Fluid Mechanics · Navier-Stokes Equation

Navier-Stokes Equation – viscous fluid flow, pressure & inertia explained

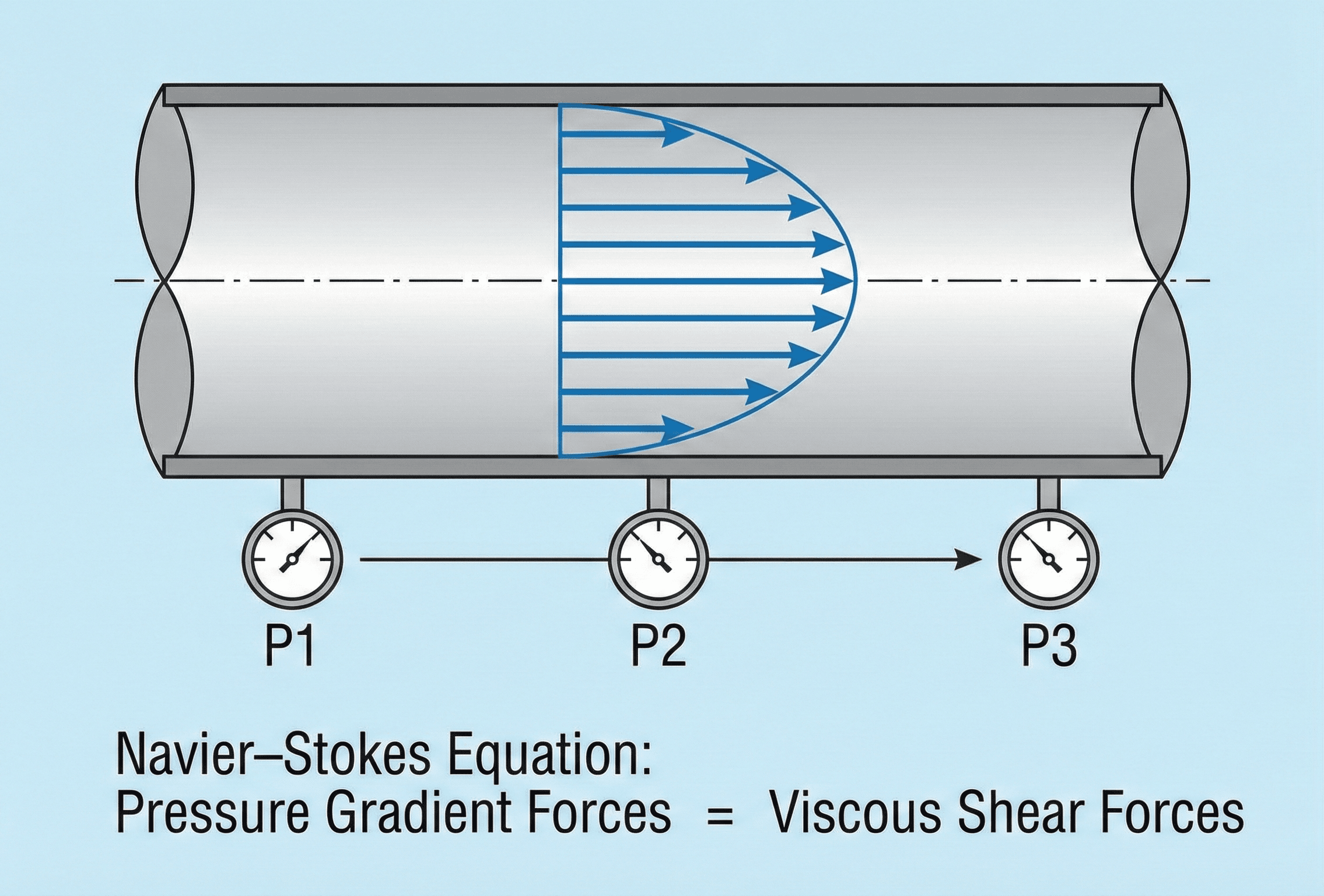

The Navier–Stokes equation is the core momentum balance for real fluids, combining inertia, pressure, viscosity, and body forces into one framework that underpins pipe-flow calculations, aerodynamics, and modern CFD.

