Mechanical Engineering · Potential Energy Equation

Potential Energy Equation – height, gravity & stored energy explained

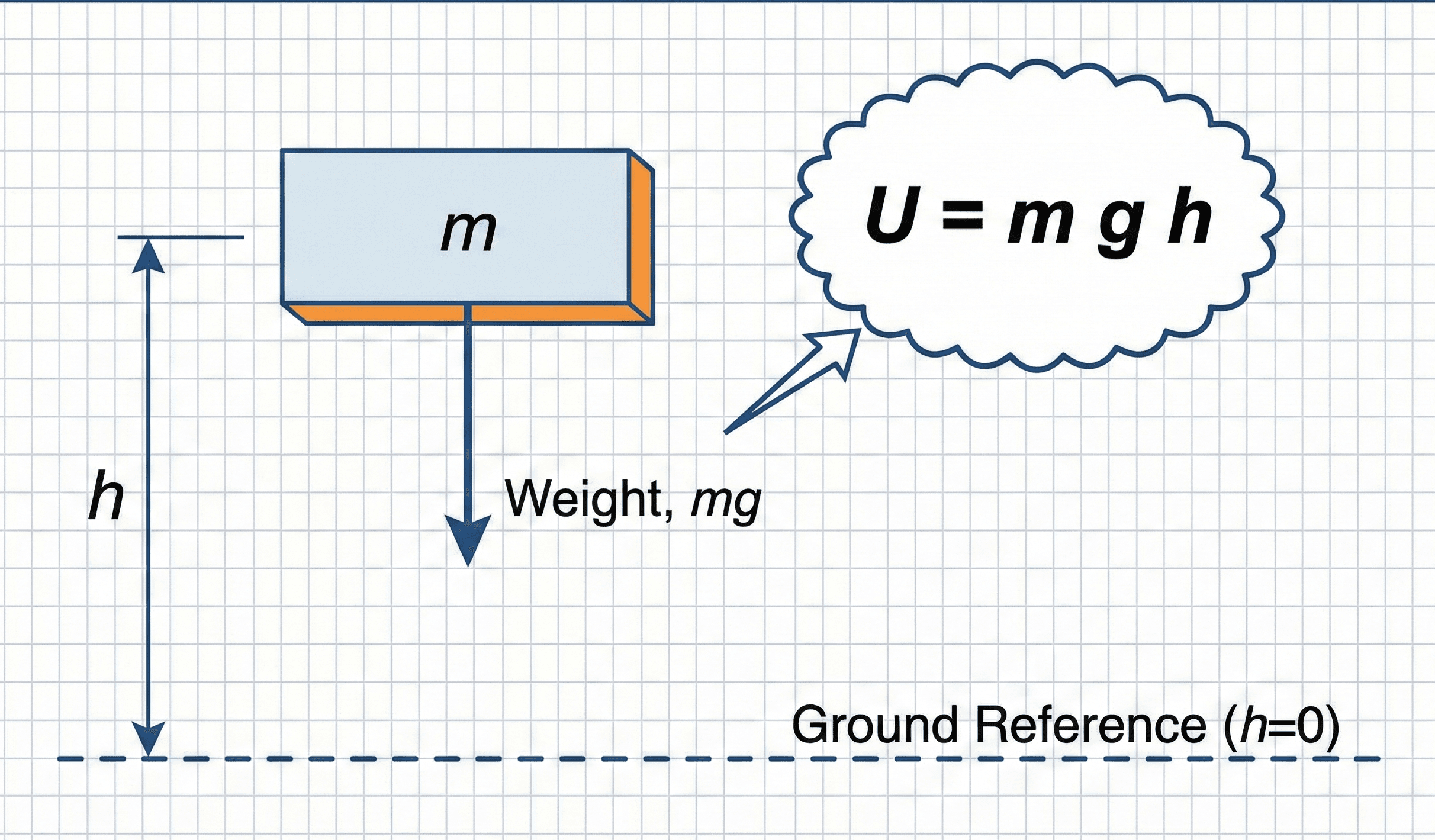

The potential energy equation \( U = m g h \) tells you how much gravitational energy is stored when you lift a mass in a gravitational field, and how much energy can be released as it falls.

Quick answer: what the potential energy equation tells you

Core formula near Earth’s surface

The potential energy equation \( U = m g h \) says that the gravitational potential energy stored in an object is proportional to its mass \(m\), the gravitational field strength \(g\), and its height \(h\) above a chosen reference level.

