Structural Engineering · Euler’s Formula

Euler’s Formula – critical buckling load for slender columns explained

Euler’s column buckling formula gives the critical axial load at which a perfectly straight, slender, elastic column will suddenly buckle, setting an upper bound for safe compressive design of columns and struts.

Quick answer: what Euler’s Formula tells you about column buckling

Core formula (ideal elastic column)

Euler’s column buckling formula states that a perfectly straight, slender, elastic column will buckle suddenly when its axial compressive load reaches the critical value \( P_{\text{cr}} \), which depends on the material stiffness \(E\), the section stiffness \(I\), the effective length factor \(K\), and the column length \(L\).

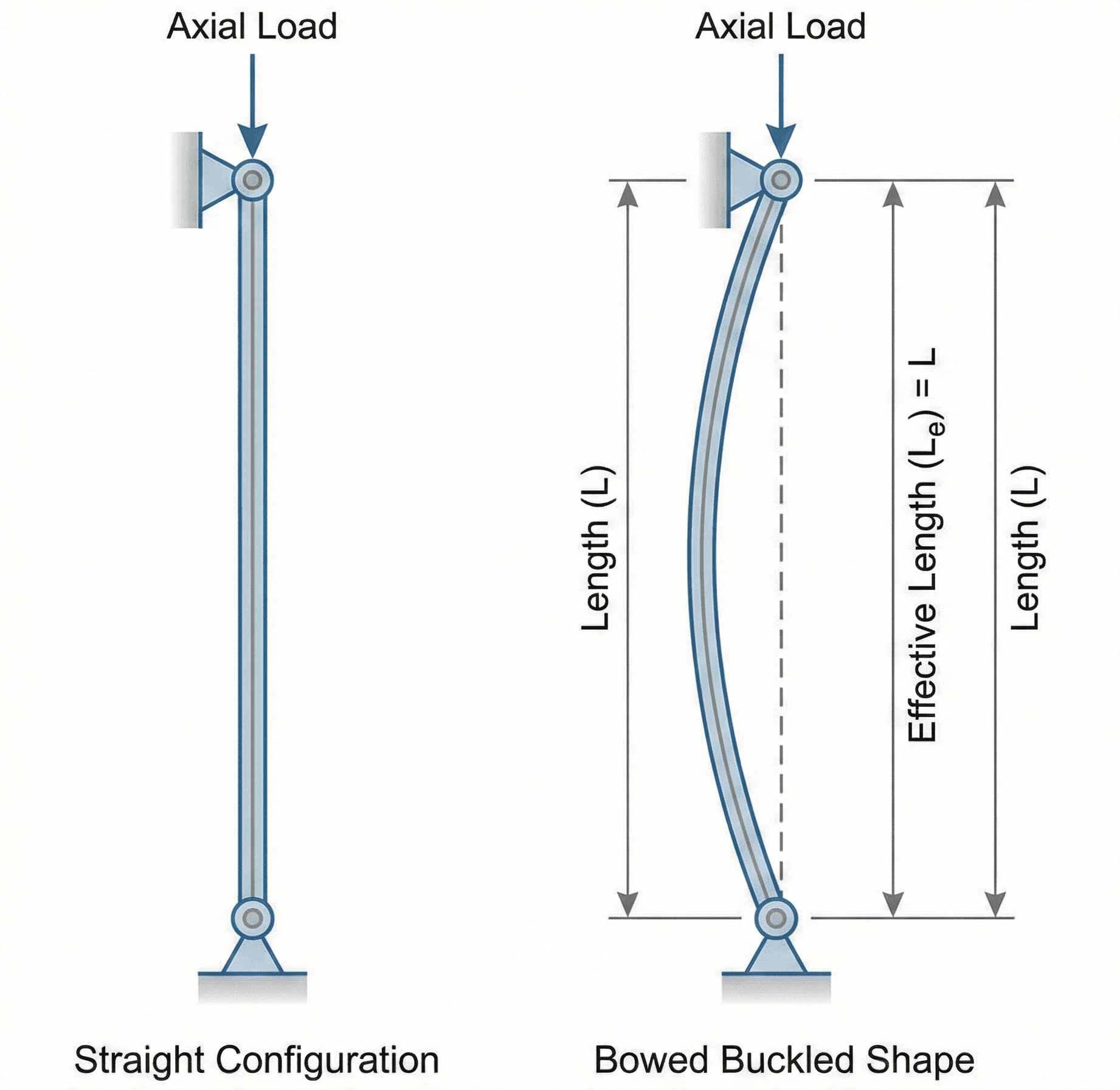

In structural engineering, many compression members – steel columns, truss members, masts, struts – fail not by crushing the material, but by suddenly bowing sideways. Euler’s Formula models this behavior for an idealized case: a straight, centrally loaded, prismatic column that remains in the elastic range and is free of initial crookedness or residual stresses. Under those assumptions, the buckling load \( P_{\text{cr}} \) marks the point where a perfectly straight configuration becomes unstable.