Quick answer: what the Navier–Stokes equation tells you

Core vector form (incompressible, Newtonian fluid)

The Navier–Stokes equation says that for a small fluid element, the rate of change of momentum (left-hand side) is exactly balanced by pressure forces, viscous stresses, and body forces like gravity (right-hand side).

At its heart, the Navier–Stokes equation is just Newton’s Second Law applied to a tiny “parcel” of fluid. Instead of a single mass with one velocity, you now have a velocity field \( \vec{u}(x,y,z,t) \) and pressure field \( p(x,y,z,t) \). The time derivative and convective term \( (\vec{u}\cdot\nabla)\vec{u} \) capture how inertia moves fluid momentum around, while the pressure gradient \( -\nabla p \) and viscous diffusion term \( \mu \nabla^2 \vec{u} \) push back and smooth things out.

In most engineering courses and design work, you rarely solve the full 3D, unsteady Navier–Stokes equation directly by hand. Instead, you simplify it using reasonable assumptions (steady flow, one-dimensional variation, symmetry, negligible terms) until it collapses into tractable ODEs or algebraic relationships. Those familiar pipe pressure-drop correlations, fully developed laminar profiles, and boundary-layer formulas all descend from Navier–Stokes with a stack of approximations.

You also pair Navier–Stokes with the continuity equation for incompressible flow, \(\nabla \cdot \vec{u} = 0\), which enforces mass conservation. Together they form the backbone of fluid mechanics. Later in this guide we’ll unpack each symbol in the variables & notation section and walk through realistic worked examples that show how the equation is actually used.

Symbols, units & notation in the Navier–Stokes equation

For an incompressible Newtonian fluid, the Navier–Stokes momentum equation is usually written as \( \rho (\partial \vec{u}/\partial t + (\vec{u}\cdot\nabla)\vec{u}) = -\nabla p + \mu \nabla^2 \vec{u} + \rho \vec{g} \), paired with the continuity constraint \( \nabla \cdot \vec{u} = 0 \). The table below summarizes the main symbols and common engineering units you will see in this formulation.

Core Navier–Stokes notation

| Symbol | Quantity | SI Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( \vec{u} \) | Velocity vector | m/s | Fluid velocity field; often written as components \( \vec{u} = (u, v, w) \) in Cartesian coordinates. Depends on position and time. |

| \( \rho \) | Density | kg/m³ | Mass per unit volume of the fluid. Taken as constant for incompressible flow; may vary in compressible regimes. |

| \( p \) | Static pressure | Pa (N/m²) | Thermodynamic (mechanical) pressure field in the fluid. Its gradient \( \nabla p \) drives flow and balances viscous stress. |

| \( \mu \) | Dynamic viscosity | Pa·s (kg/(m·s)) | Measures internal friction due to velocity gradients. For a Newtonian fluid, shear stress is proportional to the velocity gradient with constant \( \mu \). |

| \( \nu \) | Kinematic viscosity | m²/s | Defined as \( \nu = \mu / \rho \). Convenient in non-dimensional forms and when working with diffusion-like terms \( \nu \nabla^2 \vec{u} \). |

| \( \vec{g} \) | Body force per unit mass | m/s² | Often gravitational acceleration, \( \vec{g} \approx (0, 0, -9.81)~\text{m/s}^2 \). Other body forces (e.g., electromagnetic) can be added similarly. |

| \( \nabla \) | Gradient operator | 1/m | Vector differential operator. Forms \( \nabla p \) (pressure gradient), \( \nabla \cdot \vec{u} \) (divergence), and \( \nabla^2 \vec{u} \) (Laplacian). |

| \( (\vec{u}\cdot\nabla)\vec{u} \) | Convective acceleration | m/s² | Nonlinear transport of momentum by the flow itself. Responsible for many flow instabilities and turbulence behavior. |

| \( \nabla \cdot \vec{u} \) | Divergence of velocity | 1/s | For incompressible flow, \( \nabla \cdot \vec{u} = 0 \) ensures mass conservation by enforcing volume continuity. |

