Heat Transfer · Fourier’s Law

Fourier’s Law – heat conduction, temperature gradient & thermal conductivity explained

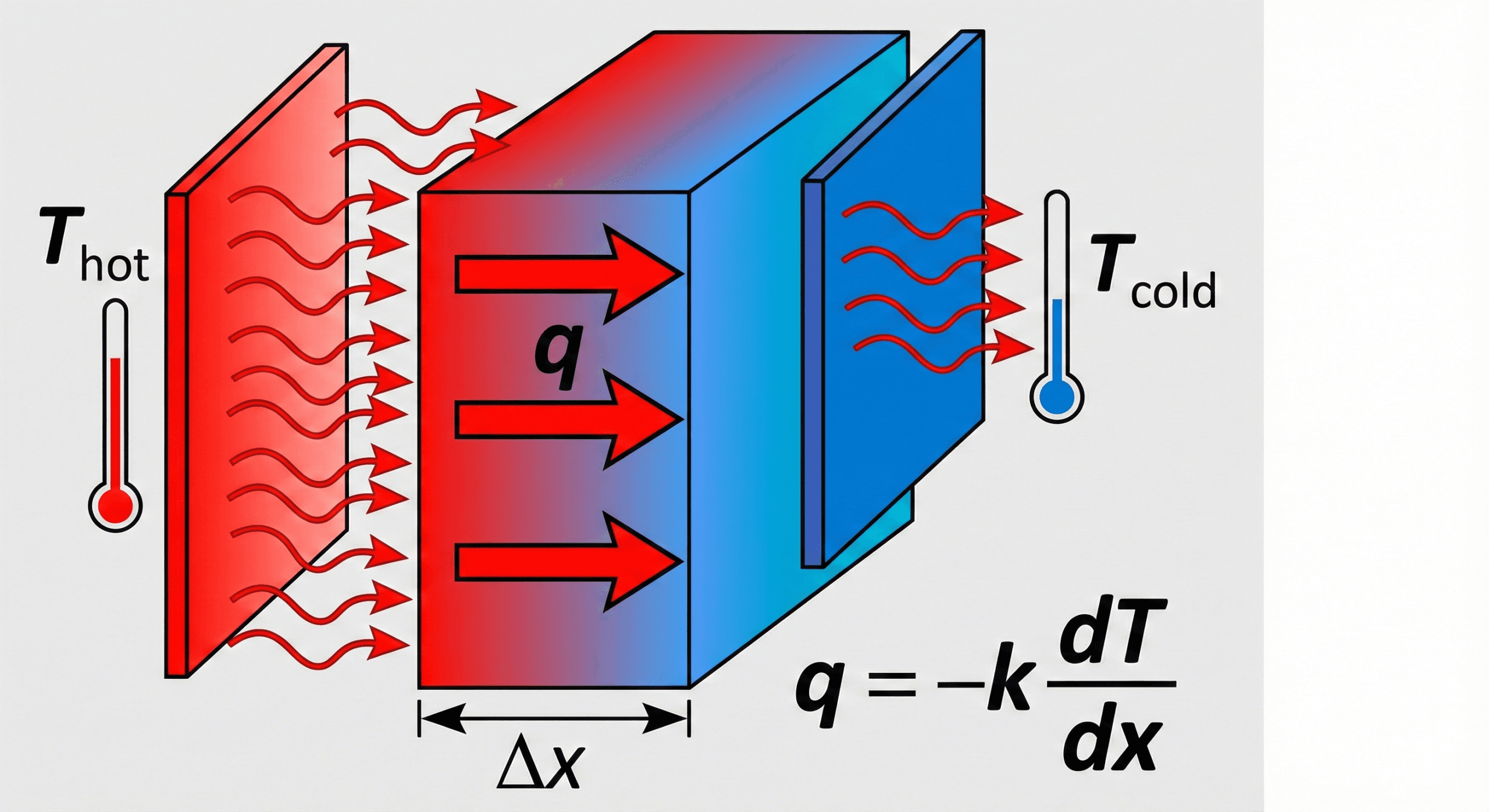

Fourier’s Law links heat flow to temperature gradients and material thermal conductivity, giving you the core equation for one-dimensional wall losses, insulation design, and conduction-dominated heat transfer problems.

