Key Takeaways

- Definition: Transportation engineering is the branch of civil engineering that plans, designs, builds, and operates systems that move people and goods safely and efficiently across road, transit, rail, air, and marine networks.

- Application: Transportation engineers work on everything from city streets, freeways, and interchanges to bus rapid transit corridors, rail lines, airports, ports, and multimodal hubs.

- Decisions: They make data-driven decisions about capacity, safety treatments, traffic control, geometric design, and how to balance vehicles with walking, cycling, and transit.

- Career insight: You’ll find transportation engineers in public agencies, consulting firms, contractors, and mobility start-ups, using a mix of engineering judgment, modeling, and field data.

- What you’ll learn: By the end of this guide you will understand what transportation engineering is, the major sub-disciplines, core design concepts, typical workflows, and the skills needed to enter the field.

Table of Contents

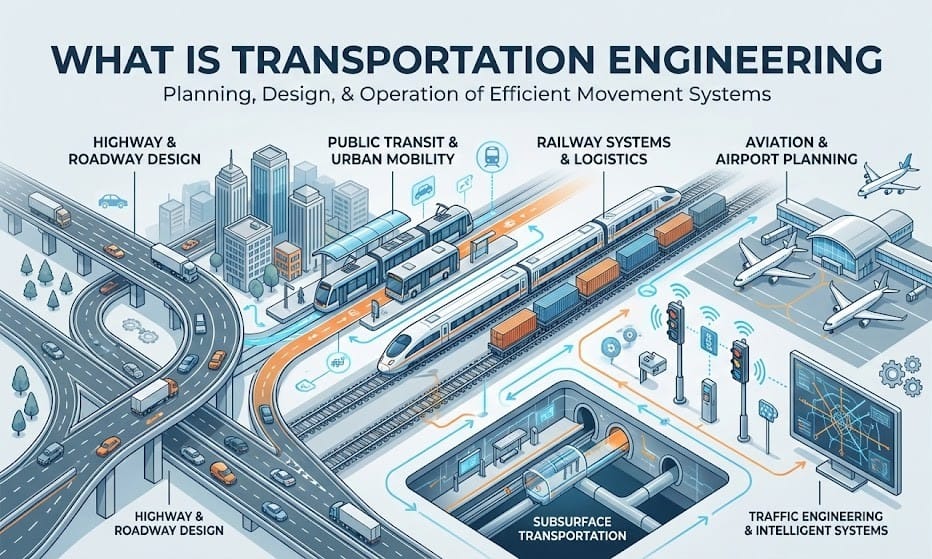

Featured diagram

Introduction

Transportation engineering is the part of civil engineering that keeps cities, regions, and countries moving. It combines geometry, human behavior, and data to design streets, highways, transit lines, railways, bike networks, and freight corridors that are safe, efficient, and resilient. A good transportation system is almost invisible when it works well: buses arrive on time, intersections feel intuitive, crashes are rare, and deliveries show up when expected.

This article answers a simple question—what is transportation engineering?—and then digs into how it fits within civil engineering, the main modes and sub-disciplines, core design concepts like capacity and level of service, common workflows, and the tools and skills transportation engineers use in practice. Whether you are an engineering student, infrastructure enthusiast, or practicing civil engineer, this guide will help you see how the pieces fit together.

What is transportation engineering?

Transportation engineering is the branch of civil engineering focused on planning, designing, operating, and maintaining systems that move people and goods. Those systems include local streets, arterial roads, freeways, intersections, transit corridors, rail lines, airports, seaports, intermodal terminals, and increasingly, bike and pedestrian networks. The goal is to provide safe, reliable, and convenient mobility while minimizing crashes, delays, emissions, and lifecycle costs.

In practical terms, transportation engineers answer questions such as: How many lanes should this corridor have? What type of intersection control—stop signs, signals, or a roundabout—is most appropriate? Where should crosswalks and bike lanes be placed? How should a transit line be routed and spaced? How will a new development affect traffic on the surrounding network? To answer these questions, they combine data, models, design standards, and engineering judgment.

As a student or early-career engineer, you will typically encounter transportation engineering through a survey course that introduces traffic flow, geometric design, and basic planning concepts. From there, you can specialize into traffic operations, transit, pavement design, safety analysis, or freight and logistics, depending on your interests.