Unit systems & practical notes

- SI is the default for fluids: velocities in m/s, density in kg/m³, viscosity in Pa·s, and pressure in Pa. This keeps all terms in Navier–Stokes dimensionally consistent.

- Imperial / U.S. customary: using ft, lbm, and lbf requires careful use of conversion constants and consistent gravitational factors. Many handbooks tabulate viscosity in centipoise (cP) or lbm/(ft·s); always convert before plugging into equations.

- Steady vs. unsteady: in steady flows, the local time derivative \( \partial \vec{u} / \partial t \) vanishes, but convective terms can still be nonzero and dominate the behavior.

In everyday design, you rarely manipulate every term explicitly. Instead you work with specialized forms (pipe-flow pressure drop, boundary layers, jet impingement) and supporting tools such as Reynolds number, friction-factor, or Bernoulli-based calculators built on top of the Navier–Stokes foundation.

How the Navier–Stokes equation balances inertia, pressure & viscosity

Conceptually, the Navier–Stokes equation is a bookkeeping statement: for each tiny fluid element, the inertial change of momentum must be supplied by forces. What makes it challenging is that every term depends on the same unknowns \( \vec{u} \) and \( p \), and the convective term is nonlinear. Still, the physical interpretation of each piece is straightforward once you look at them one by one.

Left-hand side: local + convective acceleration

The total (or material) acceleration of a fluid particle is the sum of a local term and a convective term:

The first term \( \partial \vec{u} / \partial t \) captures how velocity at a fixed point changes with time (unsteady behavior). The second term \( (\vec{u}\cdot\nabla)\vec{u} \) captures how a particle moving through spatial velocity gradients experiences acceleration even in steady flow (think of speeding up through a nozzle or curving around a bend).

Multiplying by density \( \rho \) gives the inertial force per unit volume, \( \rho D\vec{u}/Dt \), which is what the right-hand side of Navier–Stokes must balance using pressure, viscous, and body-force contributions.

Right-hand side: pressure, viscosity & body forces

On the right-hand side, \( -\nabla p \) represents how spatial pressure differences push the fluid around. Regions of high pressure accelerate fluid toward regions of low pressure. The viscous term, \( \mu \nabla^2 \vec{u} \) (or \( \rho \nu \nabla^2 \vec{u} \)), acts like a diffusion operator on momentum, smoothing out sharp velocity gradients and dissipating energy as heat.

Body forces like gravity, electromagnetic forces, or fictitious forces in rotating frames add additional source terms. In many low-speed liquid flows, gravity primarily appears as a hydrostatic pressure gradient that can be absorbed into a modified pressure variable.

Common simplified forms & the role of Reynolds number

In engineering, you almost always work with simplified Navier–Stokes equations tuned to a specific geometry. For example, fully developed laminar flow in a horizontal pipe reduces to a one-dimensional balance between pressure gradient and viscous shear:

Non-dimensionalizing Navier–Stokes reveals the importance of the Reynolds number, \( \mathrm{Re} = \rho U L / \mu = U L / \nu \), where \(U\) and \(L\) are characteristic velocity and length scales:

When \( \mathrm{Re} \ll 1 \), viscous terms dominate (creeping or Stokes flow). When \( \mathrm{Re} \gg 1 \), inertial terms dominate and flows tend to become turbulent, making direct analytical solutions of Navier–Stokes almost impossible without modeling.

