Mechanical Engineering · Acceleration Formula

Acceleration Formula – velocity change, time & distance explained

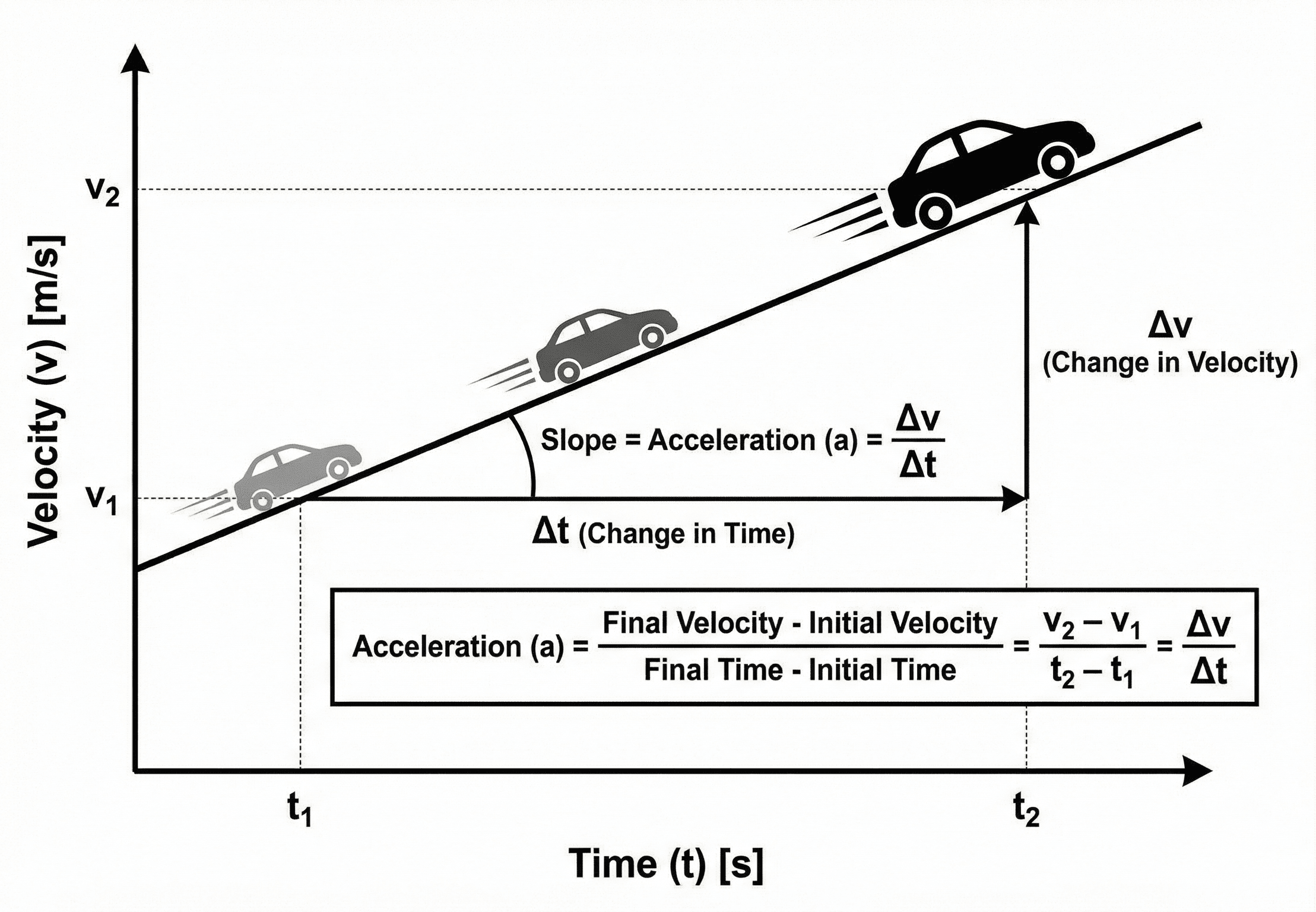

The acceleration formula relates how quickly velocity changes to the time interval and distance over which it happens, giving engineers a simple way to size motions, check loads, and interpret kinematics in real systems.

