Key Takeaways

- What it is: Transportation modeling uses mathematical and computational models to represent travel demand and network performance so engineers can test “what if?” scenarios before construction.

- How it works: Most planning models follow a structured workflow, from estimating trips and destinations to choosing modes and assigning traffic to specific routes.

- Why it matters: Good models help size infrastructure, estimate congestion and emissions, evaluate designs, and compare alternatives under consistent assumptions.

- Where you’ll use it: From corridor studies and highway design to transit planning and long-range regional plans, modeling is a core skill in Transportation Engineering.

Table of Contents

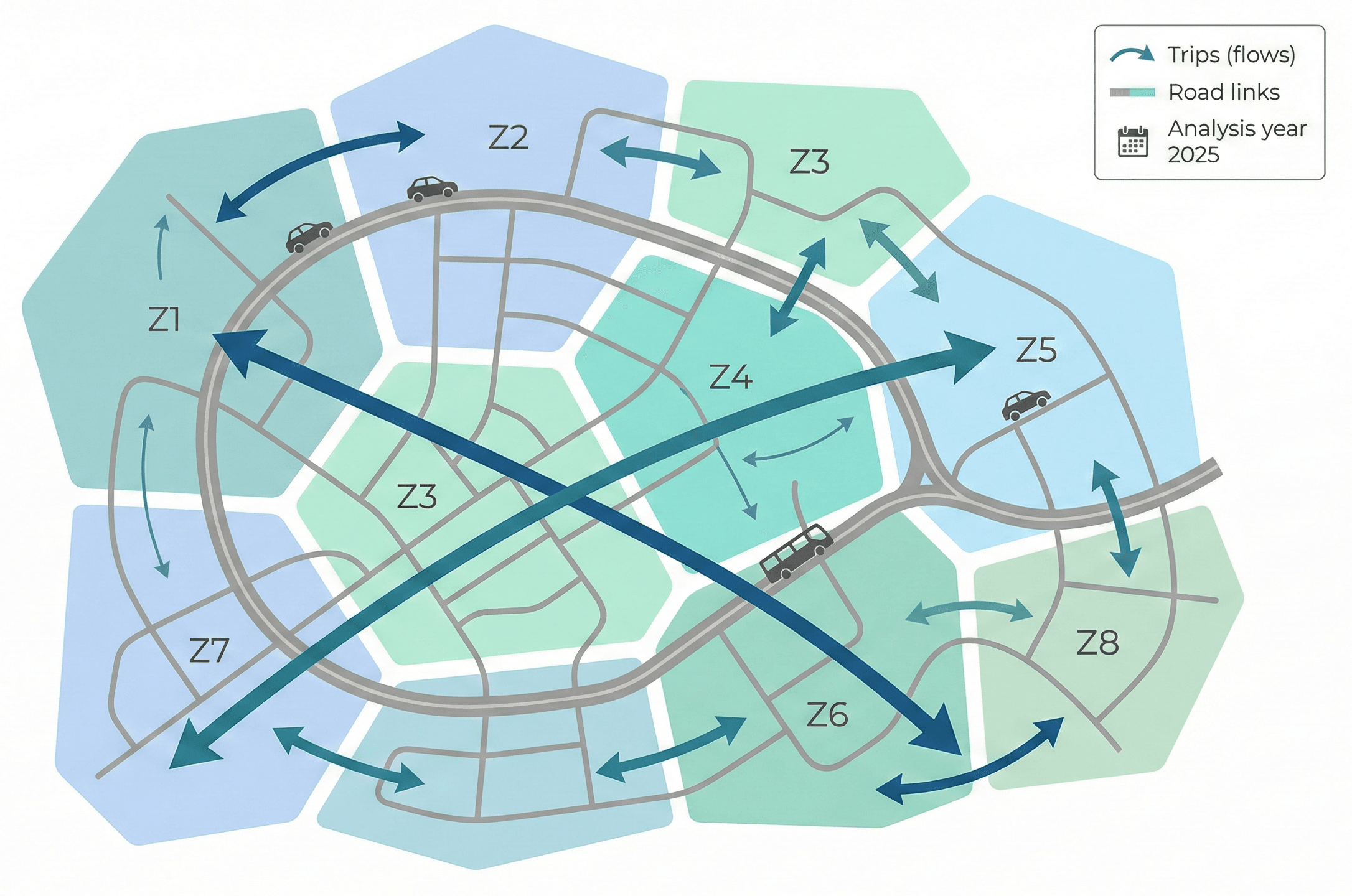

Featured diagram

Introduction

Transportation modeling is one of the core tools Transportation Engineers use to answer future-looking questions: How much traffic will this new highway interchange attract? What happens to bus ridership if frequencies double? How will a land-use change shift congestion patterns across a city?

