Key Takeaways

- Definition: Geometric design of roads selects alignment and cross-section elements (using design controls and equations) to achieve safe, predictable, and comfortable vehicle operation.

- Most-used equations: Stopping sight distance, horizontal curve radius (via superelevation + friction), and vertical curve length (via required sight distance / K-values).

- Step-by-step workflow: Choose design controls → establish typical section → design horizontal alignment → design vertical profile → verify sight distance and consistency → finalize details and checks.

- Practical outcome: After this page, you’ll be able to size curves and vertical curves, estimate key lengths, and run “engineering checks” that catch unsafe geometry early.

Table of Contents

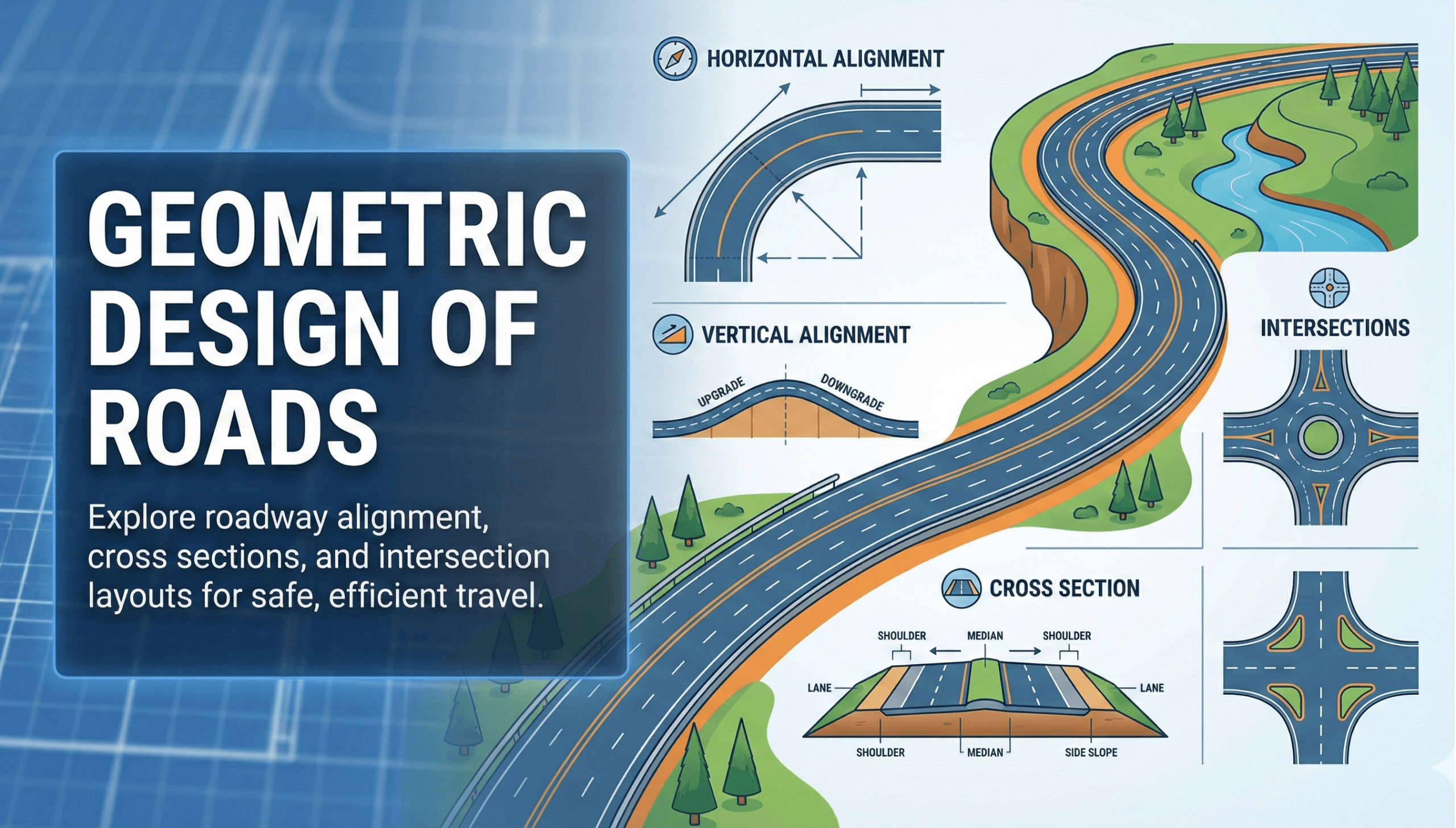

Featured diagram

Image prompt (editor only): Clean engineering illustration showing plan view curve, vertical profile with crest/sag curves, and a cross-section with lane + shoulder + cross slope, annotated with sight distance and design speed.

Introduction

Geometric design of roads is where transportation engineering becomes “driveable.” It’s the discipline that turns purpose (a local street, a rural highway, an urban arterial) into physical geometry: curves you can negotiate, grades you can climb, and sight lines that let drivers react in time. If you’ve ever felt a curve that was too sharp, a hillcrest you couldn’t see over, or a lane that felt uncomfortably narrow, you’ve experienced geometric design—good or bad.

This resource goes beyond definitions. You’ll learn a practical, step-by-step process used on real roadway projects, plus the core equations that repeatedly appear in plan/profile design: stopping sight distance, horizontal curve design with superelevation and side friction, vertical curve sizing for crest and sag conditions, and the cross-section parameters that make the alignment safe and forgiving. The goal is simple: help you design geometry that matches driver expectations and meets standard design criteria without guesswork.

Design controls you must establish first

Geometric design starts with “design controls”—the inputs that govern almost every dimension you pick later. If these are unclear, you will redesign the alignment repeatedly. In practice, most agencies require these decisions before detailed design begins.