How transportation engineering fits within civil engineering

Transportation engineering is one of the core sub-disciplines of civil engineering, alongside structural, geotechnical, water resources, environmental, and construction engineering. Almost every civil project either generates trips or depends on transportation access, so transportation engineers work closely with planners, structural engineers, and geotechnical engineers to make projects feasible and safe.

Connections to other civil sub-disciplines

On a highway project, structural engineers design bridges and retaining walls, geotechnical engineers design foundations and slope stabilization, and water resources engineers design drainage and stormwater systems. Transportation engineers tie those components together by laying out the horizontal and vertical alignment, sight distances, intersection details, and cross-sections so the facility functions as a coherent whole.

In urban environments, transportation engineering overlaps heavily with urban planning and land-use planning. Decisions about density, parking requirements, and street networks directly influence travel demand and mode choice. Modern practice increasingly emphasizes complete streets, Vision Zero safety programs, and sustainable transportation, requiring transportation engineers to think beyond cars and account for transit riders, cyclists, pedestrians, and freight.

Key modes and sub-disciplines in transportation engineering

Transportation engineering covers multiple modes and contexts. Many engineers specialize in one area, but a solid foundation across modes helps you design integrated systems:

Common modes and focus areas

- Roadway and highway engineering: Geometric design of streets, arterials, freeways, interchanges, and intercity highways.

- Traffic engineering: Operations of intersections and corridors, signal timing, capacity analysis, and intelligent transportation systems (ITS).

- Transit and rail: Bus networks, bus rapid transit (BRT), light rail, commuter rail, and subway systems, including station design and right-of-way treatments.

- Active transportation: Walking and bicycling networks, micromobility, shared-use paths, crossings, and accessibility for people with disabilities.

- Freight, airports, and ports: Heavy truck routes, freight rail, terminal layouts, airside and landside airport design, and marine terminals.

| Mode / facility | Primary focus | Example project |

|---|---|---|

| Urban arterial street | Balancing capacity, safety, and multimodal access | Road diet with added bike lanes and transit stops |

| Freeway corridor | Throughput, reliability, incident management | Adding managed lanes and ramp metering |

| Transit corridor | Travel time, reliability, passenger comfort | Designing a new BRT line with signal priority |

| Neighborhood bikeway | Low-stress routes, safety at crossings | Traffic calming and protected bike intersections |

| Freight terminal | Truck and rail access, yard efficiency | Reconfiguring loading docks and access routes |

Core design concepts: capacity, level of service, and safety

Three ideas show up constantly in transportation engineering: capacity, level of service (LOS), and safety. Capacity is the maximum sustainable flow a facility can carry (for example, vehicles per hour per lane). Level of service is a qualitative score, typically labeled A through F, describing the user experience in terms of delay, speed, and comfort. Safety is measured with crash frequencies, severities, and risk metrics, and increasingly with proactive surrogate measures such as conflict rates or exposure.

At a basic level, traffic flow relates volume, speed, and density. A commonly used conceptual relationship is:

where \( q \) is traffic flow (vehicles/hour per lane), \( k \) is density (vehicles/km per lane), and \( v \) is space-mean speed (km/h). As density increases, speeds tend to drop; beyond a critical density, flow also collapses, leading to congestion. Transportation engineers use more advanced models for real design, but this simple relationship is useful for building intuition about how demand, speed, and spacing interact.

- q Flow rate (veh/h/ln). Typical design capacities are on the order of 1,800–2,200 veh/h/ln for freeways under ideal conditions.

- k Density (veh/km/ln). Low densities indicate free-flow regimes; high densities indicate congested or unstable flow.

- v Speed (km/h or mi/h). Design speeds influence alignment, sight distance, stopping distance, and required control devices.

When evaluating a corridor, do not rely on a single LOS grade or volume-to-capacity ratio. Look at the underlying flows, speeds, and crash patterns by time of day and direction. A facility can meet nominal capacity targets while still being unsafe for pedestrians or cyclists.

Worked example: estimating lane volume from speed and density

Example

Suppose you are evaluating a freeway lane during the peak hour. Field observations suggest an average density of \( k = 40 \) vehicles/km/lane and an average speed of \( v = 60 \) km/h. Using the fundamental relationship \( q = k \times v \), the estimated flow is:

A flow of about 2,400 veh/h/ln is higher than the typical practical capacity used in many design manuals (often around 2,000 veh/h/ln for basic freeway segments). That suggests the observed condition is near or beyond stable capacity, and small disturbances may trigger stop-and-go traffic. As a transportation engineer, you might consider operational strategies (like ramp metering or variable speed limits) or geometric changes to improve reliability, rather than simply adding lanes.

