Electrical Engineering · Coulomb’s Law

Coulomb’s Law – electric force between point charges explained

Coulomb’s Law relates the magnitude of the electrostatic force between two point charges to the product of their charges and the inverse square of the distance between them, forming the starting point for most electrostatics problems in engineering and physics.

Quick answer: what Coulomb’s Law tells you

Core formula for the electric force

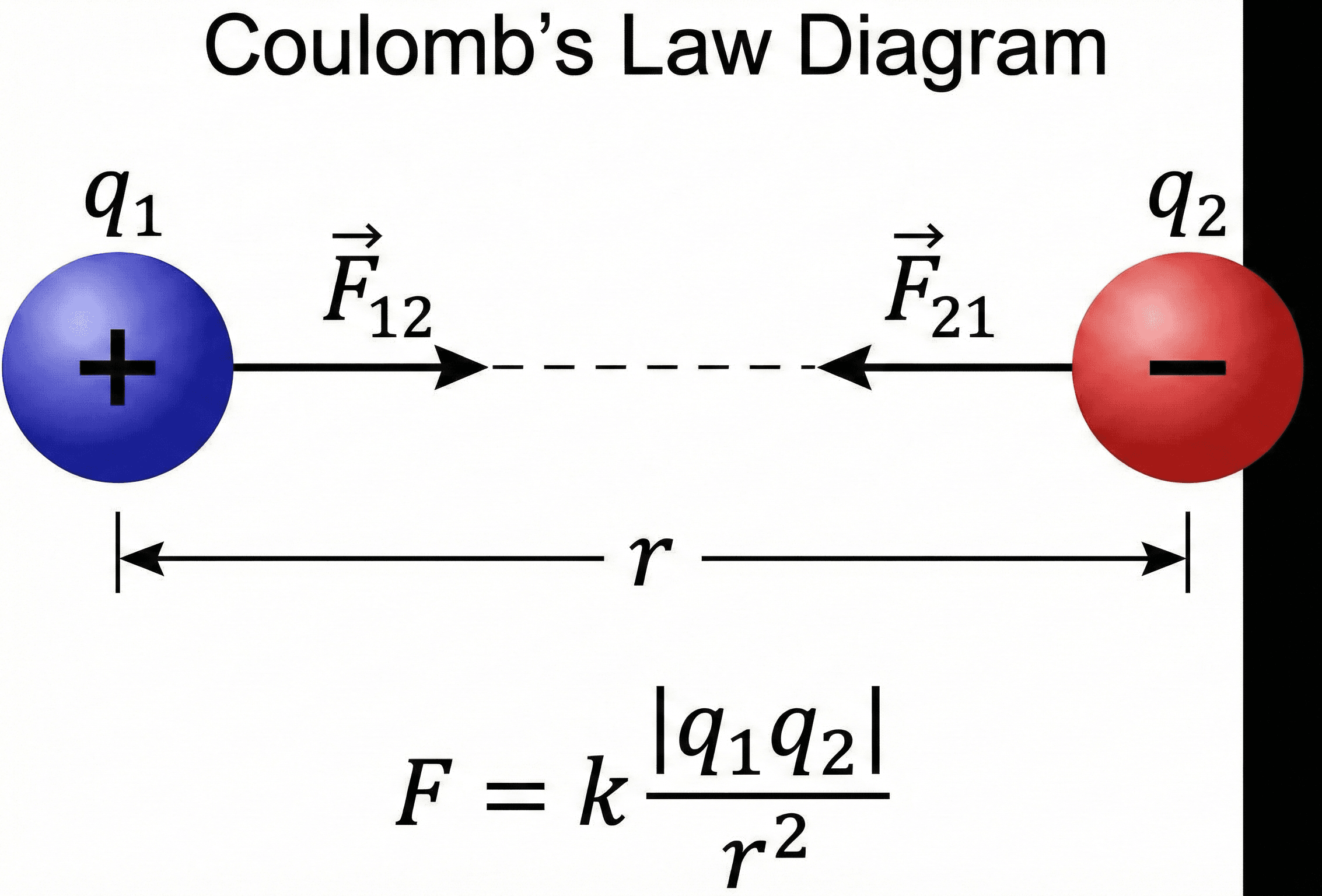

Coulomb’s Law states that the magnitude of the electrostatic force between two point charges is proportional to the product of their charges and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. Like charges repel, unlike charges attract, and the force acts along the line joining the charges.