Core design controls

- Functional classification: local street, collector, arterial, freeway; sets expectations for access, speeds, and cross-section.

- Design speed: the speed used to size curves and sight distance; ideally consistent with expected operating speed.

- Design vehicle: passenger car, single unit truck, WB-tractor trailer, emergency vehicle; affects turning paths and lane/shoulder needs.

- Terrain: level, rolling, mountainous; affects feasible grades and vertical curve lengths.

- Context and constraints: right-of-way, environment, utilities, access points, adjacent land use, drainage outlets.

- Users: cars, trucks, buses, bikes, pedestrians; context may require multimodal geometric decisions.

- VDesign speed (mph or km/h)

- DVDesign vehicle selection (governs turning / offtracking)

- eSuperelevation rate (ft/ft or m/m; often reported as %)

- fSide friction factor (dimensionless; varies with speed and conditions)

- GGrade (ft/ft or %)

- SSDStopping sight distance (ft or m)

Starting horizontal and vertical layout before locking design speed and design vehicle leads to geometry that “almost works,” then fails critical checks (especially sight distance and truck accommodation).

Sight distance: the safety backbone of geometric design

Sight distance is the length of roadway visible to a driver. In geometric design, you typically check at least stopping sight distance (SSD), and in higher-speed or more complex locations you may also check decision sight distance (DSD) or passing sight distance (PSD). When a road fails sight-distance checks, it doesn’t matter how “smooth” the geometry looks—the design is not safe.

Stopping sight distance (SSD)

SSD is the distance needed for a driver to perceive a hazard and come to a stop. A common simplified model is perception-reaction distance plus braking distance. In US customary units (mph and ft), a widely used form is:

The first term is the perception-reaction distance (with \(V\) in mph and \(t\) in seconds). The second term estimates braking distance, where \(f_b\) is the braking friction factor and \(G\) is grade expressed as a decimal (use \(+\) for upgrades, \(-\) for downgrades depending on your agency sign convention—always follow the governing manual).

