Thermodynamics & Heat Transfer · Planck’s Law

Planck’s Law – blackbody radiation spectrum & photon energy explained

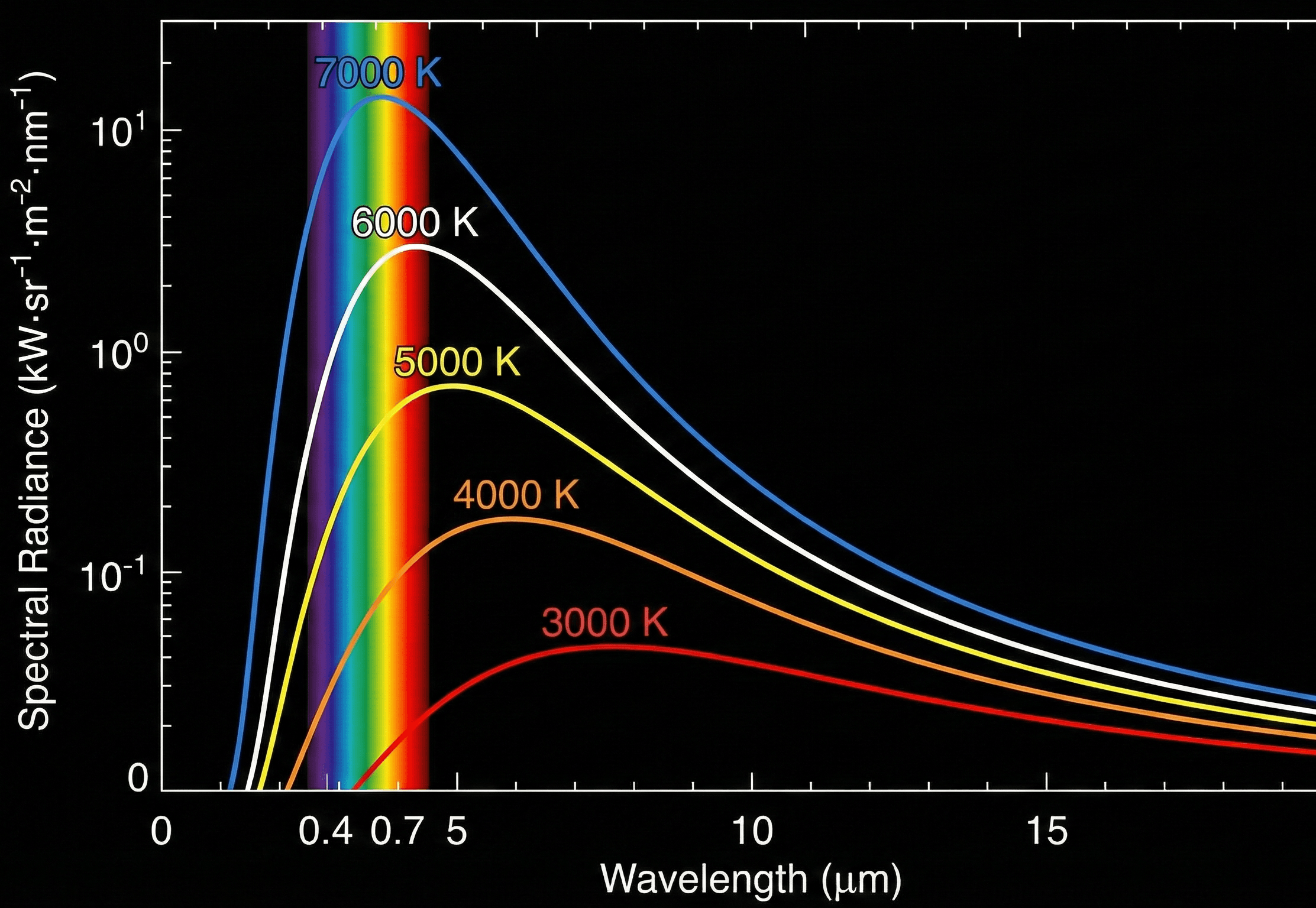

Planck’s Law gives the spectral distribution of blackbody radiation as a function of wavelength and temperature, letting you predict how much thermal energy is emitted at each wavelength for a given temperature.

