Fluid Mechanics · Bernoulli’s Equation

Bernoulli’s Equation – pressure, velocity & elevation in incompressible flow

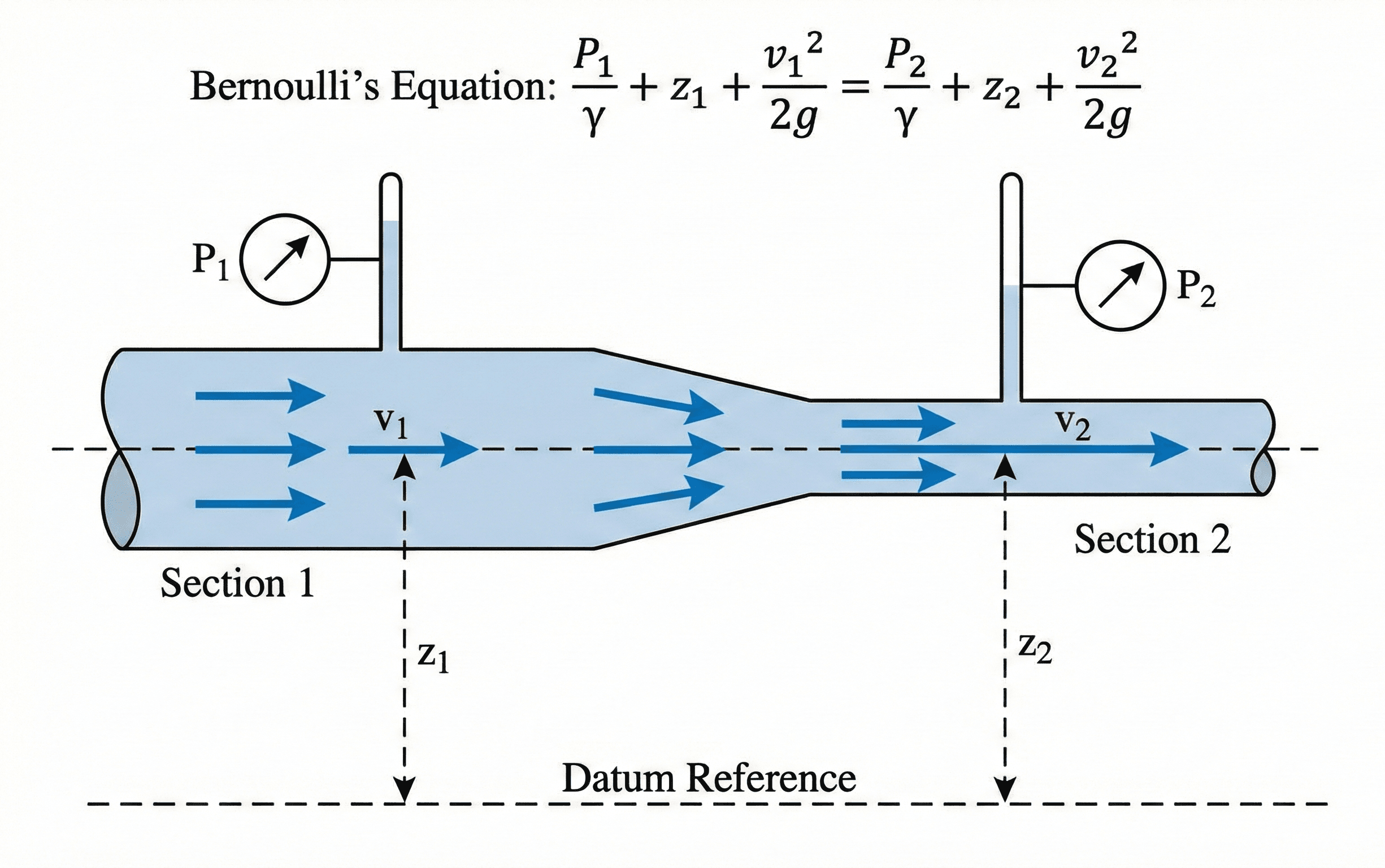

Bernoulli’s Equation expresses how pressure, velocity, and elevation trade off along a streamline in steady, incompressible flow, giving you a practical energy balance for sizing pipes, nozzles, and flow meters.

