Relativity & Nuclear Engineering · Mass–Energy Equivalence Equation

Mass–Energy Equivalence Equation – how \( E = m c^2 \) turns mass into energy

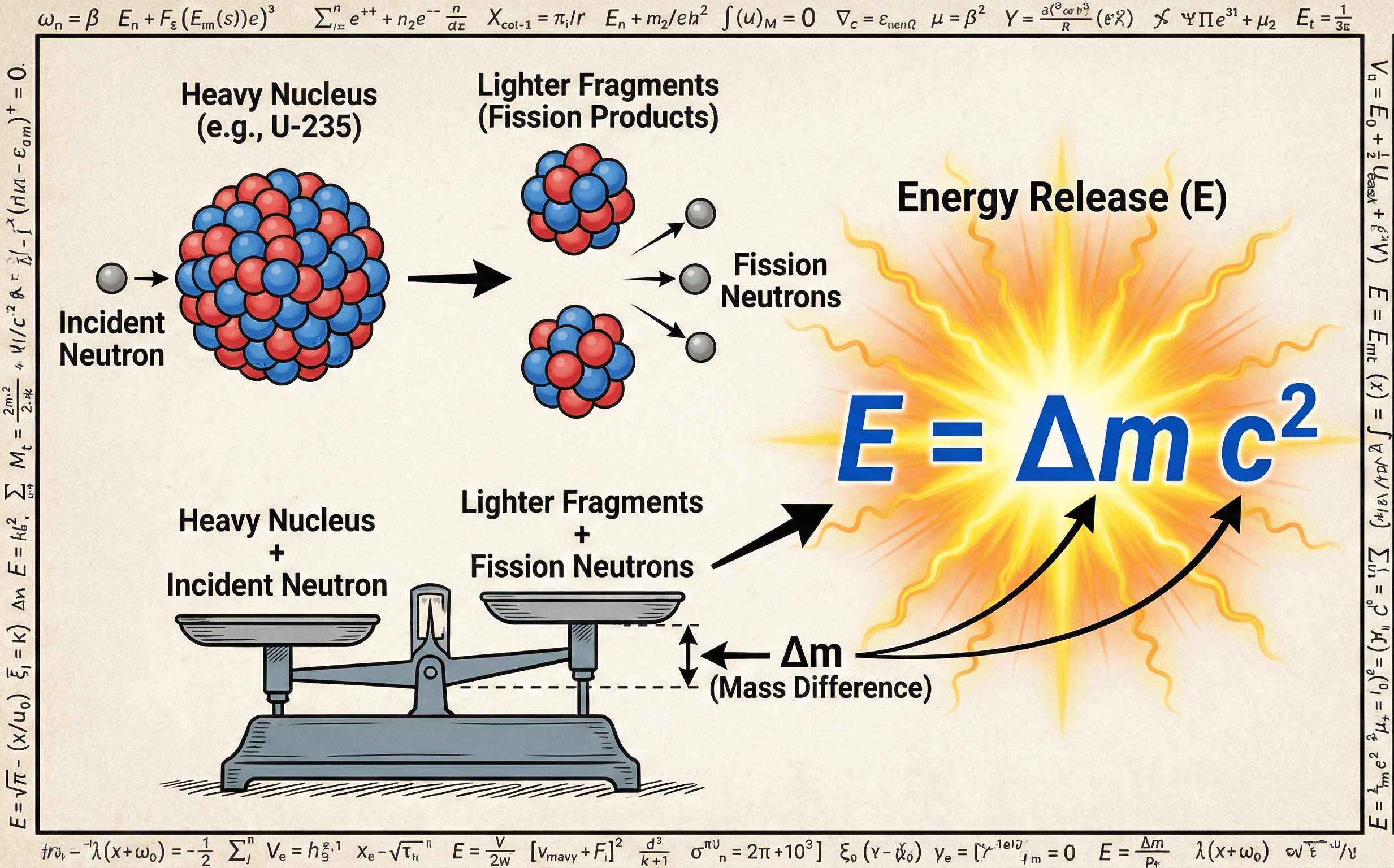

The mass–energy equivalence equation \( E = m c^2 \) shows that any mass corresponds to an enormous amount of energy, forming the basis for nuclear power, particle physics, and high-energy astrophysics calculations.