Quick answer: what Planck’s Law tells you

Core formula (wavelength form)

Planck’s Law gives the spectral radiance \( B_{\lambda} \) of an ideal blackbody at temperature \(T\), telling you how much power per unit area, per unit wavelength, per unit solid angle is emitted at each wavelength \( \lambda \); hotter bodies emit more strongly and their peak shifts to shorter wavelengths.

At an engineering level, Planck’s Law is the starting point for any calculation that cares about the distribution of thermal radiation over wavelength. While the Stefan–Boltzmann Law integrates total blackbody emission over all wavelengths and Wien’s displacement law gives the location of the peak, Planck’s Law gives the full curve: how much radiative power appears near the visible band, in the infrared, or in the ultraviolet for a given temperature.

The law can be written in terms of wavelength \( \lambda \) or frequency \( \nu \). For radiative heat transfer and optical design, the wavelength form is common; for photon-counting and communication systems, the frequency or photon-energy form may be more convenient. Regardless of form, the key idea is that each photon energy level is weighted by the Bose–Einstein statistics of a thermal distribution, which suppresses high-energy photons exponentially.

Symbols, units & notation in Planck’s Law

In wavelength form, Planck’s Law is usually written as \( B_{\lambda}(\lambda, T) = \dfrac{2 h c^{2}}{\lambda^{5}} \dfrac{1}{\exp\!\left(\dfrac{h c}{\lambda k_{\mathrm B} T}\right) – 1} \). In frequency form you’ll see \( B_{\nu}(\nu, T) \) with a different prefactor and exponent. The table below summarizes the main symbols and typical SI units used in engineering practice.

Common notation for the wavelength form

| Symbol | Quantity | Typical SI unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( B_{\lambda} \) | Spectral radiance (per wavelength) | W·m\(^{-3}\)·sr\(^{-1}\) (often W·m\(^{-2}\)·µm\(^{-1}\)·sr\(^{-1}\)) | Radiated power per unit emitting area, per unit wavelength interval, per unit solid angle. Integrating \( B_{\lambda} \) over wavelength and solid angle gives total radiant exitance or intensity. |

| \( \lambda \) | Wavelength | meter (m) (often µm or nm in plots) | Distance between wave crests. In thermal radiation problems, it is common to work in micrometers (µm) for infrared and visible light. |

| \( T \) | Absolute temperature | kelvin (K) | Thermodynamic temperature of the blackbody surface or cavity. Higher \(T\) shifts the spectrum to shorter wavelengths and increases the total radiated power. |

| \( h \) | Planck’s constant | J·s | Fundamental constant linking photon energy to frequency: \( E = h \nu \). Appears in the numerator and exponent of Planck’s Law. |

| \( c \) | Speed of light in vacuum | m/s | Sets the relationship between wavelength and frequency: \( c = \lambda \nu \). Typically taken as \( c \approx 3.00 \times 10^{8}~\text{m/s} \). |

| \( k_{\mathrm B} \) | Boltzmann constant | J/K | Converts between thermal energy and temperature: \( k_{\mathrm B} T \) is the characteristic thermal energy scale for a system in equilibrium at temperature \(T\). |

| \( \nu \) | Frequency (alternate form) | Hz (s\(^{-1}\)) | In frequency form, Planck’s Law uses spectral radiance \( B_{\nu}(\nu, T) \) with units W·m\(^{-2}\)·Hz\(^{-1}\)·sr\(^{-1}\); do not mix \( B_{\lambda} \) and \( B_{\nu} \) without proper conversion. |

Unit systems & practical notes

- In heat-transfer texts, spectral radiance is often plotted as W·m\(^{-2}\)·µm\(^{-1}\)·sr\(^{-1}\); convert µm to m inside the formula and adjust units in post-processing.

- NEVER plug a wavelength in µm directly into the standard SI form without converting to meters – you will be off by powers of 10 in the exponent and prefactor.