Rather than guessing, engineers build mathematical models that represent how people and goods move today, calibrate them to observed data, and then change assumptions to test “build” and “no-build” scenarios. These models can operate at many scales—from a single corridor to an entire metropolitan region—and support both planning and preliminary design decisions.

This guide walks through what transportation modeling is, common model types, the classic four-step process, key equations and performance measures, and how calibration and validation turn a generic model into a decision-quality tool. Whether you are a student seeing these concepts for the first time or a practitioner refreshing fundamentals, the goal is to connect theory to the way models are actually used in practice.

What is transportation modeling?

Transportation modeling is the use of mathematical and computational representations of travel demand and transportation networks to predict how people and goods move under different conditions, so engineers can test scenarios and support planning, design, and operations decisions before they are built.

In practice, a transportation model combines two main ingredients: demand (who is traveling, from where to where, at what times, and by which modes) and supply (the road, transit, walking, cycling, and freight networks with their capacities and operating characteristics). The model then estimates how demand interacts with supply to produce volumes, speeds, delays, and other performance measures.

These models sit at the heart of many Transportation Engineering tasks, including corridor studies, long-range regional plans, highway and intersection design, transit network planning, and even policy analysis for pricing or emissions. For deeper background on the underlying traffic relationships, you can also see Turn2Engineering’s dedicated guide on Traffic Flow Theory.

Types of transportation models

Not all transportation models are built the same way. The “right” model depends on the questions being asked, the geographic scale, available data, and computing resources. At a high level, models can be categorized by spatial scale, behavioral detail, and purpose.

By spatial and temporal scale

- Macroscopic models: Treat flows like fluids, using aggregated relationships between volume, speed, and density. Regional travel demand models and many highway assignment models fall into this category.

- Mesoscopic models: Combine aggregate flow relationships with some individual-vehicle logic. They are often used when detail is needed on specific corridors but full microsimulation is too heavy.

- Microscopic models: Represent individual vehicles or travelers with car-following and lane-changing logic. Microsimulation is commonly used for detailed intersection, interchange, and corridor operations studies.

By purpose and questions

- Planning models: Answer long-term questions about land use, network expansion, and multimodal investment tradeoffs, often using the four-step travel demand framework described below.

- Operations models: Focus on short-term performance such as queue lengths, delay, and level of service (LOS) at specific facilities, often using traffic microsimulation combined with Highway Design and Highway Capacity Manual methods.

- Policy models: Explore pricing, parking, transit fare structures, or demand management, frequently relying on behavioral models like discrete choice or activity-based modeling.

Start with the simplest model that honestly answers the question. Adding detail (e.g., microsimulation) is only worthwhile if it changes decisions and can be supported with appropriate data, calibration effort, and review time.

