Fluid Mechanics · Reynolds Number

Reynolds Number – laminar, transitional & turbulent flow explained

Reynolds number is the dimensionless ratio that compares inertial forces to viscous forces in a fluid, telling you whether a flow will be laminar, transitional, or turbulent and which design correlations you can safely use.

Quick answer: what Reynolds number tells you about flow

Core formula

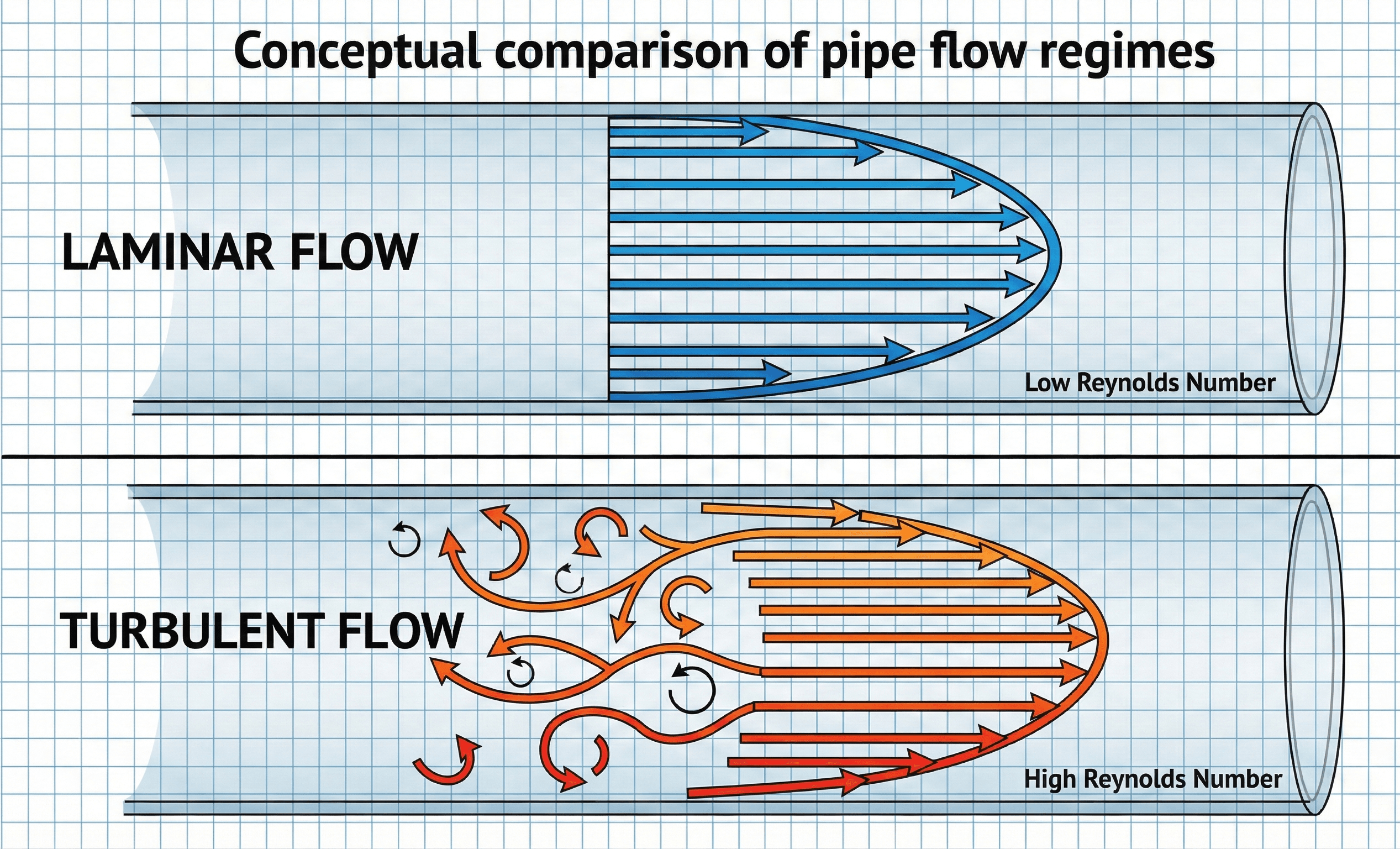

Reynolds number compares inertial forces (\(\rho v^2\)) to viscous forces (\(\mu v / L\)) in a flow; low \(\mathrm{Re}\) means smooth, laminar motion dominated by viscosity, while high \(\mathrm{Re}\) means chaotic, turbulent motion dominated by inertia.