Typical transportation engineering workflow

Most transportation projects follow a similar high-level workflow, whether you are designing a local intersection improvement or a regional freeway upgrade. The steps below are often iterative rather than strictly linear.

From problem statement to operations

- Define the problem and goals. Identify existing issues (crashes, delay, reliability, access, equity) and desired outcomes such as safety improvements, travel time savings, or better transit access.

- Collect and analyze data. Gather turning-movement counts, classification counts, speed profiles, origin–destination data, crash histories, land-use and socioeconomic data, and transit ridership, using field equipment and emerging data sources like probe data.

- Develop and screen alternatives. Create a range of geometric and operational alternatives—lane configurations, intersection types, transit treatments, or complete street options—then screen them using high-level performance measures.

- Detailed analysis and design. Apply capacity analysis tools, microsimulation, and geometric design standards to refine promising alternatives. Check sight distance, horizontal and vertical curves, cross slopes, drainage, and accessible facilities.

- Document and coordinate. Prepare plans, profiles, cross-sections, traffic control plans, and reports that clearly communicate the design to reviewers, stakeholders, and contractors.

- Implementation and operations. Support construction, commissioning, and post-implementation monitoring to verify that the project delivers the expected safety and performance outcomes.

Experienced transportation engineers always circle back to the original problem statement and user experience before finalizing a design: does the recommended alternative truly address the safety, mobility, and access needs of all users, or did the team simply optimize for vehicle delay?

Data, tools, and models used by transportation engineers

Modern transportation engineering is highly data-driven. While spreadsheets remain essential, many tasks use specialized software and large datasets. Understanding the categories of tools is more important than memorizing brand names.

Typical data and tool categories

- Traffic and transit data: Tube counts, video analytics, probe data (floating car), transit automatic passenger counts (APC), and automatic vehicle location (AVL).

- Analysis tools: Software implementing the Highway Capacity Manual methods, signal timing optimization tools, microsimulation packages, and queueing/delay models.

- Design and drafting tools: CAD and BIM software for alignments, cross-sections, plans, and profiles, integrated with GIS for spatial context.

- Visualization and communication: Sketching tools, 3D visualization, and web dashboards to help stakeholders understand tradeoffs.

| Tool category | What it helps you do | Typical use case |

|---|---|---|

| Capacity analysis | Estimate LOS, delays, queues | Comparing intersection control options |

| Microsimulation | Model detailed vehicle interactions | Evaluating weaving segments on freeways |

| GIS and mapping | Visualize spatial data and networks | Identifying high-crash corridors and equity gaps |

| CAD/BIM | Produce construction-ready drawings | Final geometric design and contract documents |

| Dashboards | Monitor system performance in near real time | Tracking travel times, incidents, and reliability |

Common pitfalls and good engineering checks

Because transportation projects affect many users and typically have long lifespans, small mistakes can lead to persistent safety issues or expensive retrofits. Being aware of common pitfalls helps you build better designs from the start.

- Designing only for peak hour vehicle flow and ignoring pedestrians, cyclists, and transit riders.

- Using default values in software without verifying that assumptions match local conditions.

- Over-relying on LOS grades while neglecting safety performance or vulnerable road users.

- Misapplying design standards meant for rural highways to constrained urban environments.

- Failing to check units and unit systems (for example, mixing km/h and mi/h or metric and US customary lengths).

A classic mistake is widening a corridor to “solve” congestion without addressing safety or land use. Additional lanes may invite more traffic, create longer crossings for pedestrians, and lock in high speeds, leading to more severe crashes without delivering long-term mobility benefits.

Career paths and skills in transportation engineering

Transportation engineering offers a wide range of career paths. Many engineers start at consulting firms or public agencies and later specialize in planning, design, operations, safety, or emerging areas like mobility data science. Typical employers include city and state departments of transportation, transit agencies, metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs), engineering consultants, contractors, freight and logistics companies, and mobility technology firms.

Core skills for transportation engineers

- Technical foundations: Calculus, statistics, physics, and basic mechanics, plus specialized coursework in traffic engineering, geometric design, and transportation planning.

