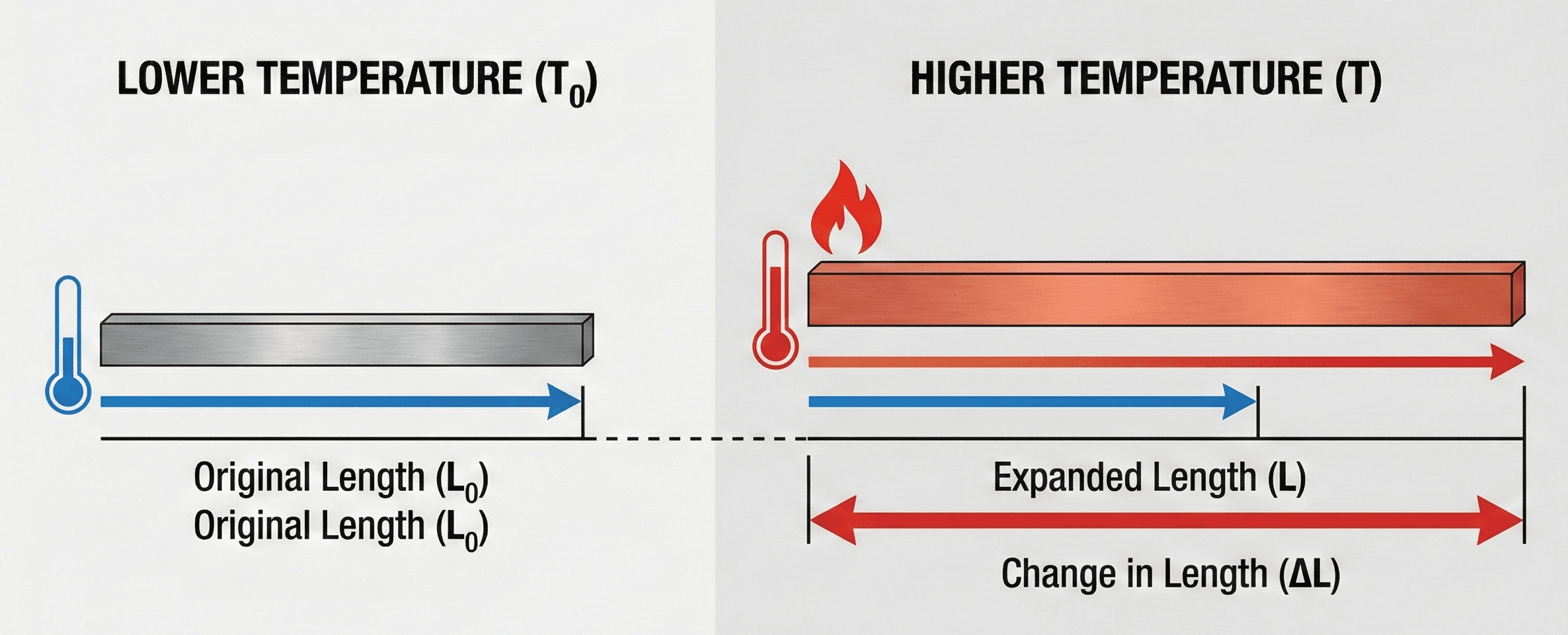

The thermal expansion equation says that, over typical engineering temperature ranges, the change in length \(\Delta L\) of a solid is proportional to its original length \(L_0\), the temperature change \(\Delta T\), and a material property called the coefficient of linear thermal expansion \(\alpha\).

In everyday engineering, the thermal expansion equation is the workhorse for “how much will this move when it gets hot?” calculations. If a steel bridge deck sees a seasonal swing of tens of degrees, or a long process pipe warms from ambient to operating temperature, \(\Delta L = \alpha L_0 \Delta T\) gives a first estimate of how far anchors, guides, and joints need to accommodate that motion.

The equation is deliberately simple: it assumes the temperature is uniform through the material, the coefficient \(\alpha\) is roughly constant over the temperature range of interest, and the material expands isotropically (the same in all directions). Within those limits, it does a remarkably good job of predicting dimensional change and is built into design rules for civil structures, mechanical systems, piping, HVAC, and even electronics packaging.

If you want to experiment with different materials, lengths, and operating temperatures without doing the math by hand, you can plug the same equation into the Thermal Expansion Calculator and instantly see the resulting dimensional changes for your specific problem.

As you will see again in the worked examples, thermal expansion is rarely huge by itself (often fractions of a millimeter per meter of length), but over long runs or tight fits it can make or break a design. That’s why standards, building codes, and equipment manuals routinely quote thermal expansion coefficients and temperature ranges.

