Mechanical Engineering · Momentum Equation

Momentum Equation – linear momentum, impulse & collisions explained

The momentum equation links an object’s mass and velocity to its “quantity of motion,” giving you a powerful way to analyze impacts, recoil, and collision problems across engineering and physics.

Quick answer: what the momentum equation tells you

Core formula for linear momentum

The momentum equation says that an object’s linear momentum \(p\) equals its mass \(m\) times its velocity \(v\), capturing how hard it is to stop or deflect that object in motion.

Momentum is the bridge between steady motion and sudden impacts. A small object moving very fast and a large object moving slowly can carry similar momentum. The equation \( p = m v \) makes that trade-off explicit: doubling the mass or the speed doubles the momentum. In vector form, \( \vec{p} = m \vec{v} \), so direction matters just as much as magnitude.

In many real problems you do not just care about how much momentum an object has; you care about how that momentum changes. When a net force \(F\) acts over a time interval \(\Delta t\), it produces an impulse \( J = F_{\text{avg}} \Delta t \) that equals the change in momentum:

This impulse-momentum view is especially useful in crashworthiness, ballistics, sports engineering, and any situation where forces act strongly but briefly. We will put this into practice in the worked examples and back up the formulas with clear symbol definitions in the symbols & units section.

Symbols, units & notation in the momentum equation

For linear motion in one dimension, momentum is typically written as \( p = m v \). In full vector form, you will see \( \vec{p} = m \vec{v} \), and for systems of multiple bodies you work with sums of momenta and their changes. The table below summarizes the main symbols and engineering units that appear with the momentum equation.

Common momentum notation

| Symbol | Quantity | SI unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( p \) | Linear momentum (scalar / component) | kg·m/s | Product of mass and velocity magnitude or component along a chosen axis. Often written as \(p_x = m v_x\) in 1D problems. |

| \( \vec{p} \) | Linear momentum (vector) | kg·m/s | Vector quantity whose direction matches the velocity vector. Components are \(p_x\), \(p_y\), \(p_z\). |

| \( m \) | Mass | kg | Measure of inertia. In basic momentum problems, mass is treated as constant for each object. |

| \( v \) | Velocity | m/s | Speed with direction. For one-dimensional motion, you can treat \(v\) as a signed scalar; sign encodes direction. |

| \( J \) | Impulse | N·s or kg·m/s | Time-integral of net force: \( J = \int F \, dt \). Equals the change in momentum \( \Delta p \). |

| \( \Delta p \) | Change in momentum | kg·m/s | Difference between final and initial momentum: \( \Delta p = p_{\text{final}} – p_{\text{initial}} \). Directly tied to impact forces. |

| \( \sum p \) | Total momentum of a system | kg·m/s | Sum of individual momenta for all bodies in the system. Constant in time if external forces along that axis are negligible. |

Unit systems & practical notes

- In SI, momentum naturally comes out in kg·m/s. This is compatible with Newtons and seconds because \(1~\text{N·s} = 1~\text{kg·m/s}\).

- In U.S. customary units, be careful with lbm (pounds-mass), lbf (pounds-force), and slugs. Many “mystery factors” in older references come from fixing momentum and force units to remain consistent with \( F = \frac{dp}{dt} \).

- For collisions along a line, you can treat momentum as signed: choose one direction as positive and let negative velocities and momenta indicate motion in the opposite direction.

Once your variables are defined and units are consistent, it’s straightforward to plug values into the momentum equation by hand or using a dedicated momentum tool when you want to explore “what if” scenarios across different masses and speeds.

How the momentum equation connects mass, velocity & impact

Momentum packages “how much stuff” and “how fast it’s moving” into a single quantity. A freight train moving slowly can have more momentum than a tennis ball fired from a launcher, even though the ball’s speed is much higher. The equation \( p = m v \) captures this balance, and because momentum is a vector, reversing direction flips the sign of \(p\).

From momentum to force: \( F = \dfrac{dp}{dt} \)

The deeper connection between force and momentum comes from Newton’s Second Law in its most general form:

For constant mass, \( \vec{p} = m \vec{v} \) and the derivative simplifies to \( \vec{F}_{\text{net}} = m \dfrac{d\vec{v}}{dt} = m \vec{a} \). But the momentum form is more general and especially useful when forces act over a short time or when mass changes. Integrating both sides over a time interval gives you the impulse–momentum relationship:

In practice, you often approximate the net force as roughly constant during impact and write \( J = F_{\text{avg}} \Delta t = \Delta p \). If you know how far a structure can crush or how long an airbag can extend the stopping time, you can stagger large impact forces into manageable values using this equation.