Taken together, Navier–Stokes and continuity form a tightly coupled system of PDEs. For simple geometries and regimes you can still obtain closed-form solutions, but most real design problems rely on correlations, reduced-order models, or CFD codes that discretize these equations and approximate them numerically.

Worked examples using the Navier–Stokes equation

You typically don’t write out the full 3D Navier–Stokes equation in every design calculation. Instead, you simplify it to match a geometry and flow regime and then solve the reduced form. The examples below show how engineers connect Navier–Stokes to familiar results: fully developed laminar pipe flow, Couette flow between plates, and scaling with Reynolds number.

Example 1 – Pressure gradient for laminar flow in a small pipe

Water at \(20^\circ\text{C}\) (density \( \rho \approx 998~\text{kg/m}^3 \), dynamic viscosity \( \mu \approx 1.0 \times 10^{-3}~\text{Pa·s} \)) flows steadily through a long, horizontal circular pipe of radius \( R = 5~\text{mm} \). The volumetric flow rate is \( Q = 1.0 \times 10^{-5}~\text{m}^3/\text{s} \). Assuming fully developed laminar flow, estimate the required pressure gradient \( dp/dx \).

- Use the Hagen–Poiseuille result, derived from Navier–Stokes, for fully developed laminar pipe flow.

- Compute the average velocity from the volumetric flow rate and pipe cross-sectional area.

- Solve for the pressure gradient and interpret the magnitude.

Result: A pressure drop of roughly \(42~\text{Pa}\) per meter is required to maintain this gentle laminar flow. This result is a direct consequence of balancing the viscous term in Navier–Stokes with the axial pressure gradient for fully developed, incompressible, Newtonian flow in a circular pipe.

Example 2 – Simple Couette flow between parallel plates

Consider a Newtonian fluid of viscosity \( \mu = 0.8 \times 10^{-3}~\text{Pa·s} \) between two large parallel plates separated by a distance \( h = 2~\text{mm} \). The bottom plate is stationary, and the top plate moves in the x-direction at \( U = 1.0~\text{m/s} \). Assume steady, incompressible, laminar flow with no pressure gradient. Find the velocity profile \( u(y) \) and the shear stress at each plate.

- Simplify Navier–Stokes for steady, fully developed, unidirectional flow with no pressure gradient.

- Integrate the simplified equation twice and apply no-slip conditions at both plates.

- Determine the shear stress from the velocity gradient at the walls.

Result: The velocity profile is linear from 0 at the bottom plate to \(U = 1~\text{m/s}\) at the top plate, and the shear stress magnitude on each plate is \(0.4~\text{Pa}\). This simple Couette flow is a textbook example where Navier–Stokes collapses to a second-order ODE with a closed-form solution.

Example 3 – Estimating Reynolds number & dominant terms

Air at \(25^\circ\text{C}\) flows through a ventilation duct of characteristic height \( L = 0.3~\text{m} \) with average speed \( U = 5~\text{m/s} \). Take air properties as \( \rho \approx 1.18~\text{kg/m}^3 \) and \( \mu \approx 1.85 \times 10^{-5}~\text{Pa·s} \). Estimate the Reynolds number and comment on which terms in Navier–Stokes are likely to dominate.

- Compute the kinematic viscosity \( \nu = \mu / \rho \).

- Calculate the Reynolds number \( \mathrm{Re} = U L / \nu \).

- Use the magnitude of Re to reason about inertial vs. viscous dominance.

Result: The Reynolds number is on the order of \(10^5\), which is squarely in the turbulent regime for internal flows. In a non-dimensional Navier–Stokes balance, the inertial (convective) terms dominate over viscous terms in the bulk, although viscosity remains critical in the near-wall region where thin boundary layers control friction and pressure drop. Analytical laminar solutions are no longer adequate; instead you rely on empirical correlations or CFD with turbulence modeling.

Design tips, limits & checks when using Navier–Stokes

For many engineers, the Navier–Stokes equation is less a thing you “solve from scratch” and more the governing law that justifies simpler models. Understanding its assumptions and common failure modes helps you choose the right level of fidelity for a given problem and interpret CFD results with a critical eye.