In practical engineering terms, \( U = m g h \) is the “energy balance” counterpart to Newton’s Second Law. Instead of tracking forces and accelerations at every instant, you track how much energy is stored or released when a mass moves up or down in a gravitational field. If an object rises by a height \(h\), its potential energy increases by \( \Delta U = m g h \). When it falls by the same amount, that energy is typically converted into kinetic energy, heat, deformation, or some useful work done on a machine.

A key idea is that only changes in potential energy matter physically. You are free to set \( U = 0 \) at any convenient reference level: the floor, the ground, the bottom of a shaft, or the lowest point of a ride. What matters in calculations is the difference between two heights, which is why you’ll usually see the equation written as \( \Delta U = m g \Delta h \). As you’ll see in the worked examples, this makes it straightforward to analyze everything from dropped tools to pumped-storage power plants.

Although engineers use many forms of potential energy (elastic, electric, chemical, etc.), the gravitational form \( U = m g h \) is the gateway equation you meet first. It captures the stored energy associated with position in a uniform gravitational field, which is an excellent approximation for most everyday engineering heights near the Earth’s surface.

Symbols, units & notation for \( U = m g h \)

In introductory mechanics and many engineering courses, gravitational potential energy near Earth’s surface is modeled as \( U = m g h \), where the height \(h\) is measured relative to a chosen zero level. You may also see \(PE\) or \(E_p\) used instead of \(U\). The table below summarizes the usual symbols and engineering units.

Common notation and units

| Symbol | Quantity | SI unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( U \) or \( PE \) | Gravitational potential energy | Joule (J) | Energy stored in the mass–Earth system due to height above a reference level. \( 1~\text{J} = 1~\text{kg·m}^2\text{/s}^2 \). |

| \( m \) | Mass | Kilogram (kg) | Inertial mass of the object being lifted or lowered. Often a single body (like a crate), but can represent the total mass of a tank, vehicle, or platform. |

| \( g \) | Gravitational acceleration | m/s² | Magnitude of the local gravitational field. Near Earth’s surface, \( g \approx 9.81~\text{m/s}^2 \); many quick estimates round this to \(10~\text{m/s}^2\). |

| \( h \) | Height | Meter (m) | Vertical distance from a chosen reference level to the object. Only differences in height, \( \Delta h \), affect changes in potential energy. |

| \( \Delta U \) | Change in potential energy | Joule (J) | Difference between two energy states, \( \Delta U = U_2 – U_1 = m g \Delta h \). This is what appears most directly in energy conservation equations. |

Zero level choice & alternate unit systems

- Choose any convenient zero: often the floor, ground, lowest point of motion, or reservoir outlet. Only changes \( \Delta U \) matter, not the absolute value.

- Consistent sign convention: if you define positive \(h\) upwards, then lifting a mass (increasing \(h\)) makes \(U\) larger; lowering it makes \(U\) smaller.

- Other unit systems: in U.S. customary units you’ll typically use mass in slugs, \(g \approx 32.2~\text{ft/s}^2\), height in feet, and energy in ft·lbf. Keep unit conversions tight.

Once you are comfortable with the symbols and units, you can quickly explore different masses and heights using the Potential Energy Calculator to see how \( U = m g h \) scales across everyday and engineering scenarios.

How the potential energy equation comes from work and gravity

Gravitational potential energy is defined in terms of the work done by the gravitational force. For a constant gravitational field near Earth’s surface, the weight of an object is \( W = m g \) downward. If you lift that object slowly upward by a height \(h\), you do positive work against gravity, and gravity does an equal amount of negative work.

From work done by gravity to \( U = m g h \)

Suppose you move a mass \(m\) vertically from height \(h_1\) to height \(h_2\) at constant speed, so kinetic energy doesn’t change. The work done by gravity is

If you choose the reference level such that \( U_1 = 0 \) at \( h_1 = 0 \), then

This is the familiar potential energy equation: energy stored is proportional to height above the reference. Importantly, this derivation assumes a uniform gravitational field and vertical motion; for large height changes or celestial mechanics you must use a more general expression, but \( U = m g h \) is excellent for buildings, cranes, test rigs, and most terrestrial designs.