In practice, Coulomb’s Law is the electrostatics equivalent of a “first principles” equation. It tells you how strong the force is between two charges \(q_1\) and \(q_2\) separated by a distance \(r\), assuming the charges are small compared to that distance and sit in a simple medium (usually air or vacuum). As the separation doubles, the force drops by a factor of four; if one charge is doubled, the force doubles. This inverse-square behavior mirrors other central-force laws like Newton’s law of gravitation.

Engineers often use Coulomb’s Law conceptually when reasoning about capacitors, insulation clearances, ESD (electrostatic discharge), or the local electric field near conductors. For more complex geometries, you typically replace the simple two-charge picture with superposition over many charges or continuous charge densities—but the building block remains the same law you see here. As we’ll see in the worked examples, a solid grasp of the basic two-charge case makes it much easier to understand more advanced electrostatic designs.

Symbols, units & notation in Coulomb’s Law

In its scalar magnitude form, Coulomb’s Law for two point charges is \( F = k_e |q_1 q_2| / r^2 \). In vector form, you often see \(\vec{F}_{12} = k_e \, \dfrac{q_1 q_2}{r^2}\,\hat{r}_{12}\), where the direction is captured by the unit vector \( \hat{r}_{12} \) from \(q_1\) to \(q_2\). The table below summarizes the most common symbols and engineering units.

Common notation for Coulomb’s Law

| Symbol | Quantity | SI Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( F \) | Electric force (magnitude) | Newton (N) | Magnitude of the electrostatic force between two point charges. Direction is along the line joining the charges. |

| \( \vec{F}_{12} \) | Force on \(q_2\) due to \(q_1\) | Newton (N) | Vector force exerted on charge \(q_2\) by \(q_1\). Equal and opposite to \(\vec{F}_{21}\) by Newton’s Third Law. |

| \( q_1, q_2 \) | Point charges | Coulomb (C) | Idealized point charges. Sign (positive or negative) determines whether the force is attractive or repulsive. |

| \( r \) | Separation distance | Meter (m) | Center-to-center distance between the charges. Coulomb’s Law assumes \(r\) is large compared to the physical size of each charge distribution. |

| \( k_e \) | Coulomb constant | N·m²/C² | Proportionality constant in vacuum: \( k_e = \dfrac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon_0} \approx 8.988 \times 10^9~\text{N·m}^2/\text{C}^2 \). |

| \( \varepsilon_0 \) | Permittivity of free space | F/m | Vacuum permittivity: \( \varepsilon_0 \approx 8.854 \times 10^{-12}~\text{F/m} \). Appears in the alternative form \( F = \dfrac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon_0}\,\dfrac{|q_1 q_2|}{r^2} \). |

| \( \varepsilon_r \) | Relative permittivity | – (dimensionless) | Material-dependent factor used for dielectrics. In a medium, \( k_e \) is effectively reduced by \( \varepsilon_r \) so the force is \( F = \dfrac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon_0 \varepsilon_r}\,\dfrac{|q_1 q_2|}{r^2} \). |

Unit systems & quick notes

- SI is standard: charge in coulombs, distance in meters, force in newtons. This is the default for most engineering work and textbooks.

- Magnitude vs. sign: the absolute value \(|q_1 q_2|\) in the scalar formula gives the magnitude. Direction (attractive vs. repulsive) is handled separately by the signs of the charges and the vector form.

- Medium matters: in air, using the vacuum value of \(k_e\) is often a good approximation. In high-permittivity materials, you must include the relative permittivity \(\varepsilon_r\) to get realistic forces.

Once the symbols and units are clear, Coulomb’s Law becomes a straightforward plug-and-chug equation—especially when combined with superposition and electric field definitions in later electrostatics topics.

How Coulomb’s Law behaves and when it applies

Coulomb’s Law is an inverse-square law: the electric force falls off as \(1/r^2\). That means most of the interaction happens when charges are relatively close, and small changes in spacing can cause large changes in force. The law is strictly valid for point charges, but it also works well for small charged objects when the separation is much larger than their size.

In vector form, the law captures both magnitude and direction:

Here, \( \hat{r}_{12} \) is a unit vector pointing from \(q_1\) to \(q_2\). If \(q_1 q_2 > 0\), the force on each charge points away from the other (repulsion). If \(q_1 q_2 < 0\), the force on each charge points toward the other (attraction). Newton’s Third Law guarantees that the forces are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction.