- VDesign speed (mph)

- tPerception-reaction time (s); commonly 2.5 s for design checks

- f_bBraking friction factor (dimensionless; typically decreases with speed)

- GGrade (decimal; e.g., 4% = 0.04)

Decision sight distance (DSD)

DSD is longer than SSD and is used where drivers must detect an unexpected condition, understand it, decide, and then maneuver. DSD is often taken from standard tables by roadway type and environment, but conceptually it is:

where \(t_d\) is a longer “decision time” than basic perception-reaction. In practice, use your governing design reference tables for DSD by scenario (urban vs rural, complexity, and maneuver type).

If your alignment “technically meets SSD” but it feels tight (frequent hidden driveways, lane drops, or complex signage), consider whether DSD is the more appropriate controlling criterion.

Horizontal alignment: sizing curves with superelevation and friction

Horizontal alignment consists of tangents connected by curves (often circular) and sometimes transition spirals. The key design question is: for a given speed, what curve radius is safe and comfortable, and what superelevation rate should be used to help vehicles track the curve?

Minimum radius of a horizontal curve

A classic relationship ties speed to curve radius using superelevation \(e\) and side friction factor \(f\). In US customary units (mph, ft), a common form is:

This equation is the workhorse for early curve sizing. Final design should follow your agency’s adopted superelevation distribution method, maximum \(e\), and speed-dependent \(f\) values.

Superelevation rate and cross slope

Superelevation is the banking of the roadway in a curve to counteract lateral acceleration. It is commonly expressed as a rate \(e\) (ft/ft or m/m), often reported as a percent. Cross slope is the normal crown slope used for drainage on tangents.

For small angles, \(e\) can be approximated as the rise over run across the rotated roadway width. Designers typically adopt standard cross slopes (e.g., ~2%) and convert to a full superelevation in curves using a controlled “runoff” length.

Superelevation runoff length (practical sizing)

Runoff length is the distance needed to rotate the cross slope from normal crown to full superelevation. Many agencies use relative gradient methods or tabulated values. A common conceptual relationship uses the change in cross slope over length:

where \(w\) is the rotated width, \(n\) is the normal crown (as a rate), and \(RG\) is an adopted relative gradient (dimensionless). Because \(RG\) and rotation methods vary by agency, treat this as a planning equation and confirm with your governing reference.

Early in layout, choose curve radii that avoid pushing superelevation to its maximum. Geometry that “needs max e” often creates operational issues in wet/icy conditions and can be hard to fit within urban constraints.

Optional: spiral transition length (comfort-based concept)

Where spirals are used, designers often aim to control the rate of change of lateral acceleration (jerk). A conceptual form relates spiral length \(L_s\) to speed and allowable jerk \(C\):

Different manuals define constants and preferred approaches; use this relationship to understand why higher speeds and sharper curves benefit from longer transitions.

Vertical alignment: grades and vertical curves you can see over

Vertical alignment defines the roadway profile: grades connected by vertical curves. Two vertical curve types are used: crest curves (like a hilltop) and sag curves (like a valley). The primary geometric purpose is to provide adequate sight distance and smooth ride quality while balancing earthwork and drainage.

Grade

Grade is expressed as percent rise over run and drives both vehicle performance (especially trucks) and braking demands. It is computed as:

Vertical curve parameter: algebraic grade difference

The main “input” to a vertical curve is the algebraic difference in grades:

where \(g_1\) and \(g_2\) are the incoming and outgoing grades (in %). The required curve length \(L\) depends on whether a crest or sag curve is controlling and the required sight distance.

K-value approach (common in practice)

Many design procedures express vertical curve length using the K-value:

K-values are usually selected from standard tables for required sight distance at a given speed and curve type (crest vs sag). This makes design fast: once \(A\) is known, pick \(K\) and compute \(L\).