Energy conservation: trading potential energy for kinetic energy

The real power of the potential energy equation shows up when you combine it with kinetic energy \( K = \tfrac{1}{2} m v^2 \) and conservation of mechanical energy. Neglecting losses like friction and drag, the total mechanical energy

stays constant as an object moves. If an object falls from a height \(h\) and starts from rest, the drop in potential energy becomes kinetic energy:

This single relationship answers many “how fast will it be going?” questions that people search for, from dropped tools on a jobsite to roller-coaster hills and free-fall ride design. Later, you can add losses and safety factors on top of this ideal baseline.

Scaling and dimensional checks

A quick dimensional check confirms the equation is internally consistent. In SI units,

The equation also has intuitive scaling: doubling the mass doubles the stored potential energy; doubling the height does the same. That is why heavy components at high elevations (like tanks on towers or large HVAC units on roofs) are key contributors to both available energy and risk if they fall. When you are designing with this equation, estimates like “roughly 10 J per kilogram per meter” are handy for sanity checks.

Beyond gravity, the broader idea of potential energy extends to springs, electric fields, molecular bonds, and more, each with its own equation (for example, \( U_{\text{spring}} = \tfrac{1}{2} k x^2 \)). But all of these share the same underlying theme as the gravitational case: energy can be stored in a configuration, then transformed into motion, heat, or other forms as the system moves toward a lower potential energy state.

Worked examples using the potential energy equation

These examples mirror common real-world questions: how much energy is stored when lifting a load, how high an object will rise or fall for a given energy change, and how potential energy fits into system-level energy balances. You can adapt the same steps to more complex situations like hoists, winches, and pumped-storage facilities.

Example 1 – Lifting a toolbox onto a workbench

A 12 kg toolbox is lifted from the floor onto a workbench that is 0.9 m high. Take \( g = 9.81~\text{m/s}^2 \). How much gravitational potential energy does the toolbox gain relative to the floor?

- Identify the mass, gravitational acceleration, and change in height.

- Apply \( \Delta U = m g \Delta h \) using the floor as \(U = 0\).

- Interpret the result as “energy stored” in the elevated toolbox.

Result: The toolbox gains about \(1.1 \times 10^2~\text{J}\) of gravitational potential energy. In other words, the person lifting the toolbox has done roughly 106 J of mechanical work against gravity, which is now stored and could be released if the toolbox falls.

Example 2 – How high will a dropped weight accelerate a small object?

A 25 kg counterweight is raised 2.5 m above the floor and attached by a rope over a pulley to a 5 kg package resting on a nearly frictionless horizontal surface. When the system is released, the counterweight falls and accelerates the package. Assuming the rope and pulley are massless and frictionless, how much potential energy is initially stored, and what is the package speed just before the counterweight hits the floor?

- Compute the initial potential energy of the counterweight using \( U = m g h \).

- Assume all of this energy converts into kinetic energy of the 25 kg + 5 kg masses.

- Set \( U_{\text{initial}} = K_{\text{final}} \) and solve for the speed.

Result: The system initially stores about \(6.1 \times 10^2~\text{J}\) of gravitational potential energy, which is converted into kinetic energy as the counterweight falls. Just before impact, both the counterweight and the package move at roughly \(6.4~\text{m/s}\). In a real design, you’d reduce this using friction, dampers, brakes, or control systems.

Example 3 – Estimating energy stored in an elevated water tank

A small community water tower holds \(75{,}000~\text{L}\) of water in a tank whose center of mass is 25 m above ground level. Estimate the gravitational potential energy stored relative to the ground and express it in kilowatt-hours (kWh), a unit more familiar in power and energy billing.

- Convert the water volume to mass using \( 1~\text{L} \approx 1~\text{kg} \) for water.

- Apply \( U = m g h \) with \( h = 25~\text{m} \).

- Convert joules to kWh using \(1~\text{kWh} = 3.6 \times 10^6~\text{J}\).

Result: The elevated water in this tower stores on the order of \(1.8 \times 10^7~\text{J}\), or about 5 kWh of gravitational potential energy. That’s comparable to running a 1 kW pump or heater for around 5 hours. In larger civil or renewable energy projects, these numbers quickly grow into the MWh range.

Design tips, limits & checks for the potential energy equation

In day-to-day engineering work, the potential energy equation is used for everything from rough safety checks to preliminary sizing of storage, lifting, and fall-protection systems. Here are some patterns, assumptions, and pitfalls to keep in mind when you apply \( U = m g h \).