Quick answer: what Bernoulli’s Equation tells you

Core formula (head form, along a streamline)

Bernoulli’s Equation says that for steady, incompressible, inviscid flow along a streamline, the sum of pressure head, velocity head, and elevation head stays constant – so if the fluid speeds up, pressure or elevation must drop to pay for that extra kinetic energy.

In practical fluid mechanics, Bernoulli’s Equation is the go-to energy balance for single-phase liquids moving through relatively smooth piping and simple fittings. It connects the three most important pieces of the puzzle – pressure, velocity, and elevation – so you can answer questions like “What pressure drop is caused by this nozzle?”, “How fast is fluid moving if my pressure taps read this difference?”, or “What happens to pressure if I route the line higher than the tank?”.

The version you see first, \( \tfrac{P}{\rho g} + \tfrac{v^2}{2g} + z = \text{constant} \), is a simplified form of a more general mechanical energy equation. In that idealized setting there are no pumps adding energy, no turbines extracting it, and no viscous head losses. Real engineering systems almost always need those extra terms, but the core Bernoulli balance gives you the backbone: it tells you how energy would redistribute along a streamline if there were no losses, and it remains embedded in more complete head-loss and pump-sizing equations you will use in design.

As you’ll see in the worked examples, Bernoulli’s Equation shows up any time you have pressure taps, manometers, or differential pressure transmitters on a line and want to translate those readings into velocities, flow rates, or elevation changes. It is also one of the first equations students use to connect textbook conservation laws with what a gauge actually reads on a real piece of hardware.

Symbols, units & notation in Bernoulli’s Equation

In its most common form for incompressible flow along a streamline, Bernoulli’s Equation can be written as \( \tfrac{P}{\rho g} + \tfrac{v^2}{2 g} + z = \text{constant} \) or, between two specific points 1 and 2,

Each term represents energy per unit weight of fluid (a “head” term). The table below summarizes the most common symbols, units, and interpretations you’ll use when applying Bernoulli’s Equation to pipes and open-channel flows.

Common Bernoulli notation

| Symbol | Quantity | Typical SI unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( P \) | Static pressure | Pa (N/m²) | Thermodynamic pressure in the fluid. In Bernoulli’s Equation you typically use gauge pressure so that atmospheric pressure cancels when both points are open to the atmosphere. |

| \( v \) | Average velocity | m/s | Mean flow velocity at a cross-section, defined from volumetric flow rate \(Q\) as \( v = Q / A \), where \(A\) is the cross-sectional area normal to the flow. |

| \( z \) | Elevation head | m | Height of the point above a chosen datum. Represents potential energy per unit weight, \(z = \text{PE}/(\text{weight})\). |

| \( \rho \) | Density | kg/m³ | Fluid mass per unit volume. For water at room temperature, \( \rho \approx 1000~\text{kg/m}^3 \); for light oils and other liquids it is usually lower. |

| \( g \) | Acceleration due to gravity | m/s² | Standard gravitational acceleration, \( g \approx 9.81~\text{m/s}^2 \). Appears when writing energy per unit weight or “head.” |

| \( \gamma \) | Specific weight | N/m³ | Defined as \( \gamma = \rho g \). An alternative form of Bernoulli’s Equation often uses \( \tfrac{P}{\gamma} \) instead of \( \tfrac{P}{\rho g} \) for pressure head. |

| \( h_L \) | Head loss | m | Energy loss per unit weight due to friction and fittings. Not present in the ideal Bernoulli equation but included in extended energy equations, for example \( \tfrac{P_1}{\gamma} + \tfrac{v_1^2}{2g} + z_1 = \tfrac{P_2}{\gamma} + \tfrac{v_2^2}{2g} + z_2 + h_L \). |

Unit systems & practical notes

- In SI calculations, head terms are in meters. For example, \( \tfrac{P}{\rho g} \) has units of meters when \(P\) is in Pa, \(\rho\) in kg/m³, and \(g\) in m/s².