The effective length factor \(K\) captures how restraining the end conditions are. A pinned–pinned column has \(K = 1.0\), a fixed–fixed column behaves shorter with \(K \approx 0.5\), and a cantilever (fixed–free) is more flexible with \(K \approx 2.0\). For the same cross-section and material, tighter end restraints (smaller \(K\)) raise the buckling load dramatically. As you will see in the worked examples, small changes in \(K\) or length can produce very large changes in \(P_{\text{cr}}\).

In design, Euler’s Formula is rarely the final answer by itself. Codes typically blend the Euler curve with inelastic and yield-based curves, and apply safety and resistance factors. But it still provides the elastic upper bound on what any long, slender column can safely carry and is the backbone for many column design curves and interaction formulas.

Symbols, units & slenderness terms in Euler’s column formula

Euler’s buckling equation is usually written for an ideal prismatic column as \( P_{\text{cr}} = \pi^2 E I / (K L)^2 \). In design codes, you will also see it in terms of the slenderness ratio \( \lambda = K L / r \), where \( r = \sqrt{I/A} \) is the radius of gyration. The table below summarizes the main symbols and units you will use with the equation.

Common notation for Euler buckling

| Symbol | Quantity | SI Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( P_{\text{cr}} \) | Critical buckling load | Newton (N) | Maximum ideal elastic axial compressive load before buckling. In design, factored strengths are taken below this value. |

| \( E \) | Young’s modulus | Pa (N/m²) | Elastic stiffness of the material. Structural steel is typically \(E \approx 200~\text{GPa}\); aluminum is around 70 GPa. |

| \( I \) | Second moment of area | m⁴ | Flexural stiffness of the cross-section about the axis of buckling (usually the weak axis). Depends strongly on shape and size. |

| \( L \) | Actual column length | m | Center-to-center distance between bracing points along the buckling axis; the clear unbraced length for the column. |

| \( K \) | Effective length factor | – | Dimensionless factor representing end restraint conditions. Typical textbook values: 1.0 (pinned–pinned), 0.5 (fixed–fixed), 0.7 (fixed–pinned), 2.0 (fixed–free). |

| \( r \) | Radius of gyration | m | Section parameter defined by \( r = \sqrt{I/A} \). Measures how far area is distributed from the centroid. Used in slenderness ratio \( \lambda = K L / r \). |

| \( \lambda \) | Slenderness ratio | – | Non-dimensional measure of column slenderness. High \( \lambda \) (typically > 80–100) indicates Euler-type buckling dominates rather than material crushing. |

Unit system & practical notes

- In SI-based design, keep \(E\) in Pa (or GPa converted to Pa), \(I\) in m⁴, and \(L\) in m so that \(P_{\text{cr}}\) comes out in newtons. Converting midway is a common source of mistakes.

- In steel design, it is common to work in kN and mm: convert \(E\), \(I\), and \(L\) consistently so that units cancel correctly. Many engineers keep everything in N and mm and convert at the end.

- Always compute slenderness about the weak axis (smaller \(I\) and \(r\)). That axis usually controls buckling even if the strong-axis capacity looks comfortable.

Once the parameters are defined, you can explore different column lengths, shapes, and end conditions numerically using the column buckling calculator and quickly see how they affect the critical buckling load.

How Euler’s buckling formula emerges from elastic stability

The heart of Euler’s Formula is a stability analysis. Consider an initially straight column under axial compression. For very small loads, the straight configuration is stable – if you give it a tiny lateral perturbation, it springs back. At a certain critical load, however, that straight configuration becomes neutrally stable: a tiny perturbation no longer dies out but can grow into a sideways deflection. Solving the differential equation for the column at that neutral condition gives the familiar Euler load.