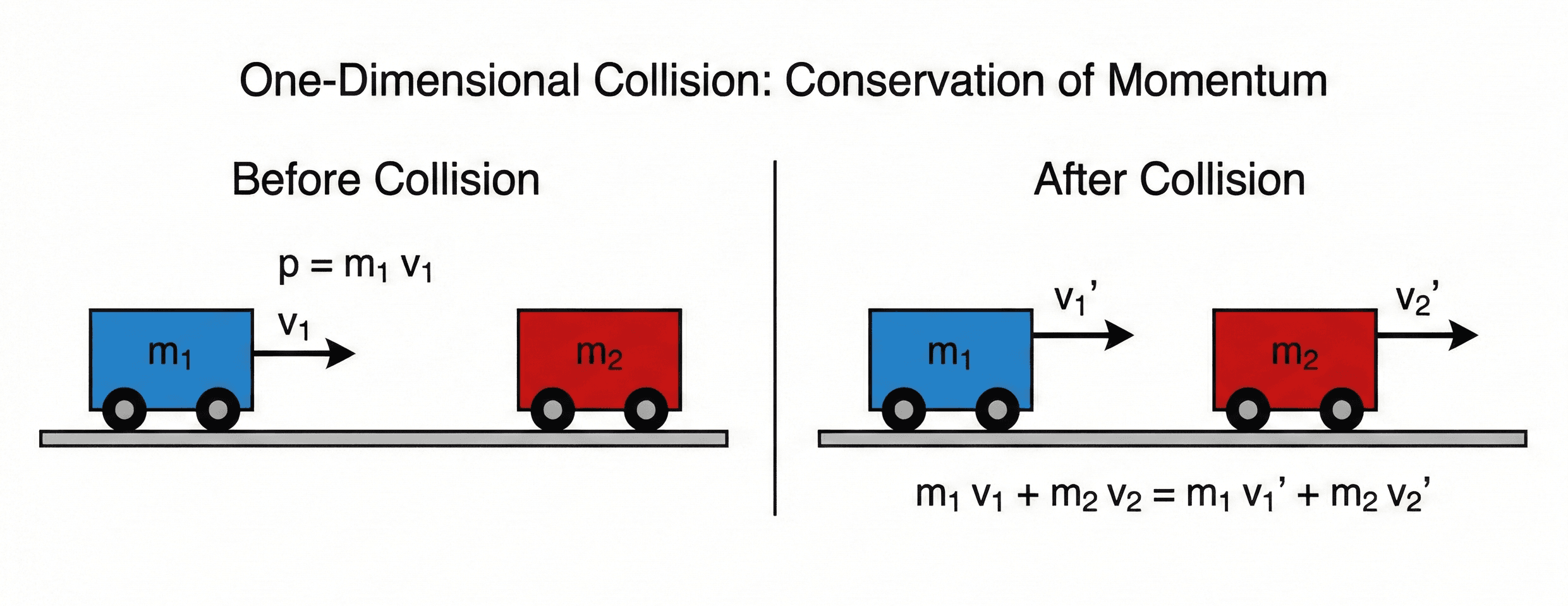

Conservation of momentum in collisions

In a closed system with negligible external forces along a given direction, total momentum along that direction is conserved. For a simple two-body, one-dimensional collision, this becomes:

where \(u_1, u_2\) are initial velocities and \(v_1, v_2\) are final velocities along the line of impact. In a perfectly inelastic collision (the objects stick together), a common variant is:

These conservation equations let you solve for unknown final speeds after impacts, even when details of the force–time profile during the collision are complicated. In real engineering systems, you also check whether assuming “negligible external force” is reasonable over the very short impact time.

Dimensional checks & physical intuition

A quick dimensional check helps catch algebra slips and unit mistakes. The dimensions of momentum are:

If your “momentum” comes out in N or J, you’ve probably mixed up force or energy with momentum. Physically, doubling either mass or speed doubles how difficult it is to stop the motion. That’s why high-speed impacts can be so damaging even for relatively light objects, and why adding mass (for example, in a flywheel) can smooth out fluctuations in rotational speed by increasing stored momentum.

Worked examples with the momentum equation

The examples below match common homework and exam-style questions people search for: calculating momentum directly, using impulse to estimate forces, and applying conservation of momentum to collisions. The same patterns extend to many mechanical and structural applications in practice.

Example 1 – Calculating momentum and change in momentum

A 1,500 kg car is cruising on a straight highway at \(20~\text{m/s}\). The driver accelerates to \(30~\text{m/s}\) to overtake another vehicle. Compute the car’s momentum at each speed and the change in momentum during this maneuver.

- Write the momentum equation \( p = m v \) for initial and final states.

- Substitute the given mass and velocities to find \(p_{\text{initial}}\) and \(p_{\text{final}}\).

- Compute the change in momentum \( \Delta p = p_{\text{final}} – p_{\text{initial}} \).

Result: Increasing speed from \(20\) to \(30~\text{m/s}\) raises the car’s momentum from \(30{,}000\) to \(45{,}000~\text{kg·m/s}\), a change of \(15{,}000~\text{kg·m/s}\). Any braking system or structural element that must arrest the vehicle’s motion needs to be designed with that level of momentum in mind.

Example 2 – Using impulse and momentum to estimate impact force

A 0.40 kg soccer ball moving at \(18~\text{m/s}\) is caught by a goalkeeper and brought to rest in \(0.12~\text{s}\). Assuming the net horizontal force on the ball is roughly constant during the catch, estimate the average force the goalkeeper’s hands exert on the ball.

