Mechanical Engineering · Law of Universal Gravitation

Law of Universal Gravitation – gravitational force between masses explained

Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation states that any two masses attract one another with a force proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers, forming the basis for weight, orbits, tides, and many gravity-driven engineering calculations.

Quick answer: what the Law of Universal Gravitation says

Core formula

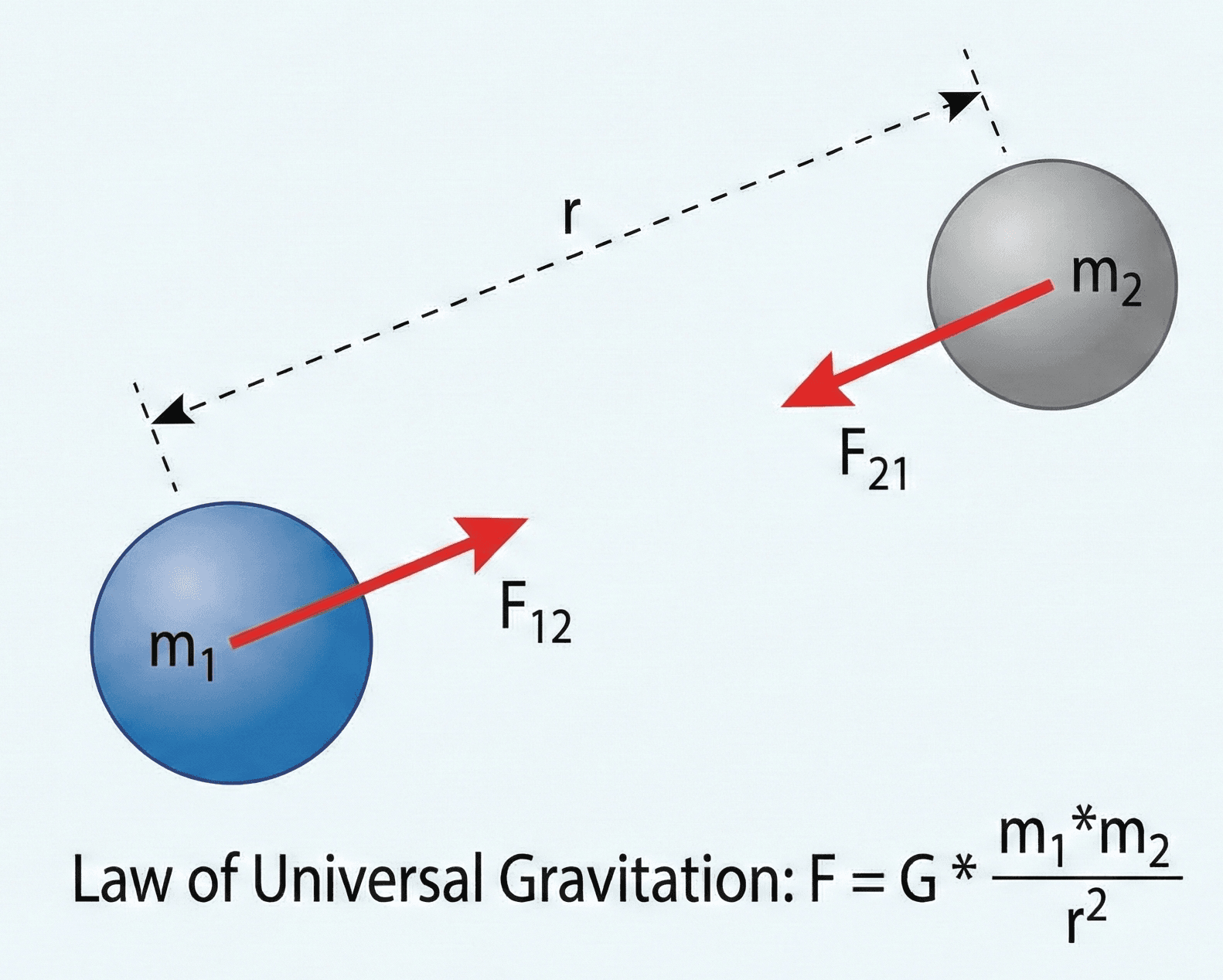

The Law of Universal Gravitation states that any two point masses attract each other with a force \(F\) along the line joining them, proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance \(r\) between their centers, with proportionality constant \(G\) (the gravitational constant).