The textbook equation is very reliable within its domain, but that domain has boundaries. Before trusting your numbers, make sure these assumptions are reasonable:

- Height changes are small compared with Earth’s radius, so \(g\) can be treated as constant.

- The gravitational field is uniform over the region you care about (true for most building- and machine-scale problems).

- Energy losses from friction, air drag, and deformation are handled separately (for example with efficiency factors or pressure-drop calculations).

- The mass is concentrated enough that you can treat it as located at a single height (or at a well-defined center of mass).

- Using weight (in newtons) where mass (in kilograms) belongs, or vice versa. Remember: \( W = m g \) and \( U = m g h \); do not plug “20 N” directly in for \(m\).

- Forgetting that only changes in potential energy matter. Shifting your zero level adds a constant to \(U\) but does not change \( \Delta U \) or any physical result.

- Inconsistent sign conventions when combining with other equations, such as taking “downward” as positive in a force balance but “upward” as positive in your energy diagram.

- Mixing SI and U.S. customary units (for example, kg with ft and lbf) without proper conversion, leading to errors by factors of 3.28 or 9.81.

A few quick checks can catch most unreasonable answers before they make it into a report or design document:

- Use the “10 J per kg per meter” rule: at \( g \approx 10~\text{m/s}^2 \), each kilogram raised 1 m stores about 10 J of energy. Scale from there.

- Compare potential energy to kinetic energy: if a computed speed from \( m g h = \tfrac{1}{2} m v^2 \) looks absurdly high, recheck both your heights and units.

- For safety-critical systems (lifts, cranes, fall arrest, high tanks), compute not just the stored energy but what happens if it is suddenly released.

- When working with fluids, it’s often convenient to express potential energy per unit weight as “head” in meters; this is the same physics, just normalized for hydraulic calculations.

In more advanced designs and simulations, you may move beyond the simple \( U = m g h \) form to potential energy functions \( U(y) \) that vary with position or include multiple energy terms (gravitational, elastic, electric). The same logic still applies: you track how the total potential energy changes as the system moves, and use that to understand what motions, speeds, or forces are possible.

Potential energy equation – FAQ

What is the potential energy equation in simple terms?

In simple language, the potential energy equation \( U = m g h \) says: the heavier an object is and the higher you lift it, the more gravitational energy it stores. The constant \(g\) tells you how strong gravity is where you are.

How do I calculate potential energy step by step?

First, choose a reference level where you define \( U = 0 \) (for example, the floor). Next, measure the object’s mass \(m\) and its height \(h\) above that level in meters. Take \( g \approx 9.81~\text{m/s}^2 \) and compute \( U = m g h \). The result is in joules. If the object moves between two heights, use \( \Delta U = m g (h_2 – h_1) \) to find the change in energy.

Does potential energy depend on the path taken?

No. For gravity (treated as a conservative force), potential energy depends only on the starting and ending heights, not the path between them. Lifting a toolbox straight up or along a ramp to the same final height leads to the same change in potential energy \( \Delta U = m g \Delta h \), even though the path lengths and forces along the way differ.

What is the difference between potential energy and kinetic energy?

Potential energy is stored energy due to configuration or position (for example, height in a gravitational field). Kinetic energy is energy of motion, given by \( K = \tfrac{1}{2} m v^2 \). In many problems, potential energy is converted into kinetic energy and back again, while the total mechanical energy stays approximately constant if losses are small.

When is \( U = m g h \) not accurate?

The equation assumes a uniform gravitational field and relatively small height changes compared with Earth’s radius. For satellites, high-altitude trajectories, or planetary-scale problems, you must use the more general gravitational potential energy expression based on Newton’s law of gravitation. In those regimes, \(g\) varies with distance, so a constant \(g\) model is no longer adequate.

References & further reading

- Standard university-level physics and engineering mechanics textbooks covering work, energy, and gravitational potential energy, including derivations of \( U = m g h \) and energy conservation examples.

- Introductory open-course materials on potential energy and conservative forces, which discuss how potential energy is defined in terms of work and how different forms of potential energy arise in mechanics and fields.

- Online tutorials and practice problem sets on gravitational potential energy and energy conservation, useful for building intuition and checking your understanding before design or exam work.