Solid Mechanics · Mohr’s Circle

Mohr’s Circle – principal stresses, maximum shear & plane stress transformation explained

Mohr’s Circle gives you a fast, visual way to transform plane stresses, find principal stresses, and read off maximum shear stress and their orientations without memorizing a long list of formulas.

Quick answer: what Mohr’s Circle tells you

Core Mohr’s Circle relationships (plane stress)

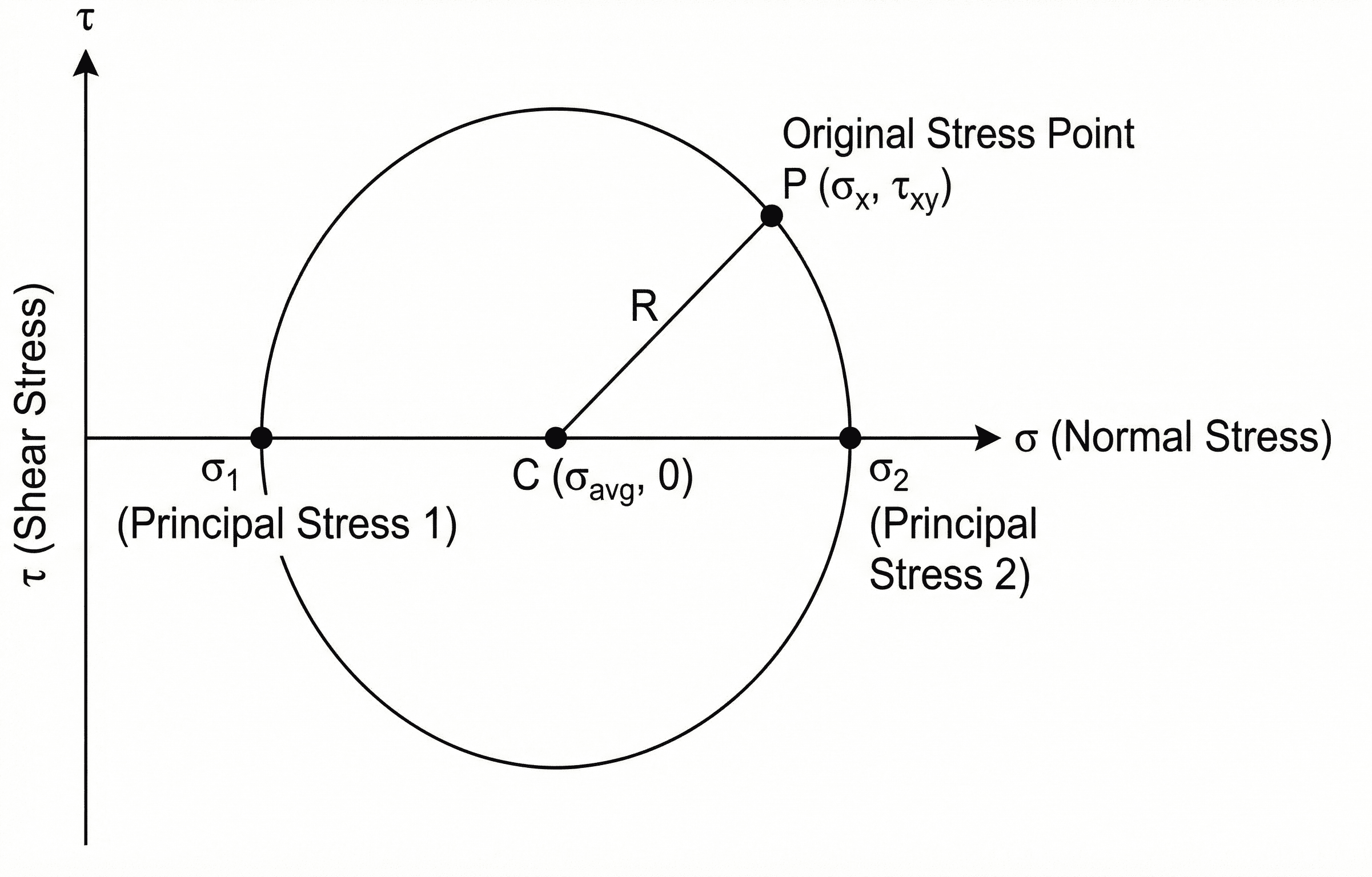

Mohr’s Circle takes any 2D stress state \( (\sigma_x, \sigma_y, \tau_{xy}) \) and maps it to a circle in \( \sigma\!-\!\tau \) space, letting you read off principal stresses, maximum shear stress, and the angles between planes with just geometry.

In mechanics of materials, Mohr’s Circle is one of the fastest ways to answer “what do the stresses look like on another plane?” Instead of plugging into several transformation equations, you sketch a circle based on the original normal and shear stresses, then move around that circle to read off stress components at any orientation. Principal stresses \( \sigma_1 \) and \( \sigma_2 \), as well as the maximum shear stress \( \tau_{\max} \), drop out directly from the geometry of the circle.

For a given in-plane stress state, you first compute the average normal stress \( \sigma_{\text{avg}} \) and radius \(R\). The rightmost point of the circle is \( \sigma_1 \), the leftmost point is \( \sigma_2 \), and the vertical distance from the center gives \( \tau_{\max} \). A factor-of-two relationship between angles on the circle and physical plane orientations ties the picture back to the actual element in the material. Once you understand that mapping, Mohr’s Circle becomes a compact, visual “calculator” for stress transformation and failure checks.

Most students first meet Mohr’s Circle in the context of plane stress (thin plates, surface stresses, beams, and many civil and mechanical components). The same idea extends to plane strain and multi-axial stress, but the two-dimensional circle is the core tool. If you want to jump straight to numeric practice, you can focus on the worked Mohr’s Circle examples below; if you want deeper intuition, the “How it works” section walks through center, radius, and angles in more detail.

Symbols, sign convention & units in Mohr’s Circle