- In U.S. customary units, you must be careful with lbm, lbf, and ft/s². Texts often introduce consistent sets (like gc) so that Bernoulli’s Equation still produces head in feet.

- Pressure in Bernoulli problems is usually gauge pressure when both points are exposed to the same atmosphere, because the atmospheric term cancels between the two sides.

Once you are comfortable with the symbols and units, you can plug real numbers into Bernoulli’s Equation by hand or use a dedicated tool like the Bernoulli’s Equation calculator to experiment with different pressures, velocities, and elevation differences in a pipe system.

How Bernoulli’s Equation expresses fluid energy

At its core, Bernoulli’s Equation is a statement of mechanical energy conservation for a flowing fluid. If you follow a tiny packet of liquid along a streamline in steady flow, the sum of its pressure energy, kinetic energy, and potential energy stays constant – provided there is no shaft work added or removed and no significant viscous dissipation. This leads directly to the familiar “head” balance used in water distribution, HVAC, and many other systems.

From the energy equation to Bernoulli’s head form

A more general steady-flow energy equation for incompressible, single-phase flow can be written (per unit weight of fluid) as

Here \(h_{\text{pump}}\) is head added by a pump, \(h_{\text{turbine}}\) is head extracted by a turbine, and \(h_L\) represents head loss due to friction and fittings between 1 and 2. If we consider a situation with no pumps, no turbines, and negligible head loss between our two points, the extra terms drop out and we recover the ideal Bernoulli relation:

This is why Bernoulli’s Equation is sometimes described as the “frictionless” or “lossless” energy equation. In real pipes you bring back \(h_L\) and sometimes pump terms, but those are added on top of the Bernoulli structure, not instead of it.

Static, dynamic & elevation pressure

Engineers often interpret Bernoulli’s Equation in terms of three contributions to the total head:

Pressure head corresponds to how high a column of fluid would rise in a piezometer. Velocity head is the extra head associated with the fluid’s motion; it becomes especially important in nozzles and orifices. Elevation head captures gravitational potential energy. When flow accelerates through a constriction, velocity head increases, so one or both of the other contributions must decrease – usually pressure head drops, which you see as a lower static pressure in the smaller section.

This decomposition also explains stagnation pressure. If you bring a moving fluid packet to rest isentropically (for example at a stagnation point), all the velocity head is converted into pressure head, giving a higher local pressure. Many flow instruments are based on measuring the difference between static and stagnation pressure and then applying Bernoulli and continuity to recover velocity.

When Bernoulli’s Equation is a good approximation

Bernoulli’s Equation is not a universal law; it is a powerful approximation under certain conditions:

- Steady flow – properties at a point do not change significantly with time.

- Incompressible fluid – density is essentially constant (good for most liquids at moderate pressures).

- Negligible viscous effects along the streamline segment – no major separation or large friction losses over the distance considered.

- Application along a single streamline (or regions where the flow field is nearly uniform across the section).

If these conditions fail badly – for example in highly viscous, turbulent, or separated flows; in long rough pipes; or in high-speed compressible gas flows – then using a bare Bernoulli equation will give poor predictions. In such cases you either add head-loss correlations to the energy equation or move to more advanced analysis based on the Navier–Stokes equations and empirical data.

Worked examples using Bernoulli’s Equation

These examples mirror common homework and design questions: pressure change through a contraction, jet velocity from a tank, and flow rate through a venturi meter. Each follows the same pattern: define points 1 and 2, write continuity to relate velocities, then apply Bernoulli along a streamline and solve.

Example 1 – Pressure drop in a horizontal pipe contraction

Water at 20 °C flows steadily through a horizontal pipe that contracts from a diameter of 100 mm to 50 mm. The average velocity in the larger section is \( v_1 = 1.5~\text{m/s} \) and the static pressure there is \( P_1 = 250~\text{kPa (gauge)} \). Assuming negligible head loss between sections and incompressible flow, estimate the static pressure \( P_2 \) in the smaller section.