Crest vertical curve sight distance (conceptual form)

Crest curves are commonly controlled by line-of-sight over the roadway. One common simplified conceptual representation is that \(L\) must scale with \(SSD^2/A\) when the curve is long relative to the sight distance:

Because constants depend on assumed eye height and object height and on whether \(L \ge SSD\) or \(L < SSD\), agencies typically provide direct equations or K-value tables. The key point: higher speeds (larger SSD) and tighter grade breaks (larger \(A\)) demand longer crest curves.

Sag vertical curve (headlight control at night)

Sag curves are often controlled at night by headlight beam geometry. As with crest curves, manuals provide equations or K-values based on headlight height and beam angle, with length increasing strongly with speed/sight-distance needs.

Designers sometimes size vertical curves for comfort only and forget that the controlling criterion may be sight distance—especially at crest curves where the line-of-sight can be unexpectedly restrictive.

Cross-section design: lane/shoulder sizing, slopes, and the “forgiving road” concept

Cross-section design is where roadway geometry meets real-world safety outcomes. Even if plan and profile meet curve equations, poor cross-section choices (insufficient shoulders, steep slopes, inconsistent cross slopes) can create higher crash severity and maintenance issues.

Cross slope for drainage and comfort

On tangents, cross slope \(n\) is selected to drain water without feeling unstable. In curves, cross slope transitions to full superelevation. A simple geometric relationship for slope is:

where \(\Delta h\) is the vertical drop across width \(w\). The “right” value is typically set by standard practice and climate (rain/ice) rather than calculation alone.

Lane widening on sharp curves (concept)

On tight curves, large vehicles offtrack (rear wheels cut inside the front path). Agencies sometimes require additional widening. A simplified conceptual dependency is:

where \(W_e\) is extra widening and \(R\) is curve radius. Detailed widening depends on design vehicle and tracking calculations (usually done with vehicle-swept path tools rather than hand equations).

Roadside recovery space (clear zones and slopes)

A “forgiving road” gives an errant driver space to recover before a fixed object or steep slope. While clear-zone width is normally selected from design guidance tables (speed/traffic/side slope), geometric design should always consider:

- Recoverable vs non-recoverable side slopes

- Placement of fixed objects (sign supports, poles, trees)

- Need for barriers where hazards cannot be removed or graded

If right-of-way constraints force minimal shoulders or steep side slopes, treat it as a design risk early and coordinate with safety, drainage, and utility teams before the alignment is “locked.”

Step-by-step: how to design roadway geometry (a practical workflow)

This workflow is written the way roadway designers actually iterate: you start with controlling decisions, lay out geometry, then verify and refine. The checkpoints are as important as the calculations.

- Define project purpose and functional classification. Identify whether the road prioritizes access (local/collector), movement (arterial), or mobility (freeway). This frames design speed, access spacing, and cross-section expectations.

- Select design speed and controlling design vehicle. Use context, adjacent network, and agency policy. Confirm whether heavy vehicles or emergency turning needs govern.

- Establish the typical section (cross-section baseline). Decide lane widths, shoulder widths, median type, and basic cross slopes. Confirm drainage strategy and available right-of-way.

- Lay out preliminary horizontal alignment. Place tangents and curves to fit constraints. Use the curve-radius equation \(R = V^2/[15(e+f)]\) to avoid radii that force extreme superelevation or low comfort.

- Design superelevation transitions. Choose superelevation rate \(e\) consistent with agency practice and climate. Size runoff/tangent runout as required by the governing reference method.

- Develop preliminary vertical profile. Select grades that fit terrain and drainage needs. Add crest/sag vertical curves at grade breaks and estimate lengths using K-values or sight-distance equations.

- Check sight distance everywhere it can break. Check SSD (and DSD where appropriate) on crests, inside horizontal curves with roadside obstructions, and near intersections/driveways as required.

- Run design consistency checks. Compare expected operating speed to design speed across successive curves and grades. Look for “surprise geometry” such as a sharp curve immediately after a long tangent.

- Refine with constraints and constructability. Balance earthwork, drainage outlets, utility conflicts, and right-of-way. Iterate alignment to reduce extreme grades or superelevation needs.