At an everyday level, this law explains why you have weight: the Earth (mass \(M_{\oplus}\)) pulls on your mass \(m\) with a force \( F = G \dfrac{M_{\oplus} m}{r^2} \), where \(r\) is the distance from Earth’s center. Near the surface, where \(r\) is almost constant, this reduces to the familiar \(F \approx m g\), with \(g \approx 9.81~\text{m/s}^2\). At larger scales, the same inverse-square structure governs planetary orbits, satellite trajectories, and even the way gravity surveys respond to buried density contrasts.

For most engineering calculations, you treat each body as if its entire mass were concentrated at its center of mass and assume Newtonian gravity is accurate enough. As we’ll see in the worked examples, the workflow is usually: identify the two masses, measure or estimate the center-to-center separation, plug into \( F = G \dfrac{m_1 m_2}{r^2} \), then interpret the result as a force or equivalent acceleration.

Symbols, constants & units in the Law of Universal Gravitation

In compact form, the Law of Universal Gravitation is written as \( F = G \dfrac{m_1 m_2}{r^2} \) for the magnitude of the force between two point masses. In vector form, the force on mass \(m_2\) due to mass \(m_1\) points along the line between them and is attractive. The table below summarizes the main symbols and engineering units you will encounter when using this equation.

Common notation for universal gravitation

| Symbol | Quantity | SI unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( F \) | Gravitational force (magnitude) | Newton (N) | Magnitude of the attractive force between two masses \(m_1\) and \(m_2\), acting along the line connecting their centers. |

| \( m_1, m_2 \) | Interacting masses | Kilogram (kg) | Masses of the two bodies. In engineering contexts these are often a planet and a spacecraft, two celestial bodies, or a test mass and source mass in a lab experiment. |

| \( r \) | Center-to-center distance | Meter (m) | Distance between the centers of mass of the two bodies. For spherical bodies of radius \(R_1\) and \(R_2\) with a gap \(h\) between surfaces, \( r = R_1 + R_2 + h \). |

| \( G \) | Gravitational constant | \( \text{N·m}^2/\text{kg}^2 \) | Universal constant setting the strength of gravity: \( G \approx 6.674 \times 10^{-11}~\text{N·m}^2/\text{kg}^2 \). Very small, reflecting how weak gravity is compared with other fundamental forces. |

| \( g \) | Local gravitational acceleration | m/s² | Acceleration due to gravity at a point near a massive body: \( g = G \dfrac{M}{r^2} \). Near Earth’s surface, \( g \approx 9.81~\text{m/s}^2 \). This is sometimes called “little \(g\)” to distinguish it from “big \(G\)”. |

| \( \mu = G M \) | Standard gravitational parameter | \( \text{m}^3/\text{s}^2 \) | Product of \(G\) and a central body’s mass \(M\). Frequently tabulated for planets and stars because it is easier to measure precisely than \(G\) or \(M\) separately. |

Unit systems & practical notes

- SI is the default: use kilograms, meters, and seconds so forces come out in newtons. This keeps \(F = G \dfrac{m_1 m_2}{r^2}\) dimensionally clean.

- Use center-to-center distance: \(r\) goes from the center of one body to the center of the other, not just the separation between surfaces.

- Little \(g\) vs. big \(G\): \(G\) is a universal constant; \(g\) depends on where you are relative to a specific mass distribution.

Once you know the masses and separation, you can plug them into the Law of Universal Gravitation by hand or experiment numerically with the Law of Universal Gravitation calculator to explore how the force changes with mass and distance.

How universal gravitation behaves and why it’s an inverse-square law

The Law of Universal Gravitation tells you that doubling one mass doubles the force, doubling both masses quadruples the force, and doubling the distance reduces the force by a factor of four. This \(1/r^2\) behavior is characteristic of “central” forces that spread out uniformly in three dimensions, like light intensity or electric fields from a point charge. The gravitational interaction acts along the line connecting the two centers and is always attractive.

For spherically symmetric bodies (like idealized planets and stars), the law lets you treat the entire mass as if it were concentrated at the center. That is why you can approximate the Earth–satellite system using only the Earth’s total mass \(M_{\oplus}\), the satellite mass \(m\), and the orbital radius \(r\), rather than integrating over every bit of rock and metal inside the planet.

From force to acceleration: connecting \( F = G \dfrac{m_1 m_2}{r^2} \) to \( g \)

In many engineering problems you care more about acceleration than force. Starting from the Law of Universal Gravitation and Newton’s Second Law, you can derive local gravitational acceleration \(g\) near a spherical body of mass \(M\).