- Data literacy: Comfort working with spreadsheets, databases, and visualization tools; ability to clean, analyze, and interpret large datasets.

- Software proficiency: Familiarity with CAD, GIS, and at least one capacity analysis or simulation package; scripting or programming skills are a plus.

- Communication and collaboration: Explaining technical results to non-engineers, writing clear reports, and working with planners, architects, and community members.

As you progress, licensure as a Professional Engineer (P.E.) is often required for signing and sealing plans. Many transportation engineers also pursue graduate study or certifications in traffic operations, transportation planning, or road safety to deepen their expertise.

Visualizing transportation engineering

A helpful way to visualize transportation engineering is to picture a multimodal corridor: travel lanes for vehicles, a dedicated bus lane, protected bike lanes, sidewalks, crosswalks, and turn lanes, all coordinated with signals and signs. Every element—from lane widths and signal phasing to curb radii and refuge islands—has been intentionally designed to balance safety, capacity, and accessibility.

In practice, engineers often sketch both plan and cross-section views to communicate how the corridor works. Plan views show how intersections, lanes, and crossings connect along the length of the corridor, while cross-sections reveal how space is divided from building face to building face. Together, these views help stakeholders understand tradeoffs such as reallocating a lane to transit or adding protection for cyclists.

Relevant standards and design references

Transportation engineers rely on a set of well-established manuals and standards to guide design, analysis, and operations. While specific requirements vary by country and agency, the following references are widely used in transportation engineering practice.

- AASHTO Green Book: Provides geometric design guidance for streets and highways, including horizontal and vertical alignment, sight distance, cross-sections, and roadside design. It is often the starting point for roadway and highway design decisions.

- Highway Capacity Manual (HCM): Defines methods for analyzing capacity, level of service, and performance for facilities such as freeways, signalized and unsignalized intersections, roundabouts, and transit corridors.

- Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD): Governs the design and application of signs, signals, markings, and other traffic control devices to ensure consistency and clarity for road users.

- Local and regional design manuals: Many transportation agencies publish their own roadway design manuals, transit design guides, and complete streets policies that supplement national standards and reflect local policy priorities.

Frequently asked questions

Transportation engineering is a rewarding career if you enjoy seeing your work built in the real world and directly influencing how people move every day. It offers steady demand in the public and private sectors, opportunities to specialize in design, planning, safety, or data, and the chance to improve safety, sustainability, and equity in your community.

Transportation engineering is the broader discipline that covers planning, design, and operations for entire networks and all modes, while traffic engineering focuses more narrowly on how vehicles and people move on specific facilities such as intersections, corridors, and freeways, using tools like signal timing, signing, and lane configuration.

You should build a foundation in calculus, statistics, physics, and introductory civil engineering, then take courses in transportation systems, traffic engineering, geometric design, transportation planning, and GIS or data analysis, with optional electives in transit, pavements, or road safety depending on your interests.

Transportation engineers work at city, county, and state transportation departments, transit agencies, metropolitan planning organizations, consulting and design firms, construction companies, and mobility technology firms that develop mapping, routing, and traffic management tools.

Summary and next steps

Transportation engineering is the civil engineering discipline that keeps people and goods moving. It blends geometric design, traffic flow theory, human behavior, and policy to create transportation systems that are safe, efficient, and accessible. From local neighborhood streets to complex freeway interchanges and multimodal hubs, transportation engineers shape how communities grow and function.

In this guide, you explored where transportation engineering sits within civil engineering, the major modes and sub-disciplines, core design concepts like capacity and level of service, a typical project workflow, and the data and tools used in practice. You also saw a simple example of how traffic flow relationships help engineers reason about congestion and performance.

If you are considering this field, the next steps are to strengthen your math and data skills, take dedicated transportation courses, and study real projects in your city. Over time, you’ll develop the judgment needed to balance safety, mobility, cost, and community priorities in your own designs.

Where to go next

Continue your learning path with these curated next steps.

-

Read a deeper dive on traffic flow and capacity concepts

Explore fundamental diagrams, level of service methods, and example calculations for different facility types.

-

See design examples for urban intersections

Walk through step-by-step worked examples comparing stop control, signals, and roundabouts in constrained environments.

-

Explore more transportation engineering resources on Turn2Engineering

Browse guides, equations, and future calculators that build on the concepts introduced on this page.