- Finalize and document assumptions. Record design controls, governing criteria, and any approved exceptions. These become critical later for reviews, safety audits, and future rehabilitation projects.

Keep a running “control sheet” as you design: design speed, e max, selected friction factors, required SSD/DSD, chosen K-values, typical section dimensions, and controlling constraints. It prevents rework and makes reviews faster.

Worked example: curve radius + SSD + vertical curve length

This example shows how designers combine the most common geometric checks. The numbers are illustrative; always use your agency’s adopted friction factors, SSD values, and K-tables for final design.

Example

Given: Two-lane rural roadway, proposed design speed \(V = 55\) mph. Assume a superelevation rate \(e = 0.06\) (6%). Use a planning side friction factor \(f = 0.12\). Grades transition from \(g_1 = +2.0\%\) to \(g_2 = -1.0\%\) at a crest. Assume planning SSD uses \(t = 2.5\) s, braking friction \(f_b = 0.35\), and level grade for the SSD check (conservative for upgrades, less conservative for downgrades depending on sign convention).

1) Minimum horizontal curve radius

A planning minimum radius is approximately 1,120 ft. In design, you would choose a larger radius if feasible to improve comfort and provide margin for friction variations and wet conditions.

2) Planning stopping sight distance

This yields a planning SSD of roughly 490 ft. Compare this to your agency’s SSD table for 55 mph and adopt the governing value.

3) Vertical curve inputs and length

Compute algebraic grade difference:

Next, select an appropriate crest K-value from the governing design reference based on the required SSD for 55 mph. Once K is selected:

Interpretation: The faster your design speed (larger SSD) and the sharper the grade break (larger \(A\)), the longer the crest curve must be. If the resulting length is difficult to fit, you can reduce \(A\) by adjusting grades or shifting the profile to “soften” the grade change.

After you pick a curve radius and vertical curve length, verify that any roadside obstructions (barriers, walls, vegetation, cut slopes) do not block required sight distance on the inside of the curve or near the crest.

Common pitfalls and geometry checks that prevent redesign

Geometric design problems rarely come from one “bad equation.” They come from inconsistency across elements: a curve that meets radius criteria but fails sight distance, or a profile that drains but creates uncomfortable speed changes. The checks below are the ones practitioners rely on repeatedly.

High-impact pitfalls

- Mixing unit systems: mph/ft formulas versus SI formulas—lock your unit system early and stick to it.

- Designing to the minimum everywhere: minimum radii and minimum K-values often yield geometry that technically passes but performs poorly in the field.

- Forgetting inside-of-curve sight obstructions: barriers, walls, and cut slopes frequently reduce available sight distance.

- Ignoring heavy vehicle needs on grades: long upgrades can create speed differentials that affect safety and operations.

- Overlooking drainage in cross-slope transitions: poor runoff control can create ponding, especially near superelevation transitions.

Treating plan, profile, and cross-section as separate tasks. In reality, the controlling issue might come from their interaction (e.g., a crest curve that sits inside a horizontal curve with limited lateral clearance).

Useful “at-a-glance” table for early design

These are planning-level reminders (not a substitute for your governing manual). Use them to organize checks and make sure nothing gets forgotten during early layout.

| Design item | What you size/check | Most common controlling input | Where issues show up |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stopping sight distance (SSD) | Required visible length along roadway | Speed + reaction/braking assumptions | Crest curves, inside of horizontal curves, access points |

| Horizontal curve | Radius, superelevation, transitions | Speed, e max, friction factors | Run-off-road crashes, discomfort, winter operations |

| Vertical curve | Length (often via K and A) | SSD/DSD and grade break magnitude | Hidden hazards at crests, headlight limitations at sags |

| Cross-section | Lane/shoulder widths, slopes | Vehicle mix, ROW, drainage | Run-off-road severity, maintenance, drainage ponding |

Work with real numbers

Engineering calculators & equation hub

Jump from theory to practice with interactive calculators and equation summaries covering civil, mechanical, electrical, and transportation topics.