Symbols, units & notation in the thermal expansion equation

In its most common one-dimensional form, linear thermal expansion is written as \( \Delta L = \alpha L_0 \Delta T \), where \(\alpha\) is the coefficient of linear thermal expansion. For area and volume, similar relationships exist, but the length-based form is the starting point for most design checks. The table below summarizes the symbols and typical engineering units you will see.

Common notation

| Symbol | Quantity | SI Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( \Delta L \) | Change in length | meter (m) | Increase or decrease in length due to temperature change. Positive \(\Delta L\) usually means expansion; negative \(\Delta L\) means contraction. |

| \( L_0 \) | Original length | meter (m) | Length at the reference temperature (often installation or a specified “cold” condition). The thermal expansion equation scales linearly with \(L_0\). |

| \( \Delta T \) | Temperature change | kelvin (K) or °C | Difference between final and initial temperature, \( \Delta T = T_\text{final} – T_\text{initial} \). In differences, 1 K and 1 °C have the same magnitude. |

| \( \alpha \) | Coefficient of linear thermal expansion | 1/K or 1/°C | Material property describing how much a unit length expands per degree of temperature increase. Typical values are around \(10^{-6}\) to \(10^{-5}\,\text{K}^{-1}\) for metals. |

| \( \varepsilon_\text{th} \) | Thermal strain | – (dimensionless) | Strain caused purely by temperature change: \( \varepsilon_\text{th} = \dfrac{\Delta L}{L_0} = \alpha \Delta T \). This becomes important when converting expansion into stress. |

| \( \beta \) | Coefficient of volumetric expansion | 1/K or 1/°C | For volumetric changes, \( \Delta V = \beta V_0 \Delta T \). For isotropic solids, a good approximation is \( \beta \approx 3 \alpha \). |

Unit systems & practical notes

- SI (standard for most engineering work): use lengths in meters, \(\Delta T\) in kelvin or °C, and \(\alpha\) in 1/K or 1/°C. Because a degree kelvin and a degree Celsius have the same size, you can treat 1/K and 1/°C as interchangeable for temperature differences.

- Imperial / U.S. customary: lengths are often in inches or feet, and \(\alpha\) is tabulated in 1/°F. Be consistent: if \(\alpha\) is in 1/°F, \(\Delta T\) must be in °F, and lengths should all use the same unit.

- Typical magnitudes: steels often have \(\alpha \approx 11\text{–}13 \times 10^{-6}\,\text{K}^{-1}\), aluminum around \(22\text{–}24 \times 10^{-6}\,\text{K}^{-1}\), and concrete somewhere between them depending on aggregate. Plastics and elastomers can be much higher.

How thermal expansion connects temperature and dimensional change

At the atomic level, solids are made of atoms vibrating around equilibrium positions in a lattice or amorphous network. As temperature increases, those vibrations become more energetic and the average spacing between atoms increases. On the macroscopic scale, that microscopic spacing change shows up as a slightly larger length, area, or volume – the phenomenon we call thermal expansion.

For most engineering materials over modest temperature ranges (say, tens of degrees), the relationship between strain and temperature is close to linear. We capture that with a proportionality constant \(\alpha\), the coefficient of linear thermal expansion, and write the thermal strain as \( \varepsilon_\text{th} = \alpha \Delta T \). Multiplying by the original length converts that strain into an actual dimensional change.

Linear, area & volumetric forms

The most useful engineering relationships for thermal expansion follow from the definition of thermal strain. Starting from the idea that thermal strain is proportional to temperature change, you can build the familiar formulas:

For surfaces and volumes, similar expressions hold. For an isotropic solid, expansion is the same in all directions, so area and volume changes can be approximated using multiples of \(\alpha\):

These area and volume forms show up in tank sizing, fluid thermal expansion, and stress checks on enclosed liquids and gases. But in day-to-day structural and mechanical design, the simple linear form \( \Delta L = \alpha L_0 \Delta T \) is usually the primary tool, especially when you are worried about the motion of a particular dimension or clearance.

Defining the coefficient of thermal expansion

The coefficient of linear thermal expansion \(\alpha\) can be defined directly from experimental measurements of length change with temperature. If you measure the length of a specimen at two temperatures and assume \(\alpha\) is constant over that interval, you can write:

Rearranging gives the familiar working equation again:

Data tables for structural steels, aluminum alloys, copper, concrete, and many other materials quote average \(\alpha\) values over specific temperature ranges. When accuracy matters, check that your problem’s temperature range matches how the data were measured; at cryogenic or very high temperatures, \(\alpha\) can vary significantly with temperature.