Mohr’s Circle is just a geometric picture of the plane stress transformation equations. To use it correctly, you need clear notation and a consistent sign convention for normal and shear stress. In most engineering textbooks and design codes, the following symbols and units are standard.

Common Mohr’s Circle notation (plane stress)

| Symbol | Quantity | Typical units | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( \sigma_x \) | Normal stress on x-face | MPa, psi | Normal stress acting on the face whose normal points in the \(+x\) direction, resolved in the \(x\)-direction. Often called \( \sigma_x \) or \( \sigma_{xx} \). |

| \( \sigma_y \) | Normal stress on y-face | MPa, psi | Normal stress acting on the face whose normal points in the \(+y\) direction, resolved in the \(y\)-direction (or another chosen axis orthogonal to \(x\)). |

| \( \tau_{xy} \) | Shear stress on x-face in y-direction | MPa, psi | In-plane shear stress acting on the \(x\)-face in the \(+y\) direction. The sign follows the chosen Mohr’s Circle shear convention (often “positive if it would rotate the element counterclockwise”). |

| \( \sigma_{\text{avg}} \) | Average normal stress | MPa, psi | Horizontal coordinate of the circle’s center: \( \sigma_{\text{avg}} = (\sigma_x + \sigma_y)/2 \). |

| \( R \) | Radius of Mohr’s Circle | MPa, psi | Radius of the circle in \( \sigma\!-\!\tau \) space: \( R = \sqrt{ \left((\sigma_x – \sigma_y)/2\right)^2 + \tau_{xy}^2 } \). |

| \( \sigma_1, \sigma_2 \) | Principal stresses | MPa, psi | Normal stresses on planes where shear stress is zero: \( \sigma_{1,2} = \sigma_{\text{avg}} \pm R \), with \( \sigma_1 \ge \sigma_2 \). |

| \( \tau_{\max} \) | Maximum in-plane shear stress | MPa, psi | Equal to the radius of the circle in plane stress: \( \tau_{\max} = R \). Occurs at planes 45° from the principal planes. |

| \( \theta \) | Physical plane angle | deg, rad | Orientation of the new plane measured from the original \(x\)-plane, positive in the chosen sign convention (often counterclockwise). On Mohr’s Circle, twice this angle is used. |

| \( 2\theta \) | Angle on Mohr’s Circle | deg, rad | Angle between the point representing the original stress state and the transformed state on the circle. Rotating the element by \( \theta \) in the physical plane corresponds to rotating the point by \( 2\theta \) on the circle. |