Engineers reach for Reynolds number whenever they need a quick, physics-based sense of “how the flow will behave.” In a circular pipe, for example, flows with \( \mathrm{Re} \lesssim 2{,}300 \) are typically laminar, between \( \mathrm{Re} \approx 2{,}300\) and \(4{,}000\) they are in a sensitive transitional band, and above \( \mathrm{Re} \gtrsim 4{,}000\) they are fully turbulent. Those thresholds change with geometry, but the basic idea – a dimensionless inertia-to-viscosity ratio – is universal.

Because \(\mathrm{Re}\) is dimensionless, you can use it to compare flows that look completely different: air over an aircraft wing, water in a microfluidic channel, oil in a pipeline, or blood in an artery. As we’ll see in the worked examples, once you choose a characteristic velocity and length scale, calculating Reynolds number is straightforward and gives immediate insight into what equations and correlations are safe to use.

Symbols, units & notation for Reynolds number

In fluid mechanics, Reynolds number is usually written as \( \displaystyle \mathrm{Re} = \dfrac{\rho v L}{\mu} \) or \( \displaystyle \mathrm{Re} = \dfrac{v L}{\nu} \). Here \(\rho\) is density, \(v\) is a characteristic velocity, \(L\) is a characteristic length (often a diameter), \(\mu\) is dynamic viscosity, and \(\nu\) is kinematic viscosity. The table below summarizes the most common notation and engineering units.

Common Reynolds number notation

| Symbol | Quantity | Typical SI units | Notes & usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( \mathrm{Re} \) | Reynolds number | – (dimensionless) | Ratio of inertial to viscous forces. Used to classify flow regime and select appropriate correlations for pressure drop, drag, and heat transfer. |

| \( \rho \) | Density | \(\text{kg/m}^3\) | Mass per unit volume. For liquids, often weakly dependent on temperature; for gases, depends strongly on pressure and temperature. |

| \( v \) or \( U \) | Characteristic velocity | \(\text{m/s}\) | Usually the bulk or free-stream velocity. In pipes, often the average velocity \(v = Q / A\). In external flows, the free-stream speed far from the surface. |

| \( L \) | Characteristic length | \(\text{m}\) | Key geometric dimension: diameter \(D\) for circular pipes, hydraulic diameter for ducts, chord length for airfoils, or plate length in boundary-layer flows. |

| \( \mu \) | Dynamic viscosity | \(\text{Pa·s} = \text{kg/(m·s)}\) | Fluid’s resistance to shear. Strong function of temperature; for oils and syrups, small temperature changes can change \(\mu\) by orders of magnitude. |

| \( \nu \) | Kinematic viscosity | \(\text{m}^2/\text{s}\) | Defined by \( \nu = \mu/\rho \). Convenient for liquids and gases when tabulated directly (e.g., water at \(20^\circ\text{C}\) has \(\nu \approx 1.0 \times 10^{-6}~\text{m}^2/\text{s}\)). |

| \( \mathrm{Re}_D \), \( \mathrm{Re}_x \) | Reynolds number based on diameter or distance | – (dimensionless) | Subscripts indicate the chosen length scale: \( \mathrm{Re}_D = \rho v D / \mu \) in pipes, \( \mathrm{Re}_x = \rho U x / \mu \) for boundary layers at distance \(x\) from a leading edge. |

Choosing velocity & length in real problems

- In fully developed pipe flow, use the cross-sectional average velocity, not the local centerline speed.

- For non-circular ducts, use the hydraulic diameter \(D_h = 4A/P\) (area over wetted perimeter) as your characteristic length.

- In external flows, match the length used in your correlation – chord length for lift/drag on airfoils, plate length for flat-plate boundary layers, and so on.

- Always take viscosity at the appropriate film or bulk temperature for the correlation you are using, especially in high-temperature heat exchangers.

Once your symbols and units are clear, you can calculate \(\mathrm{Re}\) by hand or plug values into the Reynolds Number Calculator to quickly explore how fluid, geometry, and velocity changes shift between laminar, transitional, and turbulent regimes.

How Reynolds number compares inertia and viscosity

At its core, Reynolds number is a compact way to express a balance of forces in the Navier–Stokes equations. It tells you whether the “memory” of viscous shear dominates the motion or whether fluid inertia overwhelms viscosity and lets disturbances grow into turbulence. Flows at the same Reynolds number behave similarly, even if they occur in different fluids at different sizes and speeds.

Deriving Reynolds number as a force ratio

A simple back-of-the-envelope derivation starts from characteristic scales. Consider a flow with density \(\rho\), characteristic speed \(v\), and length scale \(L\). A rough inertia force scale is \(F_{\text{inertia}} \sim \rho v^2 L^2\) (think “mass \(\times\) acceleration” over an area), while a viscous shear force scale is \(F_{\text{viscous}} \sim \mu \dfrac{v}{L} L^2 = \mu v L\).