- When integrating over a band (for example, 3–5 µm for a thermal camera), make sure the integrand and limits are expressed in the same variable and unit system.

Once the symbols and units are clear, you can sweep temperature, wavelength, or bands numerically using the Planck’s Law calculator to explore spectra without hand-calculating every exponential term.

How Planck’s Law shapes blackbody spectra

Planck’s Law emerged when classical physics failed to explain blackbody radiation. Classical “Rayleigh–Jeans” theory predicted infinite energy at short wavelengths (the ultraviolet catastrophe). Planck resolved this by assuming that electromagnetic energy comes in discrete quanta of size \( h \nu \). When you combine that quantization with thermal equilibrium statistics, you get the Planck distribution.

In the wavelength form, \[ B_{\lambda}(\lambda, T) = \frac{2 h c^{2}}{\lambda^{5}} \frac{1}{\exp\!\left(\dfrac{h c}{\lambda k_{\mathrm B} T}\right) – 1}, \] the prefactor \( \dfrac{2 h c^{2}}{\lambda^{5}} \) grows strongly as wavelength decreases, while the exponential term in the denominator suppresses extremely short wavelengths. The competition between these two factors gives a single, smooth peak in the spectrum at each temperature.

From Planck’s Law to Wien and Stefan–Boltzmann

Two other major radiation laws fall out of Planck’s Law as integrals or optimizations. Taking the derivative of \( B_{\lambda}(\lambda, T) \) with respect to \( \lambda \) and setting it to zero yields Wien’s displacement law:

which tells you where the blackbody spectrum peaks for a given temperature. Integrating \( B_{\lambda} \) over all wavelengths and multiplying by \( \pi \) (for a Lambertian emitter) gives the Stefan–Boltzmann Law:

where \( M(T) \) is the total radiant exitance and \( \sigma \) is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant. In practice, engineers often use these derived laws for quick estimates but return to Planck’s Law when spectral detail matters (for example, choosing IR window materials or filter bands).

Qualitative trends: temperature, wavelength & band fractions

Several important design trends can be read directly from Planck’s Law without solving the integrals in closed form:

- Raising \(T\) increases emission at every wavelength. For a fixed \( \lambda \), both the prefactor and the exponential term shift so that the spectrum grows rapidly with temperature.

- The peak moves to shorter wavelengths with temperature. This gives the familiar shift from red-hot to white-hot as metals heat up and explains why the Sun’s spectrum peaks near visible wavelengths.

- Finite bands capture a fraction of the total power. Integrating \( B_{\lambda} \) over a finite band (say 8–14 µm) gives the band-limited radiant exitance. Designers use these fractions to size detectors and define atmospheric “windows”.

In many engineering workflows, you don’t work with the raw integral by hand. Instead, you rely on tabulated band fractions, numerical integration, or tools based on Planck’s Law to find, for example, “what percentage of a 1000 K blackbody’s energy lies between 0.4 and 0.7 µm?”

Finally, remember that ideal blackbodies are reference models. Real surfaces have emissivity less than 1 and often vary with wavelength. A common engineering approximation is to model real-surface spectral radiance as \( B_{\lambda,\text{real}}(\lambda, T) \approx \varepsilon_{\lambda}(\lambda) B_{\lambda}(\lambda, T) \), where \( \varepsilon_{\lambda} \) is the spectral emissivity. When emissivity is nearly constant over a band, this simplifies many radiative heat-transfer calculations.

Worked examples using Planck’s Law

The examples below mirror common search questions like “How do I calculate blackbody radiance at a given wavelength?”, “How does radiance change with temperature?” and “What fraction of energy lies in a certain band?” The arithmetic here focuses on orders of magnitude and relationships – in practice, you’ll typically let a calculator handle the exponentials.

Example 1 – Spectral radiance at a single wavelength

You want the approximate blackbody spectral radiance at \( \lambda = 1.0~\text{µm} \) for a surface at \( T = 3000~\text{K} \). Use SI units inside Planck’s Law and report \( B_{\lambda} \) in W·m\(^{-3}\)·sr\(^{-1}\). Take \( h = 6.626 \times 10^{-34}~\text{J·s} \), \( c = 3.00 \times 10^{8}~\text{m/s} \), and \( k_{\mathrm B} = 1.381 \times 10^{-23}~\text{J/K} \).