From free expansion to thermal stress

When a component is free to expand and contract, thermal expansion only changes dimensions and clearances. But if expansion is fully or partially restrained, thermal strains turn into stresses via Hooke’s Law. In the simplest 1D case of a fully restrained bar:

Here \(E\) is Young’s modulus and \(\sigma_\text{th}\) is the thermal stress that would develop if the bar is prevented from changing length. In real structures and piping systems, supports, anchors, and flexibility share that strain, but this simple relationship explains why long restrained members under large temperature swings can crack, buckle, or overstress welds.

The thermal expansion equation assumes uniform temperature through the cross-section and along the length of the member. If you have strong temperature gradients (hot on one side, cold on the other) or very large \(\Delta T\), reality departs from the simple model and you may need more advanced analysis. Still, the linear form is the right starting point, and it underpins the more detailed methods you would reach for in finite element or piping stress software.

Worked examples using the thermal expansion equation

These examples mirror common questions engineers and students ask when searching for the thermal expansion equation: how much does a member grow over a seasonal temperature swing, what gap is needed at an expansion joint, and how do you back-calculate \(\alpha\) from test data. All three use the same core relationship \( \Delta L = \alpha L_0 \Delta T \) with different unknowns.

Example 1 – Expansion of a steel bridge girder over a temperature swing

A simply supported steel girder in a bridge has an original length of \(L_0 = 30~\text{m}\) at a reference temperature of \(-5^\circ\text{C}\). On a hot day, the girder temperature rises to \(30^\circ\text{C}\). Assuming a coefficient of linear thermal expansion \( \alpha = 12 \times 10^{-6}~\text{K}^{-1} \), how much does the girder lengthen?

- Compute the temperature change \(\Delta T\).

- Apply \( \Delta L = \alpha L_0 \Delta T \) with consistent units.

- Convert the result to a more intuitive unit (millimeters) and interpret it.

Result: The 30 m girder lengthens by about \(12.6~\text{mm}\) between the cold and hot conditions. That is a small shift compared to the total span, but it is large enough that bearings, deck joints, and rails must be detailed to accommodate this movement without binding.

Example 2 – Required expansion gap for a hot process pipe

A straight run of stainless-steel process pipe is anchored at one end and guided along its length. The pipe run is \(L_0 = 50~\text{m}\) long at an installation temperature of \(20^\circ\text{C}\). In service, the pipe can reach \(80^\circ\text{C}\). Take \( \alpha = 17 \times 10^{-6}~\text{K}^{-1} \) for stainless steel. What movement should the guide system or expansion joint be able to accommodate at the free end?

- Determine the temperature increase from installation to operating condition.

- Use \( \Delta L = \alpha L_0 \Delta T \) to calculate end movement.

- Round up to a reasonable design value with some margin.

Result: The pipe run will try to grow by roughly \(51~\text{mm}\) as it heats from 20°C to 80°C. The expansion joint or guided support at the free end should comfortably accommodate this movement (often with additional margin for higher temperatures, construction tolerances, and support flexibility).

Example 3 – Back-calculating \(\alpha\) from laboratory measurements

A 1.000 m long sample of an unknown metal alloy is measured in a lab. At \(20^\circ\text{C}\), its length is \(L_0 = 1.000~\text{m}\). At \(80^\circ\text{C}\), its length is \(L = 1.0014~\text{m}\). Assuming linear behavior over this range, what is the average coefficient of linear thermal expansion \(\alpha\)?

- Compute the change in length \(\Delta L\) and temperature change \(\Delta T\).

- Start from the definition \( \alpha = \dfrac{1}{L_0} \dfrac{\Delta L}{\Delta T} \).

- Evaluate \(\alpha\) and compare it to typical handbook values to guess the material type.

Result: The measured alloy has an average coefficient of linear thermal expansion \( \alpha \approx 23 \times 10^{-6}~\text{K}^{-1} \), which is in the same range as common aluminum alloys. This kind of back-calculation is how many data tables are generated and verified.

Design tips, limits & checks for using the thermal expansion equation

In practice, the thermal expansion equation is almost always combined with structural capacity checks, support layouts, and code requirements. The relationship \( \Delta L = \alpha L_0 \Delta T \) is simple, but the way you apply it can make a big difference to reliability. The points below highlight common assumptions, pitfalls, and sanity checks that come up in design reviews.

Before trusting a thermal expansion estimate, make sure the underlying assumptions are reasonably satisfied for your situation:

- The material is homogeneous and isotropic, or at least behaves similarly in the direction of interest.

- The temperature through the member is approximately uniform; strong gradients can cause bending and warping beyond simple axial expansion.

- The coefficient \(\alpha\) is roughly constant over the temperature range you are using; this is usually fine for moderate swings around room temperature.

