Mechanical Engineering · Newton’s Second Law

Newton’s Second Law – net force, mass & acceleration explained

Newton’s Second Law connects the net force on an object to its mass and resulting acceleration, giving you the core equation behind almost every dynamics, motion, and load-sizing calculation in engineering and physics.

Quick answer: what Newton’s Second Law tells you

Core formula

Newton’s Second Law states that the net force on a body equals its mass times its acceleration, so any change in motion comes directly from the vector sum of all forces acting on that body.

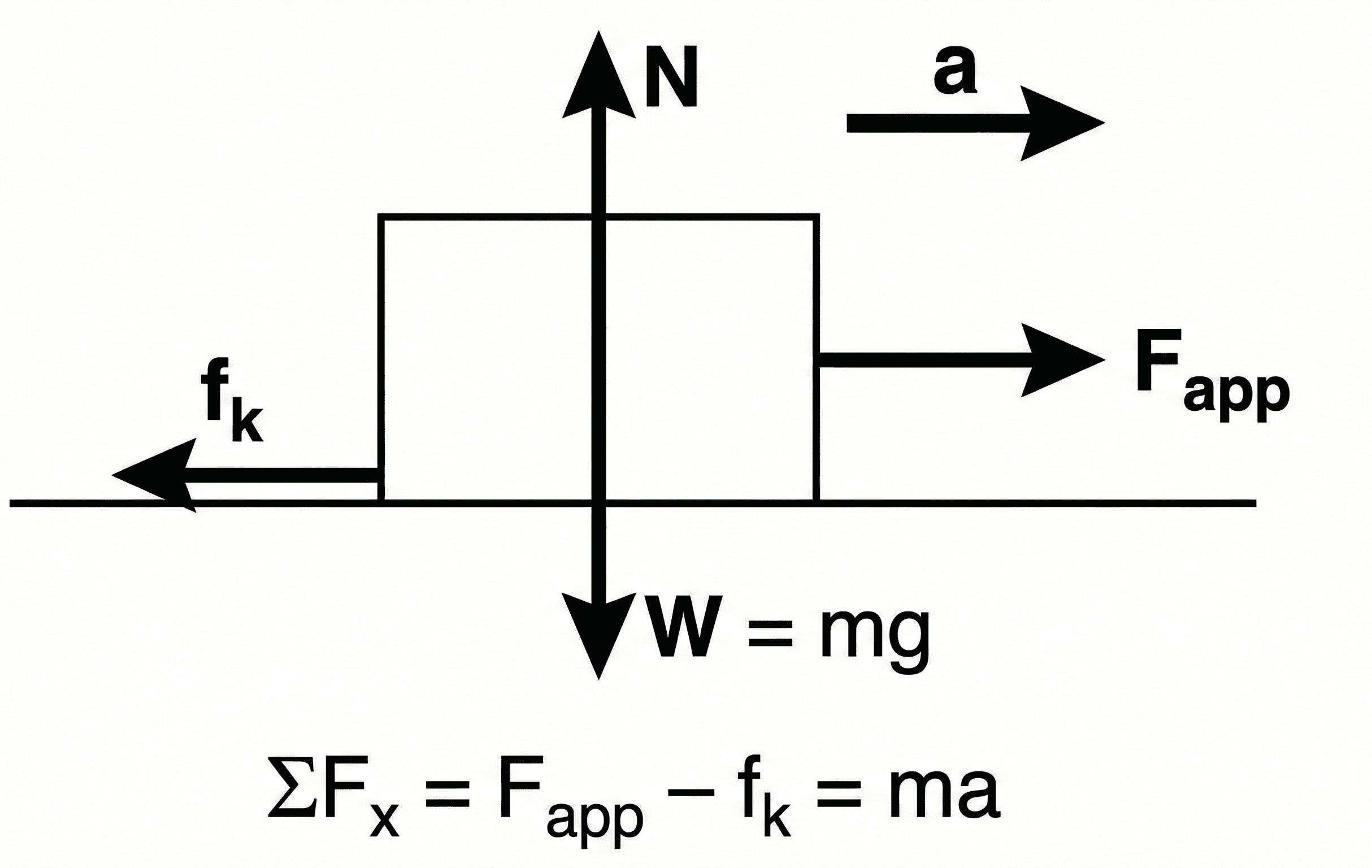

At the everyday engineering level, Newton’s Second Law is the workhorse of dynamics. Once you have a free-body diagram of all the forces on an object, you turn “arrows on a sketch” into equations using \( F_{\text{net}} = m a \). Along a given axis, the algebraic sum of forces equals the mass times the acceleration along that axis. If the net force is zero, acceleration is zero and the motion is uniform or at rest; if the net force is nonzero, the object speeds up, slows down, or changes direction.