- Convert the wavelength from micrometers to meters.

- Compute the exponent argument \( x = \dfrac{h c}{\lambda k_{\mathrm B} T} \).

- Evaluate the denominator \( \exp(x) – 1 \) and the prefactor \( \dfrac{2 h c^{2}}{\lambda^{5}} \).

- Combine terms to get \( B_{\lambda}(\lambda, T) \).

Result: The blackbody spectral radiance at 1 µm and 3000 K is on the order of \( 10^{12}~\text{W·m}^{-3}\text{·sr}^{-1} \). The exact value will depend on more precise constants, but this illustrates the large magnitudes encountered in thermal radiation calculations.

Example 2 – Comparing radiance at two temperatures

A furnace wall is heated from \( 1000~\text{K} \) to \( 1500~\text{K} \). Roughly how does the spectral radiance at \( \lambda = 3~\text{µm} \) change? We will compare the ratio \( \dfrac{B_{\lambda}(3~\text{µm}, 1500~\text{K})}{B_{\lambda}(3~\text{µm}, 1000~\text{K})} \) using the exponential term, treating the prefactor as only weakly temperature dependent at fixed \( \lambda \).

- Write Planck’s Law ratio at the same wavelength but different temperatures.

- Observe that the \( \lambda^{-5} \) prefactor cancels in the ratio.

- Evaluate the exponent arguments \( x_1 \) and \( x_2 \) for the two temperatures.

- Compute the ratio using the denominator terms.

Result: At 3 µm, increasing the temperature from 1000 K to 1500 K increases the spectral radiance by a factor of roughly 5. In real furnace and burner design, this strong temperature sensitivity means small temperature increases can dramatically raise radiative heat loads on nearby components.

Example 3 – Fraction of power in a finite infrared band (conceptual)

A thermal camera is sensitive in the 8–14 µm band. You are viewing an approximately black surface at \( 600~\text{K} \). Conceptually, how would you estimate what fraction of the total blackbody power lies inside this band?

There is no simple closed-form expression for the band-limited fraction using elementary functions, but Planck’s Law gives a clear computational recipe.

- Write the band-limited radiant exitance as an integral of \( B_{\lambda}(\lambda, T) \) over the band.

- Write the total radiant exitance using the Stefan–Boltzmann Law.

- Form the ratio to get the desired fraction.

- Evaluate the band integral numerically (for example, with a calculator or software).

Result (workflow): To answer questions like “What percentage of a 600 K blackbody’s power lies in 8–14 µm?”, you numerically integrate \( B_{\lambda} \) over that band, convert µm to m within the integral, and divide by \( \sigma T^{4} \). This is precisely the sort of task where a dedicated Planck’s Law or blackbody-band calculator is used in engineering design.

Design tips, limits & checks when using Planck’s Law

In real engineering problems, you rarely have a perfect blackbody and never integrate by hand over the full spectrum. But Planck’s Law remains the underlying physics for thermal imagers, furnace design, solar receivers, and radiative heat-transfer modeling. A few practical patterns help keep your calculations on track.

Planck’s Law assumes an idealized situation that may only be approximately true in the field:

- The emitter behaves as a perfect blackbody (unit emissivity) at a uniform temperature \(T\).

- The radiation is in thermal equilibrium with the walls of the cavity or surface at that temperature.

- Quantum effects enter only through photon statistics; scattering and absorption along the path are handled separately.

When these assumptions are only approximately satisfied, you often introduce a spectral emissivity \( \varepsilon_{\lambda}(\lambda) \) and treat the real spectrum as a scaled version of the blackbody spectrum over the band of interest.

- Mixing frequency- and wavelength-based forms of Planck’s Law without converting correctly between \( B_{\nu} \) and \( B_{\lambda} \).

- Leaving wavelength in µm or nm inside the formula while using SI constants, leading to exponent arguments that are off by orders of magnitude.