Quick answer: what the acceleration formula tells you

Core formula (average acceleration)

The acceleration formula says that the average acceleration \(a\) of an object equals the change in its velocity divided by the time over which that change occurs. If velocity changes quickly, acceleration is large; if velocity changes slowly, acceleration is small.

In most engineering and physics problems, “acceleration” is not just a buzzword – it is the link between motion and the forces or loads behind it. The average acceleration formula \( a = \dfrac{\Delta v}{\Delta t} \) is the starting point: it answers questions like “If a car goes from 0 to 20 m/s in 5 s, what is its acceleration?” or “If a conveyor slows from 1.2 m/s to 0.6 m/s over 0.4 s, how strong is the deceleration?”

For constant acceleration, this equation ties directly into the standard kinematic relationships – including \( v = v_0 + a t \), displacement formulas, and velocity–distance relationships – which you’ll see in the worked examples. In more advanced dynamics, acceleration also connects back to force via Newton’s Second Law \( \vec{F}_{\text{net}} = m \vec{a} \), but the kinematic form remains the quickest way to interpret changes in motion from basic measurements.

If you just need to plug in numbers and quickly explore different “what-if” scenarios, you can also use a dedicated acceleration calculator to compute \(a\), \(v\), or \(t\) from the others without doing the algebra every time.

Symbols, units & notation in the acceleration formula

In introductory kinematics, acceleration is defined as the rate of change of velocity with respect to time. For average acceleration over a time interval, you use \( a = \dfrac{\Delta v}{\Delta t} \); for instantaneous acceleration at a specific moment, you use the derivative \( a = \dfrac{dv}{dt} \). The table below summarizes common symbols and engineering units used with the acceleration formula.

Common kinematics symbols

| Symbol | Quantity | SI unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( a \) | Acceleration (average or constant) | m/s² | Rate of change of velocity with time. Positive \(a\) means speeding up in the positive direction; negative \(a\) means slowing down or speeding up in the negative direction. |

| \( v \) | Final velocity | m/s | Velocity at the end of the time interval under consideration. Often written as \(v\) or \(v_f\). |

| \( v_0 \) | Initial velocity | m/s | Velocity at the start of the time interval. In many problems this is zero (starting from rest), but not always. |

| \( \Delta v \) | Change in velocity | m/s | Defined as \( \Delta v = v – v_0 \). The sign of \( \Delta v \) matters and must match your sign convention for the motion direction. |

| \( t \) | Final time | s | Clock time at the end of the interval. In many problems we set \(t_0 = 0\) and use just \(t\) as the elapsed time. |

| \( t_0 \) | Initial time | s | Clock time at the start of the interval; often taken as \(0\) for simplicity, so \( \Delta t = t – t_0 \) becomes just \(t\). |

| \( \Delta t \) | Time interval | s | The duration over which the velocity changes: \( \Delta t = t – t_0 \). The same interval must be used for both \( \Delta v \) and \( \Delta t \). |

| \( s \), \( x \) | Displacement | m | Change in position along a chosen axis. For constant acceleration, it enters related formulas such as \( s = s_0 + v_0 t + \tfrac12 a t^2 \) and \( v^2 = v_0^2 + 2 a (s – s_0) \). |

Units & sign conventions in practice

- SI baseline: use velocity in m/s, time in seconds, and acceleration in m/s². This keeps equations dimensionally consistent and avoids hidden conversion factors.

- Everyday speeds: speeds are often given in km/h or mph. Always convert to m/s before applying the acceleration formula so that your result in m/s² is meaningful.

- Sign matters: choosing “forward” or “upward” as positive means accelerations that oppose the motion come out negative. A negative number does not mean “wrong” – it usually means “acceleration opposite to the positive direction.”

Once your symbols and units are clear, you can compute acceleration or solve for time and velocity either by hand or with the Acceleration Calculator to quickly explore different motion profiles.

How the acceleration formula fits into kinematics

At its core, the acceleration formula measures how “steep” your velocity–time curve is. If velocity increases linearly with time, acceleration is constant; if the velocity curve bends, acceleration changes over time. Engineers use both average and instantaneous acceleration, depending on what data is available and how precise the model needs to be.

Average vs. instantaneous acceleration

The average acceleration over a time interval is defined as

This is often what you compute from measurement data: you know the speed at the start and end of a time window and divide the change by the duration. If the time interval is small, this can be a good approximation for the acceleration at a specific instant.