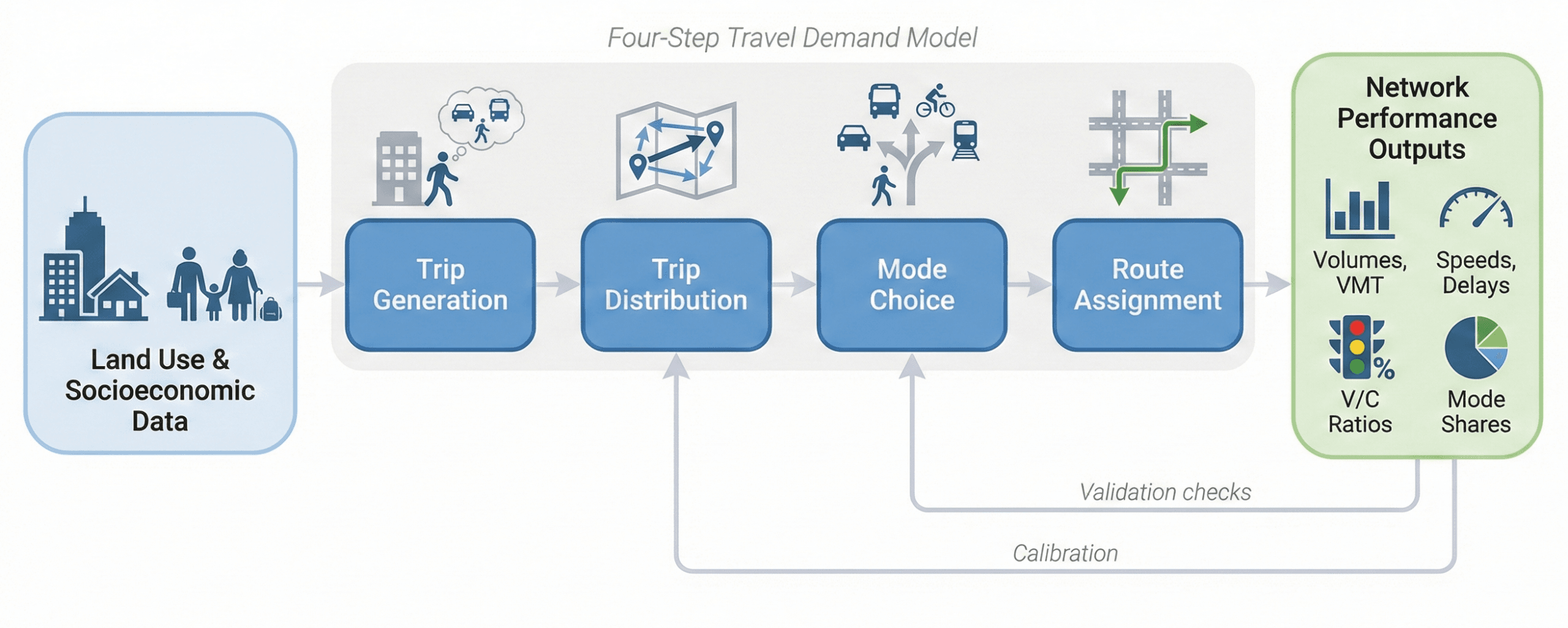

The four-step travel demand modeling process

Many planning agencies still rely on the classic four-step travel demand model. While modern methods are moving toward activity-based and agent-based models, the four steps remain a useful mental model and are still widely used in practice.

1. Trip generation

Trip generation estimates how many trips originate and end in each traffic analysis zone (TAZ) for a given time period (e.g., daily or peak hour). Equations relate land use and socio-economic variables—such as households, jobs by type, income, or car ownership—to trip productions and attractions.

2. Trip distribution

Trip distribution connects productions and attractions into an origin–destination (O–D) pattern. Gravity models are common, where trips between zones decrease with increasing travel time or cost, analogous to gravitational attraction weakening with distance. The output is an O–D matrix of trips by purpose.

3. Mode choice

Mode choice splits trips among competing modes such as driving alone, carpool, bus, rail, biking, or walking. Behavioral models (often discrete choice models) relate the attractiveness of each mode to travel time, cost, reliability, comfort, and sometimes socio-economic traits of travelers.

4. Route assignment

Route (or traffic) assignment loads trips from the O–D matrix onto specific paths through the network, respecting capacity and travel time. Deterministic or stochastic user equilibrium algorithms are often used so that no traveler can reduce their travel time by unilaterally changing routes.

At each step, compare model outputs to observed data such as counts, screenline flows, transit ridership, and mode shares. If any step is poorly calibrated, later steps may “fit” overall counts but be behaviorally unrealistic, undermining the reliability of scenario results.

Key equations and performance measures

Under the hood, transportation models use many equations. One of the most important families is discrete choice models, often used for mode choice or route choice. A common form is the multinomial logit model, which converts generalized costs or utilities into mode probabilities.