For a prismatic, pin-ended column of length \(L\) with flexural rigidity \(E I\), the lateral deflection \(y(x)\) under an axial load \(P\) satisfies the linearized differential equation

Non-trivial (non-zero) solutions exist when the load \(P\) takes on specific values that make the boundary-value problem have sine-shaped modes. For the fundamental buckling mode of a pin–pin column, that eigenvalue is

Other end conditions change the shape and effective half-wavelength of the buckling mode. Instead of re-deriving the differential equation every time, we capture that effect with the effective length factor \(K\), so the general Euler expression becomes

Slenderness ratio and when Euler’s curve is valid

Euler’s Formula assumes purely elastic behavior – the material stress at buckling is well below its yield strength. For a given cross-section, that requirement translates into a minimum slenderness ratio. Writing the critical stress as \( \sigma_{\text{cr}} = P_{\text{cr}}/A \) and using \( r = \sqrt{I/A} \), we obtain

For very large \( \lambda \), this stress is small compared to yield, and the Euler model is appropriate. As \( \lambda \) drops, \( \sigma_{\text{cr}} \) approaches or exceeds yield stress, and inelastic column curves or pure compression checks become more relevant. Many design codes define a limiting slenderness below which Euler’s Formula is not used directly but still influences the inelastic curves.

Effective length factors and end restraints

End restraints have a huge impact on buckling capacity. A column fixed against rotation and translation at both ends can carry several times the load of a pin–pin column of the same physical length. Rather than recomputing mode shapes, engineers use tabulated effective length factors \(K\) to represent these changes.

Textbook values assume idealized restraints; real frames fall somewhere between. Modern steel codes provide alignment charts or equations to estimate effective length based on frame stiffness and end conditions. When stiffness is uncertain, erring on the side of a larger \(K\) (longer effective length) is conservative.

In summary, Euler’s Formula captures the first elastic instability of an ideal column. In practice it is blended with material yielding, residual stresses, out-of-straightness and frame interaction, but the underlying \( \pi^2 E I / (K L)^2 \) relationship still governs the shape of most column design curves and the trends you see in the design checks and limitations.

Worked examples using Euler’s column buckling formula

These examples show how to apply Euler’s Formula to real-but-simplified situations: finding the critical load for a given column, solving for maximum unbraced length, and comparing different end conditions. In each case, keep in mind that codes will require additional reductions and safety factors beyond the raw Euler value.

Example 1 – Critical buckling load of a pinned–pinned steel column

A structural steel column is 4.0 m long between pinned supports and is likely to buckle about its weak axis. About that axis, the second moment of area is \( I = 8.0 \times 10^{-6}~\text{m}^4 \). Assume \(E = 200~\text{GPa}\) and ideal pin–pin behavior. Estimate the Euler critical buckling load.

- Identify end conditions and select the effective length factor \(K\).

- Convert material properties to consistent SI units.

- Apply \( P_{\text{cr}} = \pi^2 E I / (K L)^2 \).

Result: The ideal elastic critical load for this pinned–pinned column is roughly \( P_{\text{cr}} \approx 990~\text{kN} \). In practice, design strengths would be taken well below this to account for imperfections, residual stresses and code-required resistance factors.

Example 2 – Maximum unbraced length for a target axial load

You need a steel column to carry a factored axial compression of 400 kN. You want the elastic Euler load to be at least 2.5 times this value as a preliminary check, so \( P_{\text{cr}} \geq 1{,}000~\text{kN} \). The cross-section and buckling axis give \( I = 1.2 \times 10^{-5}~\text{m}^4 \), with \(E = 200~\text{GPa}\). The column is approximately fixed at the base and pinned at the top, so use \( K = 0.7 \). What is the maximum unbraced length \(L_{\max}\) that meets this target?

- Set the Euler load equal to the target minimum and solve for effective length \(K L\).

- Back out the actual length \(L_{\max}\) from \(K L\).

- Interpret the result in terms of bracing layout.

Result: The unbraced length should be limited to about \(7~\text{m}\) or less to keep the Euler load at least 2.5 times the design compression. In practice, you would choose a slightly shorter bracing spacing or a stiffer section to allow for uncertainties in end fixity and code-based reductions.

Example 3 – Comparing end conditions for the same physical column

A 3.0 m long aluminum tube is used as a compression member in two different applications. For both, \(E = 70~\text{GPa}\) and \( I = 3.5 \times 10^{-6}~\text{m}^4 \) about the relevant axis. In case A, the member is approximately pinned–pinned. In case B, both ends are effectively fixed. Estimate the ratio of critical buckling loads between the two cases using Euler’s Formula.

- Assign effective length factors \(K_A\) and \(K_B\) for the two end conditions.

- Write Euler’s Formula for each case and form the ratio \(P_{\text{cr,B}} / P_{\text{cr,A}}\).

- Simplify, noting that \(E\), \(I\), and \(L\) are the same in both cases.