- Compute the initial and final momentum of the ball.

- Find the change in momentum \( \Delta p \).

- Use the impulse–momentum relation \( F_{\text{avg}} \Delta t = \Delta p \) to solve for \( F_{\text{avg}} \).

Result: The average force exerted by the goalkeeper on the ball is about \(60~\text{N}\) opposite the ball’s direction of motion (the negative sign indicates that it acts to slow the ball). Spreading the catch over a slightly longer time would reduce this average force, which is exactly the idea behind soft padding and “giving” with the impact.

Example 3 – Inelastic collision with conservation of momentum

A 1,000 kg cart rolls along a level track at \(4.0~\text{m/s}\) and collides with a 500 kg cart initially at rest. The carts latch together and move as one unit after impact. Assuming external horizontal forces are negligible during the short collision, find the common velocity immediately after the collision.

- Write conservation of momentum for the system along the track direction.

- Substitute masses and initial velocities to solve for the final velocity \(v_{\text{final}}\).

- Check whether the result seems reasonable based on mass and initial speed.

Result: After the inelastic collision, the two carts move together at about \(2.67~\text{m/s}\). The combined mass is \(50\%\) larger than the original moving cart, so the speed drops to about two-thirds of the original value – exactly what you’d expect from conservation of momentum.

Design tips, limits & checks when using the momentum equation

In engineering, you almost never use the momentum equation in isolation. It sits next to material limits, structural models, and dynamic simulations. Still, a few recurring patterns make momentum-based reasoning especially powerful for first-pass design and quick sanity checks.

For long, steady processes (like a vehicle climbing a hill), it is often more natural to balance forces using \( F = m a \). For short, sharp events such as collisions, impacts, or recoil problems, the momentum form is usually cleaner:

- Use \( p = m v \) and impulse–momentum when forces are large but act over very short times.

- Use conservation of momentum when external forces are small or nearly cancel out over the short impact duration.

- Switch back to force and acceleration when you care about detailed motion between the start and end states, not just before/after snapshots.

- Forgetting that momentum is a vector and treating all velocities as positive even when objects move in opposite directions.

- Assuming momentum is “always conserved” without checking whether external forces are negligible along the axis of interest.

- Mixing units, for example using km/h for velocity with kg for mass and expecting kg·m/s without appropriate conversions.

- Confusing momentum with kinetic energy: both increase with speed, but energy scales with \(v^2\) while momentum scales linearly with \(v\).

Before you commit to a design or draw conclusions from a calculation, do a quick mental check on your momentum results:

- Compare momentum values to familiar benchmarks (for example, typical passenger car highway momentum versus your system).

- Check that your momentum changes are consistent with available stopping distances and allowable forces.

- Ask whether external loads or friction during impact are truly negligible; if not, refine your model rather than relying on a simple conservation argument.

As systems become more complex – multi-body crashes, robotic manipulators with flexible links, or vehicles with significant aerodynamic forces – momentum methods still provide a valuable “first cut.” They help you bound expected speeds, forces, and energy levels before you invest in full finite-element models or high-fidelity multibody simulations.

Momentum equation – FAQ

What is the momentum equation in simple terms?

In simple language, the momentum equation says that an object’s momentum equals its mass times its velocity: \( p = m v \). A heavier object or a faster object has more momentum and is harder to stop or deflect. If you reverse direction, the momentum reverses direction too, because momentum carries the same direction as the velocity.

How do I calculate momentum step by step?

To calculate momentum, first make sure your mass is in kilograms and velocity is in meters per second. Choose a positive direction along the line of motion. Then apply \( p = m v \), including the sign of the velocity. For a system of objects, compute \(p\) for each one and add them to get the total momentum along that direction.

Is momentum always conserved in collisions?

Total momentum is conserved in an isolated system where external forces along the direction you care about are negligible over the short collision time. In many lab-style and exam problems, this is a reasonable approximation. In real engineering systems, external forces like friction, supports, or fluid forces may be significant, so conservation is only approximate unless the impact time is very short or those forces cancel out.

What is the difference between momentum and kinetic energy?

Momentum depends linearly on velocity (\( p = m v \)), while kinetic energy depends on the square of velocity \( \left( E_k = \tfrac{1}{2} m v^2 \right) \). That means doubling speed doubles momentum but quadruples kinetic energy. Momentum conservation is often used to find final velocities after collisions, while energy methods help you understand how much energy is transferred, absorbed, or dissipated as heat, sound, or deformation.

References & further reading

- Standard engineering mechanics and physics textbooks that introduce linear momentum, impulse, and collision analysis alongside Newton’s laws of motion.

- University lecture notes and open courseware on classical mechanics covering momentum, impulse, and conservation principles with derivations and example problems.

- Application notes from automotive, aerospace, and sports equipment manufacturers discussing crashworthiness, impact testing, and energy absorption using momentum-based metrics.