Quick answer: what Fourier’s Law tells you about heat flow

Core formula for one-dimensional conduction

Fourier’s Law states that the conductive heat transfer rate \(q_x\) through a solid is proportional to the material’s thermal conductivity \(k\), the cross-sectional area \(A\), and the temperature gradient \(dT/dx\); heat always flows from hot to cold, opposite the direction of increasing temperature.

In practical heat-transfer work, Fourier’s Law is the default tool for conduction-dominated problems. If you know how hot one side of a wall is, how cold the other side is, what the wall is made of, and how thick it is, you can use this equation to estimate how many watts of heat leak through that wall. Once you understand conduction, you can combine it with convection and radiation to size heaters, chillers, or insulation more confidently.

Engineers often use simplified, algebraic forms of Fourier’s Law for common cases such as steady, one-dimensional conduction through plane walls. But underneath those shortcuts, the same fundamental idea is always present: temperature gradients drive heat flow, and the proportionality is set by the material’s thermal conductivity.

Symbols, units & notation in Fourier’s Law

The most general vector form of Fourier’s Law is \(\, \vec{q}” = -k \nabla T \,\), where \(\vec{q}”\) is the heat flux vector and \(\nabla T\) is the temperature gradient. For many engineering calculations, you work in one dimension along \(x\) and either track the heat flux \(q”_x\) or the total heat rate \(q_x\). The table below summarizes common symbols and their typical SI units.

Common notation for conduction problems

| Symbol | Quantity | SI unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( q_x \) | Heat transfer rate | W (watt) | Total heat flow through a surface normal to the \(x\)-direction. Positive in the direction of heat flow by sign convention. |

| \( q”_x \) | Heat flux | W/m² | Heat transfer rate per unit area: \( q”_x = q_x / A \). Often more convenient when comparing different surfaces. |

| \( k \) | Thermal conductivity | W/(m·K) | Material property describing how easily heat conducts through a solid; high \(k\) for metals, low \(k\) for insulators. |

| \( A \) | Area normal to heat flow | m² | Cross-sectional area perpendicular to the direction of heat flow. For a flat wall, this is simply the wall surface area. |

| \( \dfrac{dT}{dx} \) | Temperature gradient | K/m | Rate of change of temperature with position in the direction of heat flow. In steady 1-D walls, it is often constant and approximated as \( (T_{\text{hot}} – T_{\text{cold}})/L \). |

| \( L \) | Conduction path length | m | Distance between the hot and cold surfaces along the heat-flow direction (e.g., wall thickness, insulation thickness). |

Unit systems & quick conversion notes

- SI preferred: Most engineering texts and software assume \(k\) in W/(m·K), distances in m, and temperatures in °C or K (differences are identical in °C and K).

- Imperial / U.S. customary: You may see \(k\) in BTU/(hr·ft·°F). Conversions are straightforward but easy to mishandle; keep units explicit in intermediate steps.

- Sign convention: The minus sign in Fourier’s Law ensures heat flows from hot to cold. When you replace \(dT/dx\) with a finite difference, keep track of which side is “hot” in your coordinate choice.

Once you are comfortable with the symbols and units, the same setup flows directly into the worked conduction examples, where you’ll see Fourier’s Law applied to common wall and insulation problems.

How Fourier’s Law links temperature gradients to heat flow

At a conceptual level, Fourier’s Law plays a similar role in heat transfer that Ohm’s Law plays in circuits or Fick’s Law plays in mass diffusion. A “driving potential” (temperature difference) across a medium with some resistance (set by geometry and material properties) produces a “flow” (heat transfer rate). The more conductive the material, the steeper the gradient, or the larger the area, the more heat flows.

In its differential form for 1-D conduction along \(x\), Fourier’s Law is written as:

Here, \(q”_x\) is the local heat flux, which can vary with position if properties or boundary conditions change. For many design problems, you assume steady state, constant \(k\), and a uniform cross-section, so the gradient becomes linear and the heat flux is constant along the path.

From differential form to simple wall equation

Under steady, one-dimensional conduction through a plane wall with uniform thermal conductivity and no internal heat generation, the temperature profile is linear. Integrating the differential form from the hot side \(x = 0\) at \(T_H\) to the cold side \(x = L\) at \(T_C\) gives a simple algebraic expression:

This is the form most engineers memorize and use directly for “flat wall” problems. It’s the same Fourier’s Law, just integrated over the thickness. Many building, refrigeration, and electronics cooling calculations boil down to rearranging this expression to solve for unknown heat flows, temperatures, or thicknesses.