Sign conventions & unit-system notes

- Use a consistent normal stress sign convention: tension positive, compression negative is standard in solid mechanics and makes Mohr’s Circle intuitive.

- For shear, many texts define positive \( \tau_{xy} \) as the stress that tends to rotate the element counterclockwise. Make sure your free-body diagrams match the convention used by your course or code.

- Always keep units consistent (all MPa or all psi). Mohr’s Circle itself is unit-agnostic, but mixing kPa with MPa or psi with ksi will give meaningless results.

Once your sign convention is locked in, Mohr’s Circle becomes a reliable “map” for the plane stress transformation equations. The rest of this guide shows how to build that map and use it for real design decisions, especially in the worked examples section.

How Mohr’s Circle works: center, radius & angles

At its core, Mohr’s Circle is just a re-plot of the plane stress transformation equations. If you start from the algebraic formulas for transformed normal and shear stress, you can group terms to show that any rotated stress state lives on a circle in \( \sigma\!-\!\tau \) space. Mohr’s insight was that this circle captures all possible stress states on planes through a point, so you can read key quantities (like \( \sigma_1, \sigma_2, \tau_{\max} \)) from geometry instead of re-solving the equations every time.

From plane stress equations to a circle in \( \sigma\!-\!\tau \) space

For in-plane stresses on a rotated plane at angle \( \theta \), the transformation equations can be written:

If you square and add these two equations, the cross terms cancel and you get:

This is the equation of a circle of radius \(R\) centered at \( (\sigma_{\text{avg}}, 0) \) in \( \sigma\!-\!\tau \) space. Every possible pair \( (\sigma_{\theta}, \tau_{\theta}) \) for that stress state lies somewhere on this circle. That means:

- The center of the circle represents the average normal stress.

- The radius is equal to the maximum in-plane shear stress \( \tau_{\max} \).

- The principal stresses lie where the circle crosses the \(\sigma\)-axis (because shear is zero there).

The 2θ angle trick: connecting the circle back to the material

A key feature of Mohr’s Circle is the factor-of-two relationship between plane orientation and angle on the circle. If a stress element is rotated by \( \theta \) in the physical plane, the corresponding point moves by twice that angle, \( 2\theta \), on the circle. The direction of rotation depends on the sign convention for shear and the way you draw axes, but the magnitude is always doubled.

Practically, this means:

- The angle between the original stress plane and the principal plane in the material is \( \theta_p \), while the angle from the original stress point to the principal stress point on the circle is \( 2\theta_p \).

- Similarly, the principal planes and the max-shear planes are 45° apart in the material, but 90° apart on the circle.

You can compute the principal plane angle directly from the stress components:

but many engineers instead just plot the original stress point and then “walk” along the circle to the principal points, reading off both stresses and angles graphically. For quick hand checks or exam problems, that is often faster and less error-prone than juggling multiple trig formulas.

Once you are comfortable with center, radius, and the \( 2\theta \) relationship, the rest of Mohr’s Circle is pattern recognition. What used to be several pages of algebra becomes one picture: where the circle intersects the axes, how big it is, and where your current stress state sits around it. The next section turns that picture into step-by-step procedures you can apply to real stress states.

Worked Mohr’s Circle examples

The best way to learn Mohr’s Circle is to draw it for actual stress states that show up in beams, plates, and connections. The examples below walk through: (1) finding principal stresses and maximum shear, (2) checking a material against an allowable principal stress, and (3) seeing how Mohr’s Circle behaves in pure shear. You can reuse the same workflow for homework and preliminary design checks.