This shows that for a given planet or moon, \(g\) falls off as \(1/r^2\) as you move away from the center. Near the surface, where \(r\) is roughly the planetary radius, \(g\) is nearly constant; higher altitudes (for example, low Earth orbit) see noticeably smaller \(g\) but not zero. This is why satellites are “weightless” only in the sense of free fall, not because gravity disappears.

From gravitational force to orbital motion

For circular orbits, the gravitational force provides the exact centripetal force needed to keep a satellite moving around a central body. Setting the gravitational force equal to the centripetal requirement \( F = m \dfrac{v^2}{r} \) gives a very useful relationship between orbital speed and radius.

Here \( \mu = G M \) is the standard gravitational parameter of the central body. This compact result underpins basic orbital mechanics: lower orbits have higher orbital speed, and the combination of mass and radius determines what orbital periods and velocities are possible. The same inverse-square law also feeds into approximate formulas for escape velocity and transfer orbits, which are crucial in launch and mission design.

For extremely strong fields (near black holes or neutron stars) or when you need ultra-precise predictions (for example, deep space navigation over many years), general relativity replaces Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation with a more complete theory of gravity as spacetime curvature. But for most engineering contexts involving planets, moons, and satellites, the classical inverse-square law is accurate enough that differences from relativity are negligible compared with modeling uncertainties.

Worked examples using the Law of Universal Gravitation

The examples below mirror common homework and design-style questions: calculating your weight from first principles, seeing how gravity weakens with altitude, and estimating forces between a satellite and Earth. The same workflow extends to geophysics, planetary science, and orbit design problems.

Example 1 – Computing the force between Earth and a person

A physics student of mass \( m = 70~\text{kg} \) stands at sea level on Earth. Take Earth’s mass as \( M_{\oplus} = 5.97 \times 10^{24}~\text{kg} \) and Earth’s radius as \( R_{\oplus} = 6.37 \times 10^{6}~\text{m} \). Using \( G = 6.674 \times 10^{-11}~\text{N·m}^2/\text{kg}^2 \), compute the gravitational force between Earth and the student.

- Identify \(m_1, m_2\), and the center-to-center distance \(r\).

- Plug into \( F = G \dfrac{m_1 m_2}{r^2} \).

- Compare the result with the familiar weight \( W = m g \).

Result: The Law of Universal Gravitation predicts a force of about \(686~\text{N}\), which matches the familiar weight \( W = m g \approx 70 \times 9.81 \approx 687~\text{N} \) to within rounding. This confirms that near Earth’s surface, the compact formula \( W = m g \) is just a special case of the more general inverse-square law.

Example 2 – How much weaker is gravity for a satellite in low Earth orbit?

A small satellite orbits at an altitude of \(h = 400~\text{km}\) above Earth’s surface. Using the same Earth parameters as in Example 1, compare the gravitational acceleration \(g_h\) at 400 km altitude to the surface value \(g_0\).

- Write expressions for \(g_0\) and \(g_h\) using \( g = G \dfrac{M}{r^2} \).

- Form the ratio \( \dfrac{g_h}{g_0} \) so that \(G\) and \(M\) cancel out.

- Compute the percentage of surface gravity at this altitude.

Result: At 400 km altitude, gravity is still about \(88.5\%\) of its surface value. Astronauts feel “weightless” in orbit not because gravity vanishes, but because they and their spacecraft are in continuous free fall around Earth.

Example 3 – Gravitational force between a small satellite and Earth

A \(1{,}200~\text{kg}\) satellite is in a circular orbit \( r = 7.00 \times 10^{6}~\text{m} \) from Earth’s center. Using \( M_{\oplus} = 5.97 \times 10^{24}~\text{kg} \) and \( G = 6.674 \times 10^{-11}~\text{N·m}^2/\text{kg}^2 \), compute the gravitational force on the satellite and the corresponding centripetal acceleration.

- Use \( F = G \dfrac{M_{\oplus} m}{r^2} \) to compute the gravitational force.

- Use \( a = \dfrac{F}{m} \) to find the acceleration (which must equal the centripetal acceleration in circular orbit).

- Interpret the result relative to surface gravity \(g_0\).

Result: The satellite experiences a gravitational force of about \(9.8~\text{kN}\), corresponding to an acceleration of roughly \(8.1~\text{m/s}^2\), or about \(83\%\) of surface gravity. That acceleration provides the exact centripetal acceleration needed for its circular orbit at that radius.