In the limit of very small time intervals, you get the instantaneous acceleration:

This derivative-based definition is what shows up in more advanced dynamics and control theory, where velocity is a continuous function of time and you want the acceleration “right now,” not averaged over the last second.

Connecting acceleration with velocity & distance

When acceleration is constant – a common assumption in introductory problems and many controlled motion profiles – the acceleration formula combines with the standard kinematic equations. Starting from \( a = \dfrac{\Delta v}{\Delta t} \), you can integrate once to relate velocity and time, and twice to relate displacement and time.

These three equations, plus the definition of average acceleration, form the usual “toolbox” for straight-line motion at constant acceleration. You pick the form that matches the data you know: if you have time, use the first or second; if you have distance but not time, use the third. All of them are just rearrangements and integrations of the same underlying acceleration concept.

Vector acceleration and motion in more than one dimension

In 2D or 3D motion, acceleration is a vector, often written as

The component form of the acceleration formula is the same as in one dimension, but now you apply it separately along each axis. For example, in projectile motion near Earth’s surface, horizontal acceleration is often zero (neglecting drag), while vertical acceleration is approximately \(-9.81~\text{m/s}^2\) due to gravity. Treating each axis separately keeps the math manageable even in complex trajectories.

In summary, the acceleration formula tells you how quickly velocity changes. For simple design checks and homework problems, the average form \( a = \dfrac{\Delta v}{\Delta t} \) and its constant-acceleration companions are usually enough. For high-fidelity models, you combine the same concept with calculus, force models, and numerical solvers to track motion in much finer detail.

Worked examples using the acceleration formula

The examples below show how the acceleration formula appears in realistic scenarios that people commonly search for: “0 to 60” style car questions, elevator comfort limits, and braking distances. The same patterns apply whether you are analyzing lab data, designing a motion profile, or double-checking a simulation.

Example 1 – Car going from 0 to highway speed

A car accelerates from rest to \(27~\text{m/s}\) (about 97 km/h or 60 mph) in \(9.0~\text{s}\) with roughly constant acceleration. Find the car’s average acceleration and the distance traveled in that time.

- Identify \(v_0\), \(v\), and \(t\), and write the average acceleration formula.

- Compute \(a\) using \( a = \dfrac{\Delta v}{\Delta t} \).

- Use a constant-acceleration displacement equation to find the distance traveled.

Result: The car’s average acceleration is \(3.0~\text{m/s}^2\), and it travels about \(120~\text{m}\) while speeding up to highway speed. This is in the ballpark of many everyday passenger vehicles.

Example 2 – Elevator comfort acceleration

A building code guideline suggests that passenger elevators should limit vertical acceleration to around \(1.2~\text{m/s}^2\) for comfort. Suppose an elevator starts from rest and reaches its cruising speed of \(2.4~\text{m/s}\) using this constant acceleration. How long does it take to speed up, and how far does it travel during that interval?

- Use the acceleration formula rearranged to solve for \(t\).

- Compute the time needed to reach the target speed.

- Use the constant-acceleration displacement formula to find the distance.

Result: The elevator reaches its cruising speed in \(2.0~\text{s}\) and moves about \(2.4~\text{m}\) during that acceleration phase. Both the magnitude of the acceleration and the duration are chosen to feel smooth and comfortable for passengers.

Example 3 – Braking distance for a vehicle

A vehicle is traveling at \(22~\text{m/s}\) (about 79 km/h) when the driver applies the brakes and comes to a stop over \(55~\text{m}\) of level road, assuming constant deceleration. Find the vehicle’s acceleration during braking and the time it takes to stop.

This time you know the initial velocity, final velocity, and stopping distance, but not the time. Choose the kinematic formulas that match those known quantities.

- Use \( v^2 = v_0^2 + 2 a (s – s_0) \) to solve for the acceleration.

- Use the acceleration formula in the form \( a = \dfrac{\Delta v}{\Delta t} \) to solve for the stopping time.

Result: The vehicle experiences a deceleration of about \(-4.4~\text{m/s}^2\) and takes \(5.0~\text{s}\) to come to a stop. The negative sign simply indicates that the acceleration is opposite the direction of motion – exactly what you expect for braking.