Example 1 – Principal stresses & maximum shear from a general state

A point in a steel plate is subjected to plane stresses: \( \sigma_x = 60~\text{MPa} \) (tension), \( \sigma_y = -20~\text{MPa} \) (compression), and \( \tau_{xy} = 30~\text{MPa} \) (shear). Use Mohr’s Circle to find the principal stresses \( \sigma_1, \sigma_2 \) and maximum in-plane shear stress \( \tau_{\max} \).

- Compute the average normal stress \( \sigma_{\text{avg}} \).

- Compute the radius \(R\) of Mohr’s Circle.

- Use \( \sigma_{1,2} = \sigma_{\text{avg}} \pm R \) and \( \tau_{\max} = R \).

Result: The principal stresses are \( \sigma_1 = 70~\text{MPa} \) (tension) and \( \sigma_2 = -30~\text{MPa} \) (compression). The maximum in-plane shear stress is \( \tau_{\max} = 50~\text{MPa} \). On Mohr’s Circle, these appear at the rightmost and leftmost points on the circle and at the topmost point, respectively.

Example 2 – Checking a principal stress against an allowable limit

Suppose the same stress state from Example 1 occurs in an aluminum component with an allowable tensile principal stress of \( \sigma_{\text{allow}} = 85~\text{MPa} \). Use Mohr’s Circle results to check if the component is safe in terms of principal tension.

- Reuse the principal stresses \( \sigma_1, \sigma_2 \) found previously.

- Compare the largest tensile principal stress to the allowable value.

- Interpret the margin and consider real-world factors.

Result: The maximum tensile principal stress uses about 82% of the allowable value in this simple check. Ignoring other modes (like fatigue or buckling), the part is acceptable in terms of principal tension. In practice, an engineer would also look at safety factors, uncertainty in loads, stress concentrations, and other failure criteria (for example, von Mises or maximum shear stress theories), but Mohr’s Circle provides the core principal stress inputs quickly.

Example 3 – Mohr’s Circle for pure shear

Consider a thin plate in pure shear with \( \sigma_x = 0 \), \( \sigma_y = 0 \), \( \tau_{xy} = 40~\text{MPa} \). This might represent the state on a 45° plane of a bar in tension or a thin-walled tube in torsion. Use Mohr’s Circle to find the principal stresses and discuss what the circle looks like.

- Compute \( \sigma_{\text{avg}} \) and radius \(R\).

- Find \( \sigma_1, \sigma_2 \) and \( \tau_{\max} \).

- Interpret the shape and what it says about tension and compression in pure shear.

Result: Pure shear corresponds to equal-magnitude principal stresses in tension and compression: \( \sigma_1 = 40~\text{MPa} \), \( \sigma_2 = -40~\text{MPa} \). On Mohr’s Circle, the circle is centered at zero on the \(\sigma\)-axis with radius \(40~\text{MPa}\). This picture reinforces a common design insight: pure shear is equivalent to tension and compression at 45°, which is why cracks in shear often form on planes oriented around 45° to the applied shear.

Design tips, limits & checks when using Mohr’s Circle

Mohr’s Circle is powerful, but like any tool, it relies on assumptions. In everyday mechanical and civil engineering, you’ll mostly use it for plate-like components, connections, and surface stresses. This section highlights design-oriented patterns: when Mohr’s Circle is the right tool, where it can mislead you, and quick checks that keep your results physically reasonable.

Mohr’s Circle in the form used here assumes plane stress – that is, one normal stress component (often \( \sigma_z \)) is negligible. This is often reasonable for:

- Thin plates loaded in their plane (structural steel plates, gusset plates, sheet metal).

- Surface stresses in beams or shafts (bending plus shear at the outer fibers).

- Connections and welded joints where local geometry is thin in one direction.

It is not appropriate as-is for thick pressure vessels, highly triaxial stress states, or cases where through-thickness constraints generate significant \( \sigma_z \). In those cases, Mohr’s idea still extends, but you need 3D stress invariants or multiple circles instead of a single simple picture.