When \(\mathrm{Re} \ll 1\), viscous forces dominate and the flow is “creeping” or Stokesian; inertia is negligible. When \(\mathrm{Re} \gg 1\), inertial effects dominate and the flow tends to be unstable and turbulent. In the intermediate range, both play important roles and the behavior is more sensitive to geometry and disturbances.

Laminar, transitional & turbulent regimes in internal flow

For fully developed flow in a smooth, circular pipe, decades of experiments have produced widely used thresholds. While details vary, a common textbook rule-of-thumb is:

Within the transitional band, small changes in disturbances, pipe roughness, or upstream fittings can flip the flow between laminar-like and turbulent-like behavior. That is why many design correlations either explicitly exclude transitional Reynolds numbers or recommend conservative safety factors in this range. For other geometries, different thresholds apply, but the qualitative picture is similar.

Reynolds number & dynamic similarity between models

Because Reynolds number is dimensionless, matching \(\mathrm{Re}\) between a small-scale model and a full-scale prototype is a key requirement for dynamic similarity. If the model and prototype share the same Reynolds number and similar geometry, their velocity fields, drag coefficients, and pressure distributions become comparable.

In wind tunnels or water channels, you adjust fluid choice, speed, and size to satisfy this equality as closely as possible. When exact matching is impossible, you prioritize matching Reynolds number in the regions that most strongly influence drag, lift, or heat transfer. The design notes & checks later in this guide highlight what to watch for when similarity is imperfect.

Worked examples using Reynolds number

Reynolds number calculations show up everywhere from HVAC ducts to microfluidic chips. The examples below mirror common homework, design, and “back-of-the-envelope” questions: classify flow in a pipe, evaluate external flow over a plate, and see how viscosity changes the regime in an oil pipeline.

Example 1 – Is water flow in a small pipe laminar or turbulent?

Cold water at \(20^\circ\text{C}\) flows through a smooth, horizontal copper pipe of inner diameter \(D = 15~\text{mm}\). The volumetric flow rate is \(Q = 0.0006~\text{m}^3/\text{s}\) (0.6 L/s). Estimate the Reynolds number and determine if the flow is laminar, transitional, or turbulent.

- Compute the cross-sectional area and average velocity in the pipe.

- Look up or recall typical properties of water at \(20^\circ\text{C}\) (density and kinematic viscosity).

- Calculate \(\mathrm{Re}_D = \dfrac{v D}{\nu}\) and compare it to standard pipe-flow thresholds.

Result: The Reynolds number is \(\mathrm{Re}_D \approx 51{,}000\), which is well above the typical turbulent threshold of \(4{,}000\) for pipe flow. The flow is fully turbulent, and you should use turbulent friction-factor and heat-transfer correlations in design.

Example 2 – Boundary layer over a flat plate in air

Air at standard conditions flows at \(U_\infty = 30~\text{m/s}\) over a smooth flat plate with length \(L = 0.8~\text{m}\) in the flow direction. Estimate the Reynolds number at the trailing edge based on plate length, and comment on whether the boundary layer is likely laminar, turbulent, or mixed.

- Use a typical kinematic viscosity for air at room temperature.

- Compute \(\mathrm{Re}_L = \dfrac{U_\infty L}{\nu}\).

- Compare the result to common flat-plate transition criteria.

Result: The Reynolds number based on plate length is \(\mathrm{Re}_L \approx 1.6 \times 10^{6}\). In many external-flow experiments, transition on a smooth flat plate in low free-stream turbulence occurs around \(\mathrm{Re}_x \sim 5 \times 10^{5}\), so most of the downstream boundary layer here is likely turbulent, with a small laminar region near the leading edge and a transition zone in between.

Example 3 – Effect of viscosity in an oil pipeline

A light crude oil at \(40^\circ\text{C}\) flows through a pipeline of inner diameter \(D = 0.25~\text{m}\) with an average velocity of \(v = 1.2~\text{m/s}\). At this temperature, assume the oil has density \(\rho = 820~\text{kg/m}^3\) and dynamic viscosity \(\mu = 0.015~\text{Pa·s}\). Compute \(\mathrm{Re}_D\) and discuss whether you should expect laminar or turbulent flow.

- Compute the kinematic viscosity \(\nu = \mu/\rho\).

- Compute \(\mathrm{Re}_D = \dfrac{v D}{\nu}\).

- Compare to laminar/transitional/turbulent thresholds for pipe flow.

Result: The Reynolds number is \(\mathrm{Re}_D \approx 16{,}000\). This is clearly above the classical turbulent threshold of \(4{,}000\) for pipe flow, so the flow is expected to be turbulent despite the higher viscosity of oil. If the oil were colder (higher \(\mu\)), \(\mathrm{Re}\) would drop, potentially pushing the system toward transitional flow and increasing the sensitivity of pressure-drop predictions.