Design tips, limits & checks when using the acceleration formula

In real engineering work, the acceleration formula is almost always embedded in a larger context: comfort limits, structural loads, friction models, safety factors, and control strategies. The tips below highlight patterns that come up repeatedly when you turn \( a = \dfrac{\Delta v}{\Delta t} \) into design decisions.

The “right” formula is the one that matches the data you actually know. All of the common kinematic equations are just rearrangements of the acceleration definition.

- Use \( a = \dfrac{v – v_0}{t} \) when you know initial and final speeds and the time interval directly.

- Use \( v = v_0 + a t \) when you know acceleration and want to predict velocity after a given time.

- Use \( s = s_0 + v_0 t + \tfrac12 a t^2 \) when you care about distance traveled under constant acceleration.

- Use \( v^2 = v_0^2 + 2 a (s – s_0) \) when you know distance but not time (typical in braking distance or ramp problems).

- Mixing units like km/h and m/s in the same calculation, leading to accelerations off by factors of 3.6 or 3.6².

- Forgetting that \( \Delta v \) and \( \Delta t \) must refer to the same interval (for example, mixing “per second” and “per minute” data).

- Assuming acceleration is constant when it is not – especially in systems with strong drag, friction that changes with speed, or bang-bang control signals.

- Dropping the sign and reporting only magnitudes, which can hide whether the acceleration actually opposes or assists the motion.

Before you trust any acceleration number in a design, sanity-check it against well-known benchmarks and what humans or components can tolerate.

- Compare to \( g \approx 9.81~\text{m/s}^2 \). Accelerations much larger than \(1\text{–}2~g\) quickly become uncomfortable or unsafe for people unless carefully managed.

- Check resulting velocities and distances: does the distance traveled during acceleration fit within the available space, and are the speeds reasonable for the system?

- Consider structural and fatigue effects: high accelerations can create large inertial forces when combined with mass, feeding back into stress and deflection checks.

If these quick checks suggest you are close to comfort or strength limits, that is usually your cue to move beyond hand calculations: refine your model, incorporate load-dependent effects like drag and friction, or run a numerical simulation. The acceleration formula remains the backbone of those more detailed analyses – it just works alongside richer models rather than by itself.

Acceleration formula – FAQ

What is the acceleration formula in simple terms?

In simple language, the acceleration formula says that acceleration equals how much your speed changes divided by how long that change takes. If your speed increases by \(10~\text{m/s}\) over \(5~\text{s}\), your average acceleration is \(2~\text{m/s}^2\). The same idea applies when you slow down – the acceleration is just negative.

How do you calculate acceleration from velocity and time?

To calculate acceleration from velocity and time, identify the initial velocity \(v_0\), the final velocity \(v\), and the time interval \(\Delta t\). Then use \( a = \dfrac{v – v_0}{\Delta t} \). Make sure velocities are in m/s and time is in seconds; otherwise convert units first. If \(v < v_0\), the acceleration will come out negative, indicating deceleration relative to your positive direction.

What are the units of the acceleration formula?

In the SI system, acceleration is measured in metres per second squared, written m/s². That unit literally means “how many metres per second your velocity changes every second.” In many applications you also see acceleration expressed as a multiple of \(g\), where \(1~g \approx 9.81~\text{m/s}^2\). For example, \(3~g\) corresponds to about \(29.4~\text{m/s}^2\).

What is the difference between average and instantaneous acceleration?

Average acceleration uses finite changes: you look at how velocity changed over a specific time interval and compute \( a_{\text{avg}} = \dfrac{\Delta v}{\Delta t} \). Instantaneous acceleration is the mathematical limit as that interval becomes very small, written \( a = \dfrac{dv}{dt} \). In practice, average acceleration is usually enough for design and data analysis, while instantaneous acceleration is more important in detailed models and control algorithms.

References & further reading

- Standard university-level physics and engineering mechanics textbooks that introduce kinematics and the definitions of displacement, velocity, and acceleration.

- Course notes and open-access lectures on introductory mechanics, many of which include detailed examples of using the acceleration formula in straight-line and projectile motion.

- Application notes from elevator, automotive, and robotics manufacturers that discuss comfort limits, safety margins, and typical acceleration ranges for people and equipment.