Result: The fixed–fixed column (case B) can theoretically carry four times the Euler buckling load of the pinned–pinned column (case A) with the same length and cross-section. In real structures, perfectly fixed ends are rare, but this example shows why improving end restraint or adding bracing can be far more efficient than simply making the member heavier.

Design tips, limits & checks when using Euler’s Formula

Euler’s buckling formula is powerful but idealized. Using it directly for real columns without understanding its assumptions can lead to unconservative designs. This section highlights practical tips, common pitfalls, and quick checks that pair well with code provisions and the more detailed guidance you will find in specifications.

The most important judgment is whether the column is slender enough that Euler-type behavior governs. If slenderness is low, material yielding and inelastic buckling will control instead.

- Compute \( \lambda = K L / r \). For many steels, \( \lambda \gtrsim 100 \) clearly indicates Euler-like behavior.

- Compare the Euler critical stress \( \sigma_{\text{cr}} = \pi^2 E / \lambda^2 \) to yield stress. If \( \sigma_{\text{cr}} \ll f_y \), Euler is appropriate.

- If \( \sigma_{\text{cr}} \) is near or above yield, switch to inelastic or short-column design formulas rather than pure Euler theory.

Real columns are never perfectly straight and never perfectly pinned or fixed. Initial crookedness, residual stress and load eccentricity all reduce the load at which significant lateral deflections occur.

- Use realistic or slightly conservative \(K\) values rather than best-case ones, especially in flexible frames.

- Account for imperfections by using design curves or \(\phi\)- and \(\gamma\)-factors from your code instead of raw Euler loads.

- If your Euler-based estimate suggests you are close to capacity, refine the model or consult code interaction equations before finalizing the design, and revisit the assumptions in the FAQ on limitations.

Column calculations are prone to unit and axis mix-ups. A few quick habits can prevent major errors.

- Work in a consistent set of units – for example, N–m–Pa or kN–mm–MPa – and convert once at the end.

- Make it explicit which axis you are checking (strong vs. weak); the weaker axis usually controls buckling.

- If the member is part of a frame, consider whether sway or non-sway buckling modes might change the effective length and capacity.

Modern design codes blend Euler theory with empirical and inelastic effects, but understanding the underlying \( \pi^2 E I / (K L)^2 \) relationship helps you sanity-check code outputs, spot overly slender members early, and communicate design decisions clearly to reviewers and colleagues.

Euler’s Formula – frequently asked questions

What is Euler’s Formula for column buckling in simple terms?

For columns, Euler’s Formula says that a long, slender, perfectly straight column made of an elastic material will suddenly buckle sideways when the compressive load reaches \( P_{\text{cr}} = \pi^2 E I / (K L)^2 \). The stiffer the material and the cross-section (large \(E I\)), and the shorter the effective length \(K L\), the higher the load the column can carry before buckling.

When can I safely use Euler’s buckling formula in design?

You can use Euler’s Formula as a good approximation when the column is slender, the material remains elastic at buckling, and the load is applied concentrically through the centroid. In practice, design codes define slenderness limits and provide column curves that are based on, but more conservative than, the pure Euler line. Use those code formulas for final design, and use Euler’s equation for quick checks, trend analysis and sanity checks on the order of magnitude of capacities.

What is the difference between Euler’s column formula and Euler’s formula \( e^{i\theta} = \cos\theta + i\sin\theta \)?

The phrase “Euler’s Formula” can refer to two different equations named after Leonhard Euler. In structural engineering, it almost always means the column buckling formula \( P_{\text{cr}} = \pi^2 E I / (K L)^2 \). In complex analysis, “Euler’s formula” usually refers to \( e^{i\theta} = \cos\theta + i\sin\theta \), which relates complex exponentials to sines and cosines. Context – columns versus complex numbers – tells you which one is meant.

Why is my Euler buckling capacity higher than the design capacity from the code?

Raw Euler calculations ignore residual stresses, initial crookedness, load eccentricity, local buckling and uncertainties in end fixity. Modern steel and concrete codes fold those effects into reduced design curves, safety factors and resistance factors, so code-based capacities will be lower than Euler’s ideal value. This difference is expected and is one reason Euler’s Formula is best viewed as an upper bound and a conceptual tool rather than a stand-alone design check.

References & further reading

- Standard structural analysis and stability textbooks covering elastic column buckling, effective length factors and the derivation of Euler’s critical load.

- Steel and concrete design specifications and commentaries, which provide column design curves derived from Euler theory but modified for inelastic behavior and imperfections.

- Design guides and technical notes from structural engineering societies that include worked examples of column slenderness checks and buckling calculations.