- Applying the blackbody spectrum directly to surfaces with strongly wavelength-dependent emissivity (for example, polished metals) without including emissivity models.

- Confusing spectral radiance (per unit area and solid angle) with irradiance or exitance, which already integrate over angles.

Simple checks can catch many implementation errors when using Planck’s Law in spreadsheets, scripts, or calculators:

- Verify that integrating over all wavelengths recovers a total power close to \( \sigma T^{4} \) for a black surface.

- Plot the spectrum for a few temperatures; the peak should shift according to Wien’s law and the total area should grow with \( T^{4} \).

- Check limiting behavior: for very long wavelengths at moderate temperature, the Rayleigh–Jeans approximation should match your numerical result; for very short wavelengths, the radiance should drop rapidly.

When your design involves narrow bands, complex emissivities, or radiative exchange between multiple surfaces (for example, in high-temperature furnaces or spacecraft thermal control), Planck’s Law remains the core spectral model, but you typically wrap it inside more advanced software or finite-element tools that handle geometry, view factors, and participating media.

Planck’s Law – FAQ

What is Planck’s Law in simple terms?

Planck’s Law tells you how bright an ideal “perfectly black” object is at each wavelength for a given temperature. Instead of just saying “hotter objects emit more energy”, it gives the full curve of radiation versus wavelength, showing where the emission peaks and how strong it is in the infrared, visible, or ultraviolet.

What is the formula for Planck’s Law?

In wavelength form, Planck’s Law is \[ B_{\lambda}(\lambda, T) = \frac{2 h c^{2}}{\lambda^{5}} \frac{1}{\exp\!\left(\dfrac{h c}{\lambda k_{\mathrm B} T}\right) – 1}, \] where \( B_{\lambda} \) is spectral radiance, \( \lambda \) is wavelength, \( T \) is absolute temperature, and \( h \), \( c \), \( k_{\mathrm B} \) are physical constants. There is also a frequency-based version \( B_{\nu}(\nu, T) \), which uses frequency \( \nu \) instead of wavelength.

How do you use Planck’s Law to calculate blackbody radiation?

The typical workflow is: (1) choose whether you are working in wavelength or frequency; (2) convert all inputs to consistent SI units; (3) plug \( \lambda \) (or \( \nu \)) and \( T \) into Planck’s formula to get spectral radiance; and (4) if you need total power in a band, numerically integrate over that wavelength or frequency range. In engineering, you often automate steps 3–4 with a calculator or script rather than doing every exponential and integral by hand.

How is Planck’s Law different from Wien’s and Stefan–Boltzmann laws?

Planck’s Law is the most detailed of the three: it gives the entire spectral curve. Wien’s displacement law is derived from Planck’s Law by finding the maximum of that curve, giving a simple relation \( \lambda_{\text{max}} T = \text{constant} \). The Stefan–Boltzmann Law comes from integrating Planck’s spectrum over all wavelengths, yielding the total emitted power proportional to \( T^{4} \). In other words, Wien and Stefan–Boltzmann are summaries; Planck’s Law is the full underlying distribution.

Can I apply Planck’s Law directly to real surfaces?

Real surfaces are rarely perfect blackbodies. To approximate them, engineers often introduce an emissivity factor and write \( B_{\lambda,\text{real}}(\lambda, T) \approx \varepsilon_{\lambda}(\lambda) B_{\lambda}(\lambda, T) \). If emissivity is roughly constant over your wavelength band, a single emissivity value works well; if it varies strongly, you need spectral emissivity data to get accurate results, especially for polished metals, selective coatings, and multilayer optical stacks.

References & further reading

- Standard heat-transfer and radiation texts covering blackbody radiation, Planck’s Law, Wien’s displacement law, and the Stefan–Boltzmann Law, including band calculations and emissivity models.

- University lecture notes and open courseware on thermal radiation and quantum foundations that derive Planck’s Law from photon statistics and compare it to classical predictions.

- Manufacturer application notes for thermal cameras, pyrometers, and IR sensors that show how Planck-based models are used to interpret measured signals and calibrate instruments.