Here, \(P_i\) is the probability of choosing mode \(i\), \(C_i\) is the generalized cost of mode \(i\) (combining time, money, and sometimes reliability or comfort), and \(\theta\) is a sensitivity parameter that controls how strongly travelers respond to differences in cost. Lower-cost modes receive higher probability, but all modes retain some chance of being chosen.

- \(P_i\) Probability that a traveler chooses mode \(i\) (unitless, between 0 and 1).

- \(C_i\) Generalized cost of mode \(i\), often in minutes or monetary units after converting time via value-of-time assumptions.

- \(\theta\) Sensitivity parameter (1/cost units) estimated during calibration; higher values mean travelers react more strongly to cost differences.

Example: simple two-mode choice

Suppose travelers can choose between driving and bus. The generalized cost of driving is \(C_\text{drive} = 25\) minutes and the bus is \(C_\text{bus} = 35\) minutes, and calibration suggests \(\theta = 0.08\) per minute. The probability of driving is \[ P_\text{drive} = \frac{e^{-0.08 \cdot 25}}{e^{-0.08 \cdot 25} + e^{-0.08 \cdot 35}} \approx \frac{e^{-2}}{e^{-2} + e^{-2.8}} \approx 0.69. \] The model predicts about 69% of trips by car and 31% by bus. By adjusting times or adding costs (e.g., parking fees), you can explore how incentives shift mode shares.

Common performance measures

Once trips are assigned to the network, engineers typically report:

- Link and turning volumes (vehicles/hour or passengers/hour).

- Volume-to-capacity (v/c) ratios as indicators of congestion.

- Travel times and delays by route, corridor, or origin–destination pair.

- Vehicle-miles traveled (VMT) and vehicle-hours traveled (VHT) by scenario.

- Mode shares and ridership for transit alternatives.

For detailed capacity and LOS calculations on specific facilities, a model is often paired with methods grounded in Traffic Flow Theory and Highway Capacity Manual procedures, and sometimes with interactive tools you can find in Turn2Engineering’s engineering calculators library.

Data, calibration, and validation

A transportation model is only as good as the data and calibration behind it. Even an elegant mathematical structure will mislead decision-makers if it does not replicate current conditions within acceptable error ranges.

Key data sources

- Traffic counts and screenlines: Permanent counters, short-duration tube counts, and turning-movement counts at key intersections.

- Transit boarding data: Automatic passenger counters, farebox data, or surveys that show ridership by route and stop.

- Household and workplace data: Census, surveys, or mobile device data that describe where people live, work, and travel.

- Travel time and speed data: Probe data from GPS, floating car runs, or third-party providers to validate travel times on major routes.

Calibration

Calibration adjusts model parameters—such as trip rates, friction factors in gravity models, mode choice coefficients, or capacity and speed functions—until the model reproduces observed base-year data. Engineers target metrics like link volume errors, screenline matches, and mode share differences within agreed tolerances.

Validation and reasonableness checks

After calibration, validation tests how the model behaves under slightly different conditions or against data not used in calibration. Reasonableness checks ensure that elasticities, responses to travel time or cost, and shifts between modes or routes all “look right” to experienced modelers, even before focusing on exact numerical fit.

Never treat a calibrated model as a black box. Document data sources, calibration targets, and known limitations, and review whether the model’s responses to policy or design changes make engineering sense before relying on results for high-stakes decisions.

Using transportation models in practice

In real projects, transportation models are decision-support tools. They do not “approve” projects or substitute for judgment, but they provide a structured way to compare alternatives and communicate tradeoffs to stakeholders, agencies, and the public.

Typical applications

- Corridor and highway studies: Estimate future volumes, v/c ratios, and travel times under different lane configurations, interchange designs, or managed lane strategies.

- Transit planning: Evaluate new routes, frequency changes, bus rapid transit (BRT), or rail lines by predicting ridership, mode shifts, and network-wide effects.

- Land-use and development review: Assess how new residential, commercial, or industrial developments will affect surrounding network performance and multimodal accessibility.

- Policy analysis: Explore congestion pricing, parking policy, TDM programs, or tolling strategies before implementation.

Common pitfalls and engineering checks

- Interpreting model outputs as precise forecasts rather than approximate indicators of direction and magnitude.

- Comparing scenarios with inconsistent assumptions (e.g., different land-use baselines).