Relating Coulomb’s Law to electric field and permittivity

Coulomb’s Law underpins the definition of electric field. The field produced by a point charge \(q_1\) at distance \(r\) is defined as force per unit positive test charge:

This is why you often see the combination \(\dfrac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon_0}\) in electromagnetic formulas. In a material with relative permittivity \(\varepsilon_r\), the effective constant becomes

Higher \(\varepsilon_r\) “softens” electric interactions by reducing both field and force. This is exactly how dielectric materials in capacitors increase capacitance: they allow the same charge to sit at a lower electric field level.

Superposition and moving beyond two charges

Real electrostatic problems rarely involve just two isolated charges. Instead, you have many charges distributed in space. Coulomb’s Law still applies, but you invoke the principle of superposition: the net force on any charge is the vector sum of Coulomb forces from all other charges.

In discrete cases (a few charges), you can compute this by hand. For continuous charge distributions (lines, surfaces, volumes), you replace the sum with integrals. In either case, the building block is still Coulomb’s Law—just applied repeatedly and summed.

Coulomb’s Law is most accurate for static or slowly varying charges, where magnetic effects are negligible and the configuration does not change significantly during the time of interest. At very high frequencies or in rapidly changing fields, you need the full machinery of Maxwell’s equations, but the intuition built from Coulomb’s Law remains valuable when you sanity-check field strengths and forces in simplified scenarios.

Worked examples using Coulomb’s Law

The examples below mirror the kinds of questions students and engineers commonly ask: “What is the force between two charges?”, “How far apart do charges need to be to keep forces below a limit?”, and “How does a dielectric medium change the force?” The same step-by-step workflow can be adapted to more complex electrostatics problems.

Example 1 – Force between two small charges in air

Two point charges, \(q_1 = +2.0~\mu\text{C}\) and \(q_2 = -5.0~\mu\text{C}\), are separated by \(r = 0.30~\text{m}\) in air. Treat air as vacuum. What is the magnitude of the force between them, and is it attractive or repulsive?

- Convert microcoulombs to coulombs.

- Apply Coulomb’s Law to compute the force magnitude.

- Use the signs of the charges to determine whether the force is attractive or repulsive.

Result: The magnitude of the force is roughly \(1.0~\text{N}\). Because the charges have opposite signs, the force is attractive: each charge pulls the other toward itself along the line connecting them.

Example 2 – Required spacing to limit electrostatic force

An engineer wants to keep the electrostatic force between two identical positively charged beads below \(0.05~\text{N}\). Each bead carries \(q = +3.0~\mu\text{C}\). Assuming the beads are in air (vacuum approximation), what minimum separation distance \(r_{\text{min}}\) is needed so that \(F \le 0.05~\text{N}\)?

- Write Coulomb’s Law and solve algebraically for \(r\).

- Plug in the target force and given charges.

- Interpret the required spacing in more familiar units (e.g., centimeters).

Result: The beads must be separated by at least about \(1.3~\text{m}\) to keep the electrostatic repulsion under \(0.05~\text{N}\). This kind of back-of-the-envelope check is useful when assessing clearances in high-voltage experimental setups.

Example 3 – Effect of a dielectric medium on force

Suppose the charges from Example 1 (\(q_1 = +2.0~\mu\text{C}\), \(q_2 = -5.0~\mu\text{C}\), \(r = 0.30~\text{m}\)) are placed in a liquid with relative permittivity \(\varepsilon_r = 20\). How does the force change compared with air?

In a medium, the effective Coulomb constant is divided by \(\varepsilon_r\). The new force magnitude is \( F_{\text{medium}} = \dfrac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon_0\varepsilon_r}\,\dfrac{|q_1 q_2|}{r^2} = \dfrac{F_{\text{vacuum}}}{\varepsilon_r} \).

Result: The attractive force drops from about \(1.0~\text{N}\) in air to about \(0.05~\text{N}\) in a medium with \(\varepsilon_r = 20\). This illustrates how high-permittivity dielectrics can dramatically reduce electrostatic forces—which is exactly why they are valuable in capacitor design and electrical insulation.