Thermal resistance viewpoint

It is often convenient to rewrite Fourier’s Law in a format that looks like Ohm’s Law:

Here, \(R_{\text{cond}}\) is the conduction thermal resistance of the layer. Temperature difference \(\Delta T = T_H – T_C\) behaves like a “voltage”, heat flow \(q_x\) behaves like “current”, and thermal resistance plays the role of electrical resistance. Stacking multiple layers in series simply adds their thermal resistances:

This resistance analogy is especially powerful when you mix conduction with convection and radiation, because the same series-/parallel-resistance logic lets you build quick yet accurate composite models of walls, pipes, and multi-layer insulation systems.

In more advanced courses, Fourier’s Law is combined with energy conservation to produce the heat diffusion equation, which describes how temperature changes with time inside solids. Even then, the core physical picture remains: temperature gradients are the “driving force”, and thermal conductivity tells you how efficiently a material responds by conducting heat.

Worked examples using Fourier’s Law

The examples below mirror questions engineers and students actually search for: “How do I calculate heat loss through a wall?”, “What insulation thickness do I need?”, and “How much heat is carried through a composite layer stack?” Each example uses the same basic setup, then adapts Fourier’s Law to a specific design question.

Example 1 – Heat loss through a single, flat wall

A cold room is separated from a warm corridor by a 0.15 m thick brick wall with area \(A = 12~\text{m}^2\). The corridor air is at \(T_H = 22^\circ\text{C}\), and the cold room air is at \(T_C = 4^\circ\text{C}\). Assume the wall is uniform, conduction is one-dimensional and steady, and the thermal conductivity of the brick is \(k = 0.72~\text{W/(m·K)}\). Neglect convection resistance for this back-of-the-envelope estimate. What is the approximate heat loss through the wall?

- Identify hot and cold surface temperatures and wall thickness.

- Compute the temperature difference \(\Delta T\) and conduction resistance \(R_{\text{cond}} = L/(kA)\).

- Apply \( q = \Delta T / R_{\text{cond}} \) or the direct Fourier’s Law form.

Result: The approximate conductive heat loss through the wall is about \(1.0~\text{kW}\). In a real design, you would include inside and outside convection resistances and possibly radiation, but this simple Fourier’s Law estimate already gives a solid sense of the load that the refrigeration system must handle.

Example 2 – Required insulation thickness to limit heat gain

A refrigerated pipe carries a fluid at \(-5^\circ\text{C}\) through a warm space at \(25^\circ\text{C}\). You model the pipe as a flat equivalent wall of area \(A = 5~\text{m}^2\) for simplicity and plan to wrap it in polyurethane insulation with effective thermal conductivity \(k = 0.03~\text{W/(m·K)}\). You want to limit the heat gain through this insulation layer to \(q_{\text{max}} = 150~\text{W}\). What insulation thickness \(L\) is required under steady, one-dimensional conduction assumptions?

- Identify \(\Delta T\), desired maximum heat rate \(q_{\text{max}}\), and material properties.

- Write Fourier’s Law in the algebraic wall form \( q = k A \Delta T / L \).

- Rearrange to solve for the unknown thickness \(L\).

Result: An insulation thickness of approximately \(0.03~\text{m}\) (30 mm) is required to limit the heat gain to 150 W under the simplified assumptions. In practice, you would refine the model to account for cylindrical geometry and include convective resistances, but the Fourier’s Law flat-wall estimate is a useful first sizing check.

Example 3 – Composite wall with multiple conductive layers

A building wall consists of three layers in series: 12 mm gypsum board (\(k = 0.17~\text{W/(m·K)}\)), 100 mm fiberglass insulation (\(k = 0.04~\text{W/(m·K)}\)), and 100 mm brick (\(k = 0.72~\text{W/(m·K)}\)). The wall area is \(A = 20~\text{m}^2\). Indoor air is at \(T_{\text{in}} = 21^\circ\text{C}\) and outdoor air is at \(T_{\text{out}} = -4^\circ\text{C}\). Neglect convection for this example. What is the steady heat loss through the composite wall?

Treat each layer as a conduction resistance and use the thermal resistance form of Fourier’s Law. Sum the resistances to get \(R_{\text{total}}\), then compute the heat flow.