Quick answer: what the mass–energy equivalence equation says

Core formula (rest energy)

The mass–energy equivalence equation states that a body with mass \(m\) possesses an intrinsic “rest energy” \(E\) equal to its mass times the square of the speed of light, meaning that mass and energy are two forms of the same physical quantity.

In everyday engineering you rarely convert mass entirely into energy, but in nuclear reactors, fusion devices, particle accelerators, and high-energy astrophysics, even a tiny difference in mass \(\Delta m\) can release huge amounts of energy. The mass–energy equivalence equation provides the bridge: once you know how much mass is “missing” between reactants and products, you can compute the energy released as heat, radiation, or kinetic energy. You can see this workflow in the worked examples below.

The version above, \( E = m c^2 \), refers specifically to the rest energy of a body. In more complete relativistic mechanics, the total energy includes kinetic and potential contributions as well, but for many engineering calculations it is the rest energy and mass defect that matter most.

Symbols, units & notation in the mass–energy equivalence equation

In its simplest and most widely used form, the mass–energy equivalence equation is written as \( E = m c^2 \). In nuclear engineering you will also see the mass change written explicitly as \( E = \Delta m c^2 \), emphasizing that it is the difference between initial and final mass that becomes energy.

Common notation for \( E = m c^2 \)

| Symbol | Quantity | Typical unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( E \) | Energy | Joule (J) or eV / MeV | Total energy associated with the mass (often released energy in a reaction). In SI, \(1~\text{J} = 1~\text{kg·m}^2/\text{s}^2\). In nuclear and particle physics, electron-volts (eV) and mega-electron-volts (MeV) are more convenient. |

| \( m \) | Mass | kg, u (atomic mass unit) | Rest mass of the body or system. In nuclear problems \(m\) is often given in atomic mass units (u), where \(1~\text{u} \approx 1.6605 \times 10^{-27}~\text{kg}\). |

| \( \Delta m \) | Mass defect | kg, u | Difference in mass between reactants and products in a reaction or binding process. This is the mass converted into other forms of energy, with \( E = \Delta m c^2 \). |

| \( c \) | Speed of light in vacuum | m/s | Constant speed of light: \( c \approx 2.9979 \times 10^8~\text{m/s} \). Squared, it acts as the large conversion factor between mass and energy. |

| \( E_0 \) | Rest energy | J or MeV | Energy a body has by virtue of its mass alone, with no kinetic or potential contributions: \( E_0 = m c^2 \). |

Unit systems & practical conversion factors

- SI engineering work: use \(m\) in kg and \(c\) in m/s, giving \(E\) in joules. This is natural when comparing to mechanical work, heat transfer, or electrical power.

- Nuclear & particle physics: often use mass in atomic mass units and energy in MeV. A very common shortcut is \(1~\text{u} \approx 931.5~\text{MeV}/c^2\), so a mass defect of \(0.01~\text{u}\) corresponds to roughly \(9.3~\text{MeV}\).

- Joule–eV conversions: \(1~\text{eV} \approx 1.602 \times 10^{-19}~\text{J}\); \(1~\text{MeV} = 10^6~\text{eV}\). These are vital when translating between reactor-scale energies and particle-scale interactions.

In practical design work you often compute a mass defect \(\Delta m\) from tabulated nuclear masses, then use \( E = \Delta m c^2 \) to estimate the energy release before moving into detailed thermal-hydraulic and shielding calculations.

How mass–energy equivalence connects rest mass and energy

The mass–energy equivalence equation emerges from special relativity. When you analyze how energy and momentum transform between observers moving at constant velocity relative to each other, you find that the total energy of a particle with rest mass \(m\) and speed \(v\) is

Here, \( \gamma \) is the Lorentz factor. When the particle is at rest relative to you (\( v = 0 \)), \(\gamma = 1\) and you recover the famous rest-energy relation \( E_0 = m c^2 \). The key insight is that even a stationary mass carries an enormous amount of energy “locked up” in its very existence.