Design tips, limits & checks when using Reynolds number

In real projects, Reynolds number is rarely the final answer; it is the gatekeeper that tells you which correlations, charts, and CFD assumptions are appropriate. The checks below highlight common pitfalls and how to use \(\mathrm{Re}\) intelligently in design workflows.

Many errors come from mixing up length or velocity definitions. Correlations are calibrated with very specific choices, and changing them silently can break your predictions.

- Match your \(L\) exactly to the correlation (diameter vs. hydraulic diameter vs. chord length vs. plate length).

- Use bulk or average velocity where the correlation expects it; avoid plugging in local peak speeds unless explicitly specified.

- In multi-pass heat exchangers and manifolds, recompute \(\mathrm{Re}\) for each pass if velocities or hydraulic diameters change.

The transitional range is not a crisp on/off switch; it is where small disturbances, surface roughness, and upstream hardware can radically change flow behavior.

- Treat Reynolds numbers between about \(2{,}000\) and \(4{,}000\) in pipes as uncertain territory and avoid operating right on the boundary when possible.

- Expect hysteresis: once a flow turns turbulent, it can stay turbulent even if \(\mathrm{Re}\) drops slightly back toward laminar values.

- Use conservative friction factors or safety factors in transitional regimes, especially in critical systems like process piping or biomedical devices.

While powerful, Reynolds number is not the whole story. Other dimensionless groups and effects can dominate in certain regimes.

- In strongly buoyant flows, the Grashof or Rayleigh numbers can matter more than Reynolds number.

- In compressible high-speed flows, Mach number and compressibility corrections become critical in addition to \(\mathrm{Re}\).

- For non-Newtonian fluids (slurries, polymers, blood), viscosity is not constant; many “effective Reynolds numbers” exist but require care to apply correctly.

As a rule of thumb, use Reynolds number as your first screening tool. If your \(\mathrm{Re}\) is comfortably in a standard laminar or turbulent regime, trusted charts and correlations usually apply. If you are near regime boundaries, dealing with unusual rheology, or coupling multiple effects (heat transfer, phase change, compressibility), that is your signal to dig deeper using more detailed models, experimental data, or high-fidelity simulation rather than relying solely on a single dimensionless group.

Reynolds number – FAQ

What is Reynolds number in simple terms?

In simple language, Reynolds number tells you whether a fluid flow is “smooth” or “chaotic.” Low Reynolds number means viscous forces keep the flow orderly and layered (laminar); high Reynolds number means inertia dominates and the flow tends to break into swirling eddies (turbulent). Mathematically, it is the dimensionless ratio \( \mathrm{Re} = \dfrac{\rho v L}{\mu} \) or \( \mathrm{Re} = \dfrac{v L}{\nu} \).

How do you calculate Reynolds number for pipe flow?

For a circular pipe, Reynolds number is usually based on the internal diameter \(D\) and the average velocity \(v\) in the pipe: \( \displaystyle \mathrm{Re}_D = \dfrac{\rho v D}{\mu} = \dfrac{v D}{\nu} \). You compute the average velocity as \( v = Q/A \), where \(Q\) is the volumetric flow rate and \(A = \pi D^2/4\) is the cross-sectional area. Then you plug in density and viscosity (or kinematic viscosity) at the appropriate fluid temperature.

What Reynolds numbers are laminar and turbulent?

For fully developed flow in a smooth, straight circular pipe, a common rule-of-thumb is: laminar for \( \mathrm{Re}_D \lesssim 2{,}300\), transitional for \(2{,}300 \lesssim \mathrm{Re}_D \lesssim 4{,}000\), and turbulent for \( \mathrm{Re}_D \gtrsim 4{,}000\). Other geometries (annuli, ducts, external flows) have different thresholds, and real systems can trigger turbulence earlier or later depending on roughness and disturbances.

Does Reynolds number depend on pressure, temperature, or fluid type?

Yes, indirectly. Reynolds number depends on density \(\rho\) and viscosity \(\mu\) or \(\nu\), which in turn depend on fluid type, temperature, and (for gases) pressure. For liquids, viscosity is usually the most sensitive property; small temperature changes can significantly change \(\mu\) and therefore \(\mathrm{Re}\). For gases, both density and viscosity vary with temperature and pressure, so it is important to use fluid properties at the actual operating conditions.

References & further reading

- Standard fluid mechanics textbooks covering dimensional analysis, internal and external flows, and Reynolds-number-based regime maps (e.g., undergraduate “Fluid Mechanics” and “Transport Phenomena” texts).

- Experimental studies and handbooks that present friction-factor and heat-transfer correlations as functions of Reynolds number and other dimensionless groups.

- Technical notes and application guides from pump, valve, and heat-exchanger manufacturers that walk through Reynolds-number calculations and regime checks for real industrial fluids.