Most practical models are born from selective amnesia: you set certain terms to zero based on regime or symmetry assumptions. Always be explicit about which terms you neglect and verify the regime really supports that choice.

- Steady flow? Then \( \partial \vec{u} / \partial t \approx 0 \), but convective terms may still be large.

- Low Reynolds number? Viscous terms can dominate, leading to Stokes-type flow where inertia is negligible.

- High-speed but nearly inviscid regions? You may retain inertia and pressure but drop viscosity, leading toward Euler equations backed by boundary-layer corrections near walls.

- Ignoring continuity: applying a momentum balance without ensuring \( \nabla \cdot \vec{u} = 0 \) leads to non-physical sources or sinks of mass.

- Using laminar correlations in turbulent regimes based purely on “looks” instead of computing Reynolds number and checking criteria.

- Trusting CFD results without mesh refinement, turbulence-model sensitivity, or basic sanity checks against hand calculations and known limiting cases.

Before investing in detailed models, use simple estimates to judge whether Navier–Stokes simplifications and results are realistic.

- Compute Reynolds number to decide if laminar, transitional, or turbulent modeling is appropriate.

- Estimate pressure drops using standard correlations and compare with any detailed solution to ensure order-of-magnitude agreement.

- Check whether predicted velocities and pressure gradients are compatible with pump curves, fan performance, or structural limits in the system.

When your system pushes into complex regimes—multiphase flow, strong compressibility, combustion, or complex rheology—the classical incompressible Newtonian Navier–Stokes equation needs to be extended or coupled to additional transport equations. The underlying idea, however, remains the same: momentum changes must be balanced by surface and body forces, and those balances are fundamentally local and differential.

Navier–Stokes Equation – FAQ

What is the Navier–Stokes equation in simple terms?

In simple language, the Navier–Stokes equation says that for each tiny chunk of fluid, the way its velocity changes is controlled by three things: pressure differences, viscous friction, and body forces like gravity. It is just Newton’s Second Law written for a fluid instead of a single solid object, but expressed as differential equations in space and time.

Is the Navier–Stokes equation only for incompressible flow?

No. The form most students first see is the incompressible Newtonian version, which assumes constant density and a linear relationship between shear stress and strain rate. More general formulations include density variations, energy equations, and more complex constitutive laws, but they are still often lumped under the “Navier–Stokes” umbrella. For low-speed liquid flows and many air-handling systems, the incompressible assumption is very good.

Why is solving the Navier–Stokes equation so difficult?

Difficulty comes from three sources: the equations are nonlinear due to the convective term, they are coupled in three spatial dimensions plus time, and boundary conditions are often complex. For high Reynolds numbers, small changes in initial or boundary conditions can have large effects (turbulence), making analytical solutions nearly impossible and numerical solutions sensitive to mesh, models, and time stepping. That is why only a handful of idealized flows have closed-form solutions.

Do I always need CFD to use the Navier–Stokes equation in engineering?

Not at all. Many everyday calculations—pipe sizing, simple duct systems, lubrication films, laminar cooling channels—use correlations or simplified forms derived from Navier–Stokes without full CFD. CFD becomes essential when geometry is complex, flows are strongly three-dimensional or unsteady, or when you need detailed local information that correlations cannot provide. Even then, hand calculations based on simplified Navier–Stokes forms remain critical for checking CFD results.

References & further reading

- Standard fluid mechanics textbooks that derive and apply the Navier–Stokes equation, such as widely used university texts on incompressible flow and viscous fluid dynamics.

- Engineering handbooks and design guides for piping, HVAC, turbomachinery, and aerodynamics that show how Navier–Stokes reduces to practical correlations and charts.

- CFD software documentation and best-practice guides explaining turbulence models, mesh quality, and verification & validation strategies grounded in the Navier–Stokes equations.