From rest energy to usable energy: the role of mass defect

Engineering problems rarely convert the entire mass of a macroscopic object into energy. Instead, you deal with mass defects that show up when bound systems form or transform. A classic example is a nucleus: the mass of a bound nucleus is slightly less than the sum of the free protons and neutrons. That missing mass is the binding energy, and it is given by:

In nuclear fission and fusion, differences in binding energy per nucleon between initial and final nuclei produce the net energy release. When a heavy nucleus splits into intermediate-mass fragments, or when light nuclei fuse into more tightly bound products, the mass difference translates directly into heat and radiation through \( E = \Delta m c^2 \).

Dimensional checks & scale of energies

A quick dimensional check confirms that the equation is consistent in SI units. Mass has units of kilograms, and the speed of light squared has units of \( \text{m}^2/\text{s}^2 \):

The sheer size of \(c^2\) explains why even tiny mass defects matter. Using the convenient approximation \( c \approx 3.00 \times 10^8~\text{m/s} \), you get:

So \(1~\text{kg}\) of mass corresponds to about \(9 \times 10^{16}~\text{J}\) of energy. Even converting a gram of mass (\(10^{-3}~\text{kg}\)) entirely into energy would yield \(9 \times 10^{13}~\text{J}\), far exceeding the chemical energy in many thousands of tons of conventional fuel. Actual reactors convert only small fractions of the available rest energy, but these numbers illustrate why nuclear energy is so dense compared to chemical sources.

In high-speed regimes, you use the full relativistic energy formula rather than just \( E_0 = m c^2 \), but the algebra still respects the same mass–energy bookkeeping. Differences in total energy between states correspond to work done, radiation emitted, or kinetic energy gained, all ultimately anchored by the mass–energy equivalence principle.

Worked examples using the mass–energy equivalence equation

The following examples mirror common questions students and engineers ask: how much energy corresponds to a given mass, how to handle mass defect in nuclear reactions, and how to translate between joules and MeV. Use them as patterns whenever you need to apply \( E = m c^2 \) in design or analysis.

Example 1 – Energy equivalent of 1 gram of mass

Suppose, as a thought experiment, that you could convert exactly \(1.00~\text{g}\) of mass completely into energy. How much energy would this represent in joules, and what is that approximately equivalent to in kWh?

- Convert the mass into kilograms.

- Apply \( E = m c^2 \) using \( c \approx 3.00 \times 10^8~\text{m/s} \).

- Convert the resulting energy from joules to kilowatt-hours.

Result: Fully converting just 1 gram of mass into energy would yield about \(9 \times 10^{13}~\text{J}\), or roughly \(25\) million kWh. That is comparable to the annual electrical consumption of thousands of typical homes, illustrating the enormous energy density implied by \( E = m c^2 \).

Example 2 – Binding energy from nuclear mass defect

A simplified model of a helium-4 nucleus (\(^4\text{He}\)) uses the following atomic masses: mass of a proton \(m_p = 1.0073~\text{u}\), mass of a neutron \(m_n = 1.0087~\text{u}\), and mass of the \(^4\text{He}\) nucleus \(m_{\text{He}} = 4.0015~\text{u}\). Estimate the binding energy of \(^4\text{He}\) in MeV using \( E = \Delta m c^2 \) and the conversion \( 1~\text{u} \approx 931.5~\text{MeV}/c^2 \).

- Compute the sum of the free nucleon masses (2 protons + 2 neutrons).

- Find the mass defect \(\Delta m\) as the difference between this sum and the actual nuclear mass.

- Convert the mass defect in atomic mass units to MeV using the given conversion factor.

Result: The helium-4 nucleus has a binding energy of roughly \(28~\text{MeV}\). This energy is what would need to be supplied to completely separate the nucleus into free protons and neutrons, and it arises directly from the small mass defect via \( E = \Delta m c^2 \).

Example 3 – Electron–positron annihilation energy

An electron and a positron (its antimatter counterpart) each have a rest mass of approximately \( m_e = 9.11 \times 10^{-31}~\text{kg} \). When they annihilate at rest, their entire rest mass converts into photon energy. How much energy is released in joules and in MeV?

- Compute the total mass of the electron–positron pair.

- Apply \( E = m c^2 \) with the combined mass.

- Convert from joules to MeV using \(1~\text{eV} \approx 1.602 \times 10^{-19}~\text{J}\).

Result: Annihilating an electron–positron pair at rest releases about \(1.6 \times 10^{-13}~\text{J}\), corresponding to approximately \(1.02~\text{MeV}\) of photon energy. This is a standard reference scale in particle physics detectors and medical imaging systems such as PET scanners.