Result: The composite wall leaks roughly \(180\)–\(185~\text{W}\) of heat under the given conditions. The insulation layer dominates the resistance; improving that layer or adding another low-\(k\) layer produces the biggest reduction in heat loss according to Fourier’s Law.

Design tips, limits & sanity checks for Fourier’s Law

In real designs, Fourier’s Law is almost never used in isolation. You combine it with convection correlations, radiation models, and sometimes detailed numerical simulations. Still, the conduction component is often where you start. The points below highlight common assumptions, pitfalls, and quick checks that keep your Fourier-based estimates physically realistic.

The simple algebraic forms of Fourier’s Law rely on assumptions that are fine for many design-level estimates but can break down outside their comfort zone.

- Steady state: temperatures and heat flows are not changing with time (no significant storage effects).

- One-dimensional conduction: temperature varies strongly in one direction, weakly in others.

- Constant properties: thermal conductivity \(k\) does not vary much over the temperature range or with position.

- No internal heat generation: the solid is not producing heat internally (e.g., no electrical resistance heating inside the layer).

- Mixing heat flux \(q”\) and total heat rate \(q\) while forgetting to multiply or divide by area.

- Using the wrong thickness \(L\) (e.g., diameter instead of wall thickness for cylindrical systems).

- Ignoring contact resistances or air gaps between layers that can dramatically reduce effective conduction.

- Applying flat-wall formulas directly to cylindrical or spherical geometries where area changes with radius.

Before finalizing a design or reporting a number from Fourier’s Law, run through a few simple checks:

- Order of magnitude: does the heat loss/gain seem reasonable relative to typical building, electronics, or process loads?

- Material comparison: does swapping in a low-\(k\) insulation layer reduce the heat flow roughly by the ratio of conductivities, as expected?

- Boundary checks: if you double the thickness \(L\), does \(q\) roughly halve? If not, you may have misapplied the resistance form.

When any of these checks fail—or when geometry, property variation, or time dependence become important—the next step is usually to move from closed-form Fourier’s Law calculations to numerical methods (finite difference, finite volume, or finite element) that still rest on the same physical principle but solve more general conduction problems.

Fourier’s Law – FAQ

What is Fourier’s Law in simple terms?

In simple terms, Fourier’s Law says that heat conducted through a solid is driven by temperature differences: the bigger the temperature drop over a given thickness, and the better the material conducts heat, the more heat flows. Mathematically, for one-dimensional steady conduction, \( q = k A (T_H – T_C)/L \): heat is proportional to thermal conductivity \(k\), area \(A\), and temperature difference, and inversely proportional to the path length \(L\).

How do you use Fourier’s Law to calculate heat loss through a wall?

To estimate heat loss through a wall, identify the hot and cold surface temperatures, the wall thickness, area, and thermal conductivity. Then apply the flat-wall version of Fourier’s Law: \( q = k A (T_H – T_C)/L \). For multiple layers, compute each layer’s resistance \(R_i = L_i/(k_i A)\), sum them to get \(R_{\text{total}}\), and use \( q = \Delta T / R_{\text{total}} \). This is the same workflow illustrated in the worked examples.

When does Fourier’s Law not apply directly?

The basic engineering form of Fourier’s Law assumes continuum behavior, relatively slow processes, and well-defined temperatures. It becomes less reliable at extremely small length scales (nanostructures), in materials with highly direction-dependent conductivity, or when heat transfer is dominated by radiation or convection instead of conduction. In such cases, you either extend the model (e.g., anisotropic conductivity tensors) or switch to more advanced transport formulations, but Fourier’s Law remains the starting point for most macroscopic solids.

Is Fourier’s Law the same as the heat diffusion equation?

No. Fourier’s Law is a constitutive relation that links heat flux to the temperature gradient. The heat diffusion equation (or heat equation) is obtained by combining Fourier’s Law with an energy balance in a control volume. The diffusion equation describes how temperature changes with time and space inside a solid; Fourier’s Law provides the conduction term within that equation. In steady one-dimensional problems, the diffusion equation simplifies and you can often work directly with Fourier’s Law in its algebraic forms.

References & further reading

- Standard heat transfer textbooks that introduce Fourier’s Law, thermal resistances, and conduction through plane walls, cylinders, and spheres.

- Application notes from insulation manufacturers that tabulate thermal conductivity values and provide design examples based on Fourier’s Law.

- University lecture notes and open courseware on conduction and the heat diffusion equation, which extend Fourier’s Law to transient and multidimensional problems.