- Define sections 1 (upstream, large diameter) and 2 (downstream, small diameter); note that \(z_1 = z_2\) since the pipe is horizontal.

- Apply continuity to find \( v_2 \) from the area ratio.

- Apply Bernoulli between 1 and 2 to solve for \( P_2 \).

Result: The static pressure drops from about 250 kPa to about 233 kPa as the flow accelerates through the contraction. In reality, additional minor losses would cause a slightly larger pressure drop than the ideal Bernoulli prediction.

Example 2 – Jet velocity from a large tank (Torricelli’s law)

A large open tank is filled with water. There is a small sharp-edged orifice in the sidewall located 5 m below the free surface. Assuming the tank is wide enough that the liquid surface velocity is negligible and friction losses are small, estimate the jet velocity \( v_2 \) at the orifice exit.

- Take point 1 at the free surface and point 2 at the orifice exit, both exposed to atmospheric pressure.

- Set \( v_1 \approx 0 \) because the tank surface moves very slowly compared to the jet.

- Apply Bernoulli between 1 and 2 to solve for \( v_2 \).

Result: The ideal jet velocity is about \(9.9~\text{m/s}\). This is the classic Torricelli result. Real discharge velocities are slightly lower due to contraction and friction at the orifice, which is often captured by a discharge coefficient applied to the ideal Bernoulli prediction.

Example 3 – Flow rate from a venturi meter pressure difference

A horizontal venturi meter is installed in a water pipeline. The upstream diameter is 150 mm and the throat diameter is 75 mm. A differential pressure transmitter measures a steady pressure difference of \( \Delta P = P_1 – P_2 = 18~\text{kPa} \) between the upstream section and the throat. Neglecting head loss between taps and assuming incompressible flow, estimate the volumetric flow rate \(Q\).

- Use continuity to relate velocities \( v_1 \) and \( v_2 \) to diameters.

- Apply Bernoulli between upstream and throat to derive an expression for \( v_2 \) in terms of \( \Delta P \).

- Compute \( v_2 \) numerically, then find flow rate \(Q = A_2 v_2\).

Result: The ideal volumetric flow rate is about \(0.027~\text{m}^3/\text{s}\) (27 L/s). In real meters, a discharge coefficient less than 1.0 would be applied to account for losses and non-ideal velocity profiles, but the Bernoulli-based expression above is the starting point for those calibrations.

Design tips, limits & checks when using Bernoulli’s Equation

Bernoulli’s Equation is extremely powerful, but it is also one of the most commonly misapplied formulas in fluid mechanics. In design work you rarely use it alone; you combine it with continuity, head-loss correlations, pump curves, and sometimes empirical coefficients. The cards below highlight assumptions, pitfalls, and quick checks that help keep your Bernoulli-based calculations realistic.

Before trusting results, confirm that the scenario actually fits the Bernoulli picture. If not, you may still use a modified energy equation, but the simple “constant total head” idea will not hold.

- Incompressible liquid: Bernoulli in its basic form assumes constant density. Good for water and most oils in piping; more limited for gases unless Mach numbers are very low.

- Steady flow: The equation is derived under steady conditions; large transients (fast valve closures, water hammer) require separate unsteady analysis.

- Along a streamline: Strictly valid along a single streamline. Between two cross-sections with nearly uniform velocity, it works well when you pair it with an average velocity and continuity.

- Negligible viscous losses between points: Over long, rough, or heavily valved lengths of pipe, head losses must be included explicitly rather than ignored.

- Using Bernoulli between points where the flow is separated or recirculating (for example, just downstream of a sharp elbow), where the inviscid assumption is badly violated and head loss is large.

- Ignoring the continuity equation. Bernoulli alone cannot give you both pressures and velocities; you must also relate areas and flow rates so that mass is conserved.