Design tips, limits & checks when using Coulomb’s Law

In engineering contexts, Coulomb’s Law is more than an academic formula: it guides how you think about clearances, insulation strength, charge buildup, and forces in precision instrumentation. At the same time, there are clear limits to where the simple point-charge model applies. The notes below highlight patterns and pitfalls that frequently show up in design work.

Coulomb’s Law assumes that each charge can be treated as a point. This is a good approximation when the separation distance \(r\) is much larger than the physical size of each charged object.

- If \(r\) is only a few times larger than object size, field non-uniformity becomes important and the simple formula loses accuracy.

- Extended conductors (plates, wires, spheres) often require integrating charge distributions or using known field formulas instead of a single point-charge model.

- For tightly spaced electrodes, numerical field solvers or analytic field expressions are more reliable than a raw Coulomb estimate.

The value \(k_e \approx 8.988 \times 10^9~\text{N·m}^2/\text{C}^2\) is strictly for vacuum. In real devices, the space between charges is filled with air, oil, plastic, ceramic, or other dielectrics.

- For air at moderate humidity and spacing, treating it as vacuum is often adequate for force estimates.

- In high-permittivity materials, use \( \varepsilon = \varepsilon_0 \varepsilon_r \) and reduce the force by \( \varepsilon_r \).

- In non-uniform media (e.g., air gaps plus solid insulators), local field strength may differ significantly from a simple Coulomb or parallel-plate estimate.

A few quick checks can prevent large errors when applying Coulomb’s Law in calculations or simulations.

- Verify units: charge in coulombs, distance in meters, force in newtons. Microcoulomb vs. coulomb mistakes routinely lead to forces off by factors of \(10^6\).

- Remember that the scalar equation gives magnitude only—always add direction (sign or vector direction) separately.

- Don’t forget that multiple charges superpose: the net force is not just from the “nearest” charge but the vector sum of all relevant contributors.

When computations suggest very large electrostatic forces or extremely high local fields, that’s often a signal to step back and refine the model: include realistic geometry, dielectric interfaces, and possibly time-varying behavior. Coulomb’s Law remains the conceptual foundation, but high-stakes designs (like HV insulation or precision beams in accelerators) rely on more detailed analysis once the basic numbers look critical.

Coulomb’s Law – FAQ

What is Coulomb’s Law in simple terms?

In simple language, Coulomb’s Law says that electric charges push or pull on each other, and the strength of that push or pull depends on how big the charges are and how far apart they are. Bigger charges mean stronger forces, and moving them farther apart weakens the force very quickly (with the square of the distance). Like charges repel, unlike charges attract.

How do you use Coulomb’s Law to calculate force between two charges?

To use Coulomb’s Law, convert all quantities to SI units, then plug into \( F = k_e |q_1 q_2| / r^2 \). Use \(q_1\) and \(q_2\) in coulombs and \(r\) in meters. The result is the magnitude of the force in newtons. You then decide on direction: if the charges have the same sign, the force is repulsive (arrows pointing away from each other); if they have opposite signs, the force is attractive (arrows pointing toward each other).

Does Coulomb’s Law work in all materials?

The basic form with \(k_e = 1/(4\pi\varepsilon_0)\) is exact in vacuum and usually a good approximation in air for moderate field strengths. In other materials, you must include the relative permittivity \(\varepsilon_r\). The force is reduced by \(\varepsilon_r\), so more polarizable materials (with larger \(\varepsilon_r\)) weaken the interaction between charges. In highly non-uniform or nonlinear materials, you rely on more detailed field models, but Coulomb’s Law still underlies the basic physics.

How is Coulomb’s Law different from the gravitational force law?

Mathematically, Coulomb’s Law and Newton’s gravitational law are both inverse-square laws, but they describe different interactions. Gravity is always attractive and depends on mass. Electric forces can be attractive or repulsive and depend on charge. In many microscopic situations, electric forces are vastly stronger than gravitational forces, which is why charge distributions and electric fields dominate the behavior of electrons, ions, and many materials.

References & further reading

- Standard undergraduate electromagnetics textbooks covering electrostatics, Coulomb’s Law, electric fields, and Gauss’s Law, with example problems and derivations.

- Introductory physics texts focusing on electricity and magnetism, which provide accessible explanations of Coulomb’s Law, electric field, and potential energy of point charges.

- Application notes and technical guides from high-voltage equipment manufacturers discussing clearance distances, dielectric materials, and how electrostatic forces influence insulation design.