- Ignoring network bottlenecks or operational details that the model does not represent explicitly.

- Presenting detailed numbers without clearly stating uncertainty and limitations.

A frequent mistake is to focus only on one metric—like link volume on a single road—without checking network-wide impacts or multimodal performance. Always review how a scenario affects parallel routes, transit, walking, and cycling, not just the project corridor.

For more conceptual background on how modeling results feed into project prioritization and policy decisions, it is helpful to pair this page with Turn2Engineering’s guide on Transportation Planning, which zooms out to the broader planning process.

Work with real numbers

Engineering calculators & equation hub

Jump from theory to practice with interactive calculators and equation summaries covering civil, mechanical, electrical, and transportation topics.

Visualizing transportation modeling workflows

One of the clearest ways to understand transportation modeling is to see the flow of information: from land-use data and socio-economic inputs, through the four-step process, to network assignments and performance metrics.

Relevant standards and modeling references

Transportation modeling practice is anchored in guidance from national manuals and local agency documents. While tools and software evolve, these references define accepted methods, calibration practices, and reporting expectations.

- Highway Capacity Manual (HCM): Provides methodologies for estimating capacity, level of service, and performance on highways, arterials, and intersections. Often used together with model outputs to evaluate operational impacts on specific facilities.

- FHWA traffic analysis and travel demand modeling guidance: Offers best practices for regional models, microsimulation, and corridor studies, including calibration targets and documentation standards.

- Metropolitan planning organization (MPO) modeling guidelines: Many MPOs publish user guides for their regional models, detailing assumptions, base years, and appropriate use cases for scenario analysis.

- Transit agency modeling handbooks: Describe how to apply ridership forecasting, fare policy analysis, and multimodal accessibility metrics in project development and alternatives analysis.

When using a specific regional or project model, always consult the latest documentation and coordinate with the model owner to ensure you are applying the tool within its intended scope.

Frequently asked questions

Transportation modeling is the practice of representing travel demand and transportation networks with mathematical and computational models so engineers can estimate how people and goods move, test alternative futures, and support planning, design, and operational decisions before projects are built or policies are implemented.

The four-step travel demand model is a widely used framework that predicts trips by going through trip generation, trip distribution, mode choice, and route assignment. Each step refines how many trips are made, where they go, how they are made, and which paths they take across the network.

You should be comfortable with algebra, basic calculus, statistics, and probability, plus some exposure to linear algebra and optimization. In practice, you use these tools for regression, matrix operations, and discrete choice models rather than heavy derivations, so applied problem-solving skills matter more than advanced theory.

Even well-calibrated models are approximate and should be interpreted with care. They are most useful for comparing alternatives and exploring trends rather than predicting exact numbers. Accuracy depends on data quality, calibration effort, and whether the modeled scenarios fall within the range of conditions the model was built to represent.

Summary and next steps

Transportation modeling turns raw data about people, places, and networks into structured insights that guide Transportation Engineering decisions. By representing travel demand, network supply, and traveler behavior, models allow engineers to explore future scenarios, test alternatives, and communicate the tradeoffs behind major investments and policies.

The most useful models are not the most complex ones, but the ones that are carefully calibrated, transparently documented, and interpreted with sound engineering judgment. As you advance, focus on understanding how inputs, behavioral assumptions, and algorithms interact to produce outputs, and always pair model results with field knowledge and standards-based analysis.

From here, you can deepen your skills by studying traffic flow relationships, learning how planning and design decisions are made, and experimenting with small modeling exercises or calculators that make the math tangible.

Where to go next

Continue your learning path with these curated next steps.

-

Read a deeper dive on Traffic Flow Theory

Build intuition for how flow, speed, and density interact on links—critical context for interpreting model outputs and network performance.

-

See how modeling fits into Transportation Planning

Explore how technical modeling results connect to planning processes, project evaluation, and policy decisions at the corridor and regional scale.

-

Practice with related calculators on Turn2Engineering

Apply equations for speed–flow relationships, capacity, or geometric design using interactive tools that let you experiment with real numbers.

Work with real numbers

Engineering calculators & equation hub

Jump from theory to practice with interactive calculators and equation summaries covering civil, mechanical, electrical, and transportation topics.