- Mixing gauge and absolute pressures incorrectly, especially when one point is at the surface of a tank (where \(P\) is atmospheric) and the other is inside a pressurized line.

- Forgetting elevation differences in “horizontal-looking” systems, which can be significant over long runs or in tall buildings and storage tanks.

Even when your math is correct, it is good practice to sanity-check Bernoulli-based results before finalizing a design or troubleshooting conclusion.

- Compare predicted pressure drops with typical values from experience or references. If Bernoulli suggests almost no pressure change across a long, rough line, you probably need to include friction head using Darcy–Weisbach or Hazen–Williams.

- Check whether the Reynolds number indicates laminar, transitional, or turbulent flow. At very low Reynolds numbers, viscous effects dominate and pure Bernoulli is not appropriate.

- For flow meters (venturi, orifice, nozzle), confirm you are using the correct discharge coefficient and tapping arrangement; a bare Bernoulli prediction without these corrections will usually overpredict flow.

When the simple form is not adequate, you still keep the Bernoulli structure but add head-loss and pump terms, as in \( \tfrac{P_1}{\gamma} + \tfrac{v_1^2}{2g} + z_1 + h_{\text{pump}} = \tfrac{P_2}{\gamma} + \tfrac{v_2^2}{2g} + z_2 + h_L \). This extended equation is the workhorse for pump sizing, pipe network analysis, and many real-world design tasks.

Bernoulli’s Equation – FAQ

What is Bernoulli’s Equation in simple terms?

In simple language, Bernoulli’s Equation says that as a fluid speeds up, its static pressure or elevation (or both) must decrease so that the total energy per unit weight stays the same along a streamline. For steady, incompressible flow with no losses, the sum of pressure head, velocity head, and elevation head is constant. This is why a fluid in a narrower section of pipe tends to move faster and have lower static pressure than in a wider section.

When can I safely use Bernoulli’s Equation in engineering problems?

You can safely use Bernoulli’s Equation when the fluid is essentially incompressible (most liquids), the flow is steady, you are following a single streamline or a cross-section with reasonably uniform velocity, and viscous losses between your chosen points are small. It is well suited for short, smooth pipe segments, nozzles, venturi meters, and tank-orifice problems. For long pipe runs, highly viscous fluids, or strongly separated flows, you need to add friction and minor-loss terms to the energy balance.

How is Bernoulli’s Equation different from the continuity equation?

Bernoulli’s Equation is an energy balance: it relates pressure, velocity, and elevation. The continuity equation is a mass balance, stating that the same mass flow rate must pass through each cross-section for steady flow in a single-inlet, single-outlet system. In an incompressible pipe, continuity gives \( v_1 A_1 = v_2 A_2 \). In most problems you need both: continuity to relate velocities at different sections, and Bernoulli to connect those velocities to pressure and elevation changes.

How do I include friction losses or pumps in a Bernoulli-style calculation?

To include losses or added energy, you move from the pure Bernoulli equation to the more general energy equation. For example, \( \tfrac{P_1}{\gamma} + \tfrac{v_1^2}{2g} + z_1 + h_{\text{pump}} = \tfrac{P_2}{\gamma} + \tfrac{v_2^2}{2g} + z_2 + h_L \). Here \(h_{\text{pump}}\) is the head added by a pump and \(h_L\) is head loss due to friction and fittings, usually computed using correlations like Darcy–Weisbach and tabulated loss coefficients. The structure of Bernoulli is still visible; you have simply added extra terms to account for non-ideal effects.

References & further reading

- Standard fluid mechanics textbooks covering Bernoulli’s Equation, energy equations, and head-loss methods – for example, typical university-level “Fluid Mechanics” or “Applied Fluid Mechanics” texts.

- Manufacturer application notes and sizing guides for venturi meters, orifice plates, and nozzles, which show how Bernoulli-based formulas are combined with discharge coefficients and real-world calibration data.

- Open courseware lecture notes and problem sets from major universities, which provide additional worked examples and derivations of Bernoulli’s Equation and its limitations in both laminar and turbulent flow.