- The member is free to expand and contract in the direction you are analyzing, or you explicitly handle restraint when converting expansion into stress.

- Mixing units: using \(\alpha\) tabulated in 1/°F with \(\Delta T\) in °C (or vice versa), or mixing inches and meters for lengths, can give errors of nearly a factor of two.

- Ignoring differential expansion: bolting steel to aluminum, or attaching metal parts to concrete, without checking how differently they expand across the operating range can crack coatings, overstress bolts, or warp assemblies.

- Forgetting the installation temperature: designs are often built at some intermediate “shop” or ambient condition. What matters is the full range from that installation temperature to the extremes of service, not just the operating setpoint.

- Assuming full restraint when it is not present (or vice versa): using \(\sigma = E \alpha \Delta T\) blindly may over- or underpredict thermal stress if supports allow some movement.

Simple mental checks can catch many thermal expansion issues early, before you build a detailed model or push everything into software:

- Compare the predicted expansion to available gaps and clearances. If a 50 m pipe wants to grow by 50 mm and your guides only have 10 mm of play, you need additional flexibility or an expansion joint.

- Translate expansion into thermal stress using \( \sigma_\text{th} = E \alpha \Delta T \) for a fully restrained case and compare to allowable stresses with safety factors. If you are approaching yield, consider more flexibility or lower temperature.

- In assemblies with multiple materials, compare their \(\alpha\) values. If one expands twice as much as another over the same \(\Delta T\), focus your attention on the interface between them.

- Revisit your assumptions if the results look extreme (for example, very large stresses or movements); that may indicate that temperature gradients, nonlinear material behavior, or more detailed support modeling are important.

When your design pushes beyond the simple regime – very long runs with complex support patterns, thin shells with steep gradients, or components cycling through wide temperature ranges – the thermal expansion equation remains the backbone of your intuition. It tells you roughly how much the structure wants to move, which you can then feed into more advanced analysis or commercial piping stress and FEA tools as needed.

Thermal Expansion Equation – FAQ

What is the thermal expansion equation in simple terms?

In simple language, the thermal expansion equation says that when a solid gets hotter, it gets a little longer, and when it cools, it gets a little shorter. The amount of length change is proportional to the original length, the temperature change, and a material-specific constant \(\alpha\). Mathematically, this is \( \Delta L = \alpha L_0 \Delta T \), where \(\Delta L\) is the length change, \(L_0\) is the original length, \(\Delta T\) is the temperature change, and \(\alpha\) is the coefficient of linear thermal expansion.

What units should I use for the coefficient of thermal expansion?

In SI-based engineering work, \(\alpha\) is usually given in 1/K or 1/°C. Because a temperature difference of 1 K is the same as a difference of 1°C, these are effectively identical as long as your \(\Delta T\) uses the same degree size. In Imperial units, \(\alpha\) is often quoted in 1/°F, with lengths in inches or feet. The key is consistency: whatever unit you use for \(\alpha\), use the same temperature unit for \(\Delta T\) and a single length unit for both \(L_0\) and \(\Delta L\).

What is the difference between linear, area, and volumetric thermal expansion?

Linear expansion deals with changes in one dimension, like the length of a bar, and uses \(\alpha\) in \( \Delta L = \alpha L_0 \Delta T \). Area expansion looks at changes in surface area, often approximated as \( \Delta A \approx 2 \alpha A_0 \Delta T \) for isotropic solids. Volumetric expansion uses a separate coefficient \(\beta\) in \( \Delta V = \beta V_0 \Delta T \), with \(\beta \approx 3 \alpha\) for isotropic materials. In many structural and mechanical problems you only care about one dimension, so the linear form is sufficient.

When is the simple thermal expansion equation not accurate enough?

The linear thermal expansion equation is an approximation that works best for moderate temperature ranges and uniform heating. It becomes less accurate when:

- The temperature range is very large, causing \(\alpha\) to change significantly with temperature.

- There are strong temperature gradients through the thickness or along the length, causing bending or warping.

- The material has complex behavior (e.g., phase changes, creep, or highly nonlinear thermal response).

In those cases, you may need temperature-dependent material data and numerical methods (for example, finite element analysis) that integrate expansion over the actual temperature distribution instead of relying on a single average \(\Delta T\).

References & further reading

- Standard engineering materials handbooks and design manuals that tabulate coefficients of thermal expansion for steels, aluminum alloys, copper, concrete, polymers, and composite materials.

- Structural and mechanical design textbooks covering thermal loading, thermal stress, and expansion joint design, often in chapters on temperature effects or load combinations.

- Piping and pressure vessel codes, manufacturer catalogs, and application notes that illustrate how to combine thermal expansion calculations with support layouts, flexibility analyses, and allowable stress checks.