Design tips, limitations & sanity checks for \( E = m c^2 \)

While \( E = m c^2 \) is iconic, in engineering you use it in specific, well-defined contexts rather than as a catch-all formula for any energy change. The following notes highlight when the equation is most useful, what assumptions you are making, and how to check that your results are realistic.

- Nuclear fission and fusion calculations where mass defects between reactants and products are tabulated or measured.

- Particle physics problems involving rest energies, thresholds for particle creation, or annihilation processes.

- High-energy astrophysics (supernovae, neutron stars, black holes), where extreme gravitational binding energies and relativistic speeds appear.

- Assuming all of a fuel’s mass is converted to energy; in real reactors only a small fraction of the rest energy becomes usable output.

- Using \( E = m c^2 \) to estimate chemical reaction energies; here, mass defects are tiny and thermodynamics is better handled with enthalpies and Gibbs energies.

- Ignoring the difference between rest energy and total energy at relativistic speeds. For fast particles, use the full \( E = \gamma m c^2 \) relation rather than just \(m c^2\).

Because \(c^2\) is so large, it is easy to make order-of-magnitude errors. Before finalizing a design or report, run through a few sanity checks:

- Confirm your mass inputs are realistic (e.g., grams vs kilograms, atomic mass units vs kilograms).

- Check unit conversions carefully, especially between joules and eV/MeV; powers of 10 errors are common.

- Compare your computed energy against context: reactor power ratings, explosive yields, or stellar luminosities, depending on the problem scale.

In many engineering workflows, \( E = \Delta m c^2 \) is just the first step. Once you know how much energy is theoretically available or released, you still need to model how it appears (gamma rays, kinetic energy of fragments, heat), how efficiently your system can capture it, and what structures are required to contain and convert it safely.

Mass–energy equivalence equation – FAQ

What does the mass–energy equivalence equation mean in simple terms?

In plain language, \( E = m c^2 \) says that mass and energy are two faces of the same coin. Any object with mass has an enormous amount of “built-in” energy, and small changes in mass can correspond to very large changes in energy. In most everyday situations this energy is not accessible, but in nuclear and high-energy processes the mass difference between reactants and products shows up as heat, radiation, or kinetic energy.

How do I actually use \( E = m c^2 \) in engineering problems?

The most common workflow is: (1) determine the mass defect \(\Delta m\) between initial and final states using tabulated masses or measurements; (2) convert \(\Delta m\) into consistent units (kg or atomic mass units); (3) apply \( E = \Delta m c^2 \) to get the corresponding energy; and (4) translate that energy into reactor power, particle energies, or other design-level quantities. For micro-scale particle problems, you often work directly in MeV using the shortcut \(1~\text{u} \approx 931.5~\text{MeV}/c^2\).

Does \( E = m c^2 \) apply to chemical reactions?

Strictly speaking, mass–energy equivalence applies to all processes, including chemical reactions, but the mass changes in chemistry are so tiny that they are usually undetectable. For chemical engineering and thermodynamics, it is far more practical to use enthalpy and Gibbs free energy from tables rather than trying to track minuscule mass defects via \( E = m c^2 \). The equation becomes essential when dealing with nuclear or relativistic processes where the mass differences are much larger in relative terms.

What is the difference between \( E = m c^2 \) and \( E = \gamma m c^2 \)?

\( E = m c^2 \) refers specifically to the rest energy of a body, measured in a frame where the body is not moving. The more general relation \( E = \gamma m c^2 \) includes kinetic energy when the body moves at a significant fraction of the speed of light, with \(\gamma\) capturing the relativistic effects. For most nuclear power and basic particle calculations focused on rest energies and mass defects, the rest-energy form is sufficient; for high-speed accelerator design or cosmic-ray physics, the full relativistic expression is required.

References & further reading

- Standard university texts on modern physics and nuclear engineering, which derive mass–energy equivalence from special relativity and apply it to fission, fusion, and radioactive decay.

- Introductory particle physics resources that treat rest mass, binding energy, and annihilation processes in terms of MeV and GeV scales.

- Technical reports and design guides for nuclear reactors, accelerators, and radiation facilities, where mass-defect energy calculations form the starting point for power and shielding design.