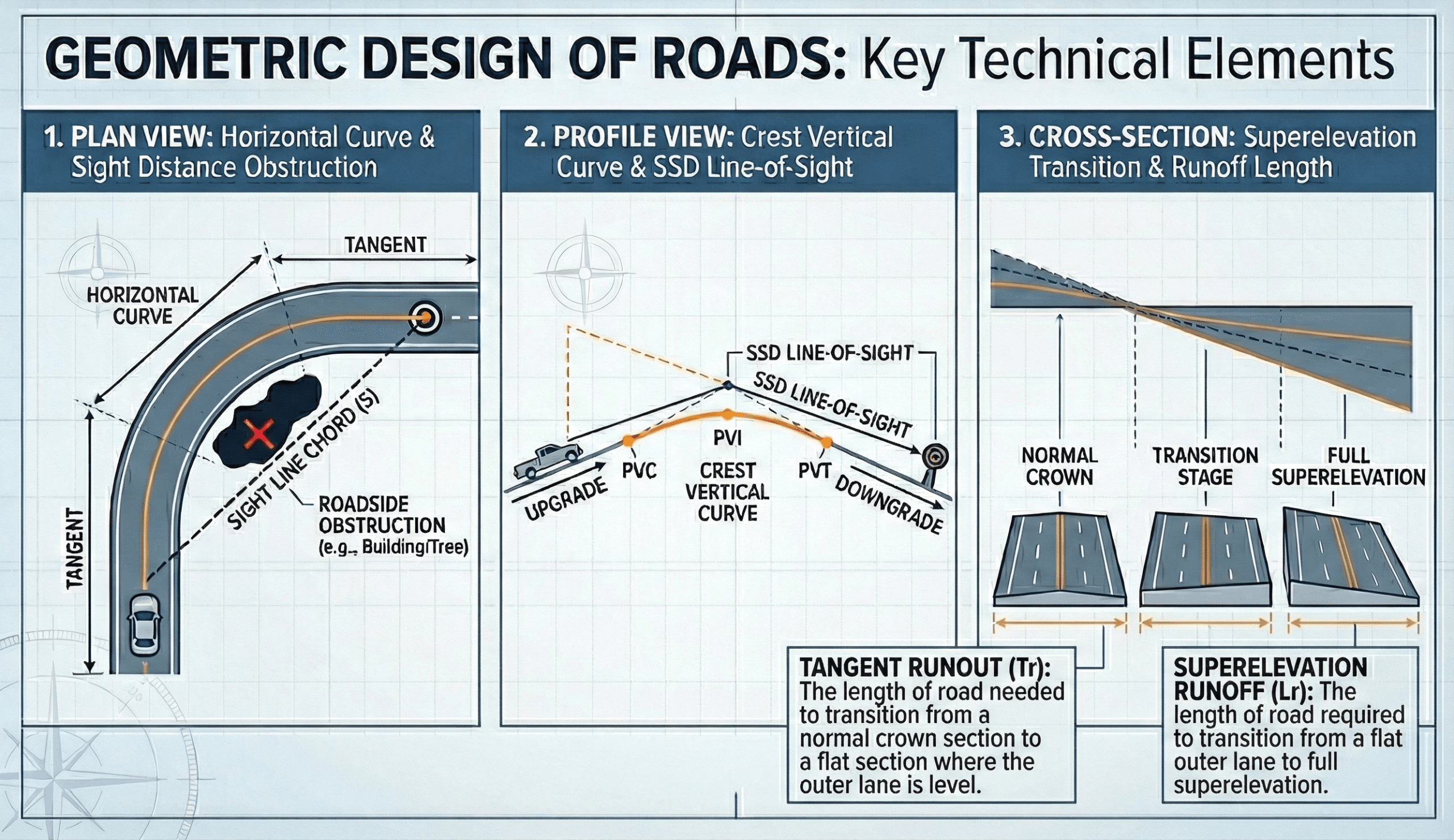

Visualizing geometric road design (what to sketch on day one)

A fast way to understand (and communicate) geometric design is to sketch the same roadway three ways: plan view (horizontal alignment), profile view (vertical alignment), and cross-section (typical section). If you can sketch these with the key variables labeled, you can usually spot design problems before running a full model.