One of the most common sources of error with Mohr’s Circle is inconsistent sign convention between the element and the circle. To avoid this:

- Always draw a small stress element and explicitly label positive normal and shear directions.

- Check that your point on Mohr’s Circle, \( (\sigma_x, \tau_{xy}) \), matches the sign and quadrant implied by your sketch.

- Remember that many textbooks plot positive shear downward on the Mohr’s Circle vertical axis (opposite of a traditional \(x\)-\(y\) plot); follow the convention used in your reference.

If you ever feel unsure, you can fall back on the transformation equations and verify that the circle point you’re using reproduces the same \( (\sigma_{\theta}, \tau_{\theta}) \).

Mohr’s Circle tells you what the stress state is on different planes, not whether that state is acceptable. Once you have the principal stresses and maximum shear stress:

- Use principal stresses as inputs to maximum normal stress or Mohr–Coulomb criteria where appropriate (for brittle materials or soils).

- Combine principal stresses into von Mises equivalent stress if you’re following a ductile failure theory.

- Check both tension and compression limits, as many materials have different allowable values in each direction.

This “Mohr’s Circle first, then failure theory” pattern is a staple in both exam problems and early design passes: the circle provides clean, transformed stresses; the failure criterion tells you what to do with them.

In more advanced work, you might rarely draw Mohr’s Circle explicitly because FEA and software handle the transformations for you. However, understanding the circle remains valuable: it helps you sanity-check output, interpret principal stress plots, and explain why certain orientations are critical in welds, bolts, and composite laminates.

Mohr’s Circle – FAQ

What is Mohr’s Circle in simple terms?

Mohr’s Circle is a graphical tool that shows how normal and shear stresses at a point change as you look at different planes through that point. You plot one circle in \(\sigma\!-\!\tau\) space based on the original stress state, and any point on that circle corresponds to the stresses on some rotated plane in the material. The far right and left points give principal stresses, and the top of the circle gives the maximum in-plane shear stress.

How do you draw Mohr’s Circle step by step?

A common procedure is: (1) draw a \(\sigma\)-axis (horizontal) and \(\tau\)-axis (vertical) with your chosen sign convention; (2) plot the point \((\sigma_x, \tau_{xy})\) and the point \((\sigma_y, -\tau_{xy})\); (3) find the center by averaging the \(\sigma\) coordinates; (4) compute the radius as the distance from the center to either point; (5) sketch the circle with that center and radius; and (6) read off principal stresses where the circle intersects the \(\sigma\)-axis and maximum shear at the top and bottom of the circle. You can then measure angles on the circle (in \(2\theta\)) to find the physical plane orientations.

Do I need Mohr’s Circle if I already know the stress formulas?

You can always use the plane stress transformation equations directly, but Mohr’s Circle provides several advantages. It bundles all possible planes into a single picture, makes it easy to see relative magnitudes and signs of principal and shear stresses, and reduces the chance of algebra mistakes in multi-step problems. Even if you rely on formulas or software in daily work, understanding the circle helps you sanity-check results and interpret principal stress plots correctly.

What is the difference between Mohr’s Circle for stress and for strain?

Mohr’s Circle for strain has the same geometric idea, but you plot normal and shear strains instead of stresses, and the center includes Poisson’s effects depending on how the strain components are defined. The factor-of-two angle relationship still holds, and the circle still yields principal strains and maximum shear strain. In linear elastic materials, principal strains and principal stresses are related through Hooke’s law, so the stress and strain circles are closely linked but not identical.

References & further reading

- Standard mechanics of materials textbooks that introduce plane stress, Mohr’s Circle, and failure criteria (for example, widely used “Mechanics of Materials” texts for civil and mechanical engineering).

- University lecture notes and open courseware on solid mechanics and structural analysis, which provide additional derivations, diagrams, and practice problems using Mohr’s Circle.

- Design manuals and codes of practice for steel and concrete structures, where principal stresses and maximum shear stresses from Mohr’s Circle are used as inputs to code-based checks.