Design tips, limits & checks when using universal gravitation

In engineering, you rarely use the Law of Universal Gravitation in isolation. It is combined with dynamics, orbital mechanics, and material limits to design satellites, analyze gravity survey data, or estimate loads in structures influenced by tides and planetary gravity. The following notes highlight common assumptions, pitfalls, and sanity checks.

The classical formula works beautifully when its assumptions are satisfied. Before trusting your result, check that the problem fits the framework.

- Mass distributions are approximately spherically symmetric or can be treated as point masses at their centers.

- The bodies are far enough apart that their finite size, non-spherical shape, and internal structure do not dominate.

- Velocities and gravitational potentials are low enough that relativistic corrections are negligible.

- Using surface-to-surface separation instead of center-to-center distance for \(r\), which can significantly distort forces for compact systems.

- Mixing units (for example, kilometers for distance with meters for radii, or kilograms with metric tons) and forgetting to convert everything to SI before applying the formula.

- Confusing \(G\) with \(g\): plugging \(9.81~\text{m/s}^2\) in place of the gravitational constant will give wildly incorrect forces.

- Ignoring nearby third bodies whose gravity may not be negligible (for example, Moon–Earth–spacecraft interactions in cislunar space).

A few quick checks can tell you whether your numbers are in the right ballpark before you build them into a design or simulation. Many of these are similar in spirit to dimensional analysis.

- Compare computed accelerations with surface gravity: if a satellite only slightly above the surface has an acceleration orders of magnitude below \(g\), re-check your radius and units.

- Verify that the force on each body is equal and opposite; if not, there is an arithmetic or sign error somewhere in your setup.

- Where possible, compare with known values (for example, standard orbital periods, escape velocities, or tabulated \( \mu = G M \) values) to spot inconsistencies.

When your use case stretches beyond the assumptions of Newtonian gravity – for example, GPS satellite corrections, extreme compact objects, or very long-duration trajectories – you still start with the Law of Universal Gravitation but then incorporate perturbations, non-spherical harmonics of the gravity field, or relativistic corrections. For many engineering projects, though, a carefully checked inverse-square model provides more than enough fidelity.

Law of Universal Gravitation – FAQ

What is the Law of Universal Gravitation in simple terms?

In simple language, the Law of Universal Gravitation says that every pair of objects in the universe pulls on each other with gravity. The strength of this pull grows with the masses of the objects and shrinks with the square of the distance between them. If you double the distance, the force drops to one quarter; if you double one object’s mass, the force doubles.

How do you calculate gravitational force between two objects?

To calculate gravitational force, identify the two masses \(m_1\) and \(m_2\), measure the center-to-center distance \(r\) between them, and plug into \( F = G \dfrac{m_1 m_2}{r^2} \) using \( G = 6.674 \times 10^{-11}~\text{N·m}^2/\text{kg}^2 \). Make sure all quantities are in SI units (kilograms and meters) so the result comes out in newtons. In many problems, one mass is a planet or moon and the other is a much smaller satellite or object.

Is \(G\) the same as \(g\) in gravity equations?

No. \(G\) is the universal gravitational constant, the same everywhere in the universe and used in the equation \( F = G \dfrac{m_1 m_2}{r^2} \). It has units of \( \text{N·m}^2/\text{kg}^2 \). The symbol \(g\) usually refers to local gravitational acceleration (for example, \(9.81~\text{m/s}^2\) near Earth’s surface) and depends on the mass and radius of the body you are near: \( g = G \dfrac{M}{r^2} \). Confusing these two quantities is a very common mistake in early gravity calculations.

When does the Law of Universal Gravitation need to be modified or replaced?

The classical inverse-square law works extremely well for most engineering applications involving planets, moons, and satellites. It needs modification when gravitational fields are very strong (near black holes or neutron stars), when velocities approach the speed of light, or when you require very high precision over large distances and long times. In those regimes, Einstein’s general relativity provides a more accurate description, but Newton’s law usually remains an excellent first approximation and a helpful way to build intuition.

References & further reading

- Introductory university physics texts on mechanics and gravity, which derive the Law of Universal Gravitation, relate it to Kepler’s laws, and develop orbital mechanics and gravitational potential energy.

- Classical mechanics and orbital mechanics texts for engineering students, which expand on the use of \( F = G \dfrac{m_1 m_2}{r^2} \) in satellite design, trajectory planning, and space mission analysis.

- Educational resources from major space agencies and observatories, which provide visual explanations, datasets, and mission examples illustrating how the inverse-square law appears in real missions and observations.