Recommended sketch: Draw a horizontal curve with an inside obstruction (such as a cut slope or barrier) and label the required sight line. Below it, draw a crest vertical curve at the same location and label stopping sight distance (SSD). Finally, draw the cross-section and show how cross slope transitions into full superelevation through runoff.

If the geometry works in only one view but feels forced in the others, revise the alignment early. Most geometric design failures occur where horizontal alignment, vertical profile, and roadside clearance interact.

Relevant standards and design references

Geometric design is standards-driven. Use the references below to select official values for friction factors, superelevation limits, SSD/DSD tables, K-values for vertical curves, and cross-section criteria. This page explains the “why” and the workflow; standards provide the adopted “what.”

- AASHTO “Green Book” (Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets): Primary reference for alignment, cross-section, and sight-distance criteria; commonly the baseline for state DOT manuals.

- FHWA guidance and publications: Practical implementation guidance and research-based updates that often inform agency policy (especially for safety and context-sensitive solutions).

- State DOT roadway design manuals: Where project-specific requirements live (e max values, friction tables, local SSD/K-values, typical section standards, and documented exceptions).

- Highway Safety Manual (HSM) concepts (as applicable): Useful for understanding how geometric features influence crash risk and where safety-driven design changes have the most impact.

Frequently asked questions

Geometric design sets the roadway shape and dimensions (alignment, cross-section, and sight distance), while pavement design determines the layer structure and materials needed to carry traffic loads over time. Geometry influences safety and operations, while pavement design focuses on structural performance and durability.

Not usually—minimum values are safety thresholds, not performance targets. Where feasible, using larger radii and smoother alignment improves comfort, reduces reliance on high superelevation, and provides more margin for weather, speed variation, and construction tolerance.

Algebra, basic trigonometry, and comfort with units are the essentials, plus a conceptual understanding of kinematics for braking and lateral acceleration. Most day-to-day design relies on standard tables and a few core equations, with software handling detailed geometry and drafting.

You’ll use it in new roadway corridors, widening and rehabilitation projects, intersection reconstructions, safety improvements (curve flattening, crest reduction), and any project where alignment changes trigger updated sight-distance and standards compliance checks.

Start with design speed consistency and sight distance—those two issues create the strongest mismatch between driver expectation and roadway geometry. Next, check superelevation transitions and cross slopes for drainage and comfort problems that can make an alignment feel unstable.

Summary and next steps

Geometric design of roads is the disciplined process of shaping a roadway so it operates safely and predictably. It begins with design controls (functional class, design speed, design vehicle, terrain), then builds plan and profile geometry using a small set of repeated relationships: stopping sight distance to protect reaction and braking, horizontal curve sizing with superelevation and friction to control lateral demand, and vertical curve sizing (often via K-values) to ensure drivers can see and respond over crests and through sags.

The most important takeaway is that geometric elements are interdependent. A design that is “okay” in plan view can fail in profile, and a design that meets equation checks can still perform poorly if cross-section and roadside recovery space are not treated seriously. Use the step-by-step workflow, run the sight-distance checks early, and apply consistency checks so the road drives the way users expect.

Where to go next

Continue your learning path with these curated next steps.

-

Traffic Engineering

Connect roadway geometry to operations, safety performance, and real-world driver behavior.

-

Traffic Flow Theory

Learn the foundational relationships behind speed, density, flow, and why geometry influences congestion.

-

Signal Timing and Phasing

See how intersection geometry and control strategy work together to shape capacity and safety.

Work with real numbers

Engineering calculators & equation hub

Jump from theory to practice with interactive calculators and equation summaries covering civil, mechanical, electrical, and transportation topics.