This equation is vector-based and local: it applies separately in each direction, and it applies to each body you isolate. That’s why it shows up everywhere – from calculating the thrust needed for a drone to hover, to estimating the braking distance of a car, to checking whether a robotic arm motor is strong enough to accelerate a payload without stalling.

Symbols, units & notation in Newton’s Second Law

In introductory mechanics, Newton’s Second Law is usually written as \( \vec{F}_{\text{net}} = m \vec{a} \). For one-dimensional motion along an axis, you often drop the vector arrows and write \( \sum F = m a \). The table below summarizes the common symbols and engineering units used with this equation.

Common notation

| Symbol | Quantity | SI Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( \vec{F}_{\text{net}} \) | Net force | Newton (N) | Vector sum of all forces acting on a body along a given direction. \( 1~\text{N} = 1~\text{kg·m/s}^2 \). |

| \( m \) | Mass | Kilogram (kg) | Measure of inertia or “resistance to acceleration.” Assumed constant in standard Newton’s Second Law problems. |

| \( \vec{a} \) | Acceleration | m/s² | Rate of change of velocity with respect to time. Components can be written as \(a_x\), \(a_y\), \(a_z\). |

| \( W \) | Weight | Newton (N) | Gravitational force on a mass: \( W = m g \), with \( g \approx 9.81~\text{m/s}^2 \) near Earth’s surface. |

| \( \sum F_x \) | Net force in x | Newton (N) | Algebraic sum of force components along the x-axis; used in \( \sum F_x = m a_x \). |

Unit systems & practical notes

- SI (engineering standard): mass in kg, acceleration in m/s², forces in N. This keeps \(F = m a\) dimensionally clean and is preferred in professional work.

- Imperial / U.S. customary: beware of mixing pounds-force (lbf), pounds-mass (lbm), and slugs. Many errors come from skipping the conversion constants needed to keep \(F = m a\) consistent.

- Component form: always write separate equations along each axis, for example \( \sum F_x = m a_x \) and \( \sum F_y = m a_y \), rather than trying to treat everything as a single scalar equation.

Once your free-body diagram is set up and the symbols are clear, you can plug numbers into Newton’s Second Law by hand or use a dedicated tool like the Newton’s Second Law Calculator to quickly explore different force, mass, and acceleration combinations.

How Newton’s Second Law connects force and motion

Newton’s Second Law links cause and effect in mechanics. Forces are the “causes” coming from contact, gravity, springs, friction, or actuators. Acceleration is the “effect” – a change in velocity. The mass \(m\) of the object shows how stubborn it is about changing its motion. For a fixed net force, a larger mass accelerates less; for a fixed mass, a larger net force accelerates more.

The key word is net. Newton’s Second Law does not say that each individual force equals \( m a \). Instead, the vector sum of all forces – positive and negative contributions along each axis – equals \(m\) times the corresponding acceleration component. That’s why the law always goes hand in hand with a free-body diagram and equilibrium-style bookkeeping of forces, even when the motion is far from equilibrium.

Rearranging Newton’s Second Law & useful variants

Starting from \( \vec{F}_{\text{net}} = m \vec{a} \), you can rearrange the equation to solve for whichever quantity is unknown. In scalar form along a single axis, these are the most common versions:

In many engineering problems, you work component-wise:

You then combine these with kinematics equations (for example, constant-acceleration formulas for displacement and velocity) to fully describe a motion scenario – like a vehicle speeding up on a ramp or an elevator starting from rest.

Dimensional & sanity checks

Dimensional analysis is a quick way to verify that you’ve set up Newton’s Second Law correctly. In SI units, the dimensions line up as:

If your computed “force” comes out in kg·m/s or some other combination, something has gone wrong – often a missing time factor, a unit conversion mistake, or an incorrect interpretation of velocity vs. acceleration. A similar check is to estimate orders of magnitude: if a 1 kg object supposedly needs millions of newtons to accelerate gently, your free-body diagram or arithmetic probably needs another look.

Newton’s Second Law assumes an inertial reference frame (one not accelerating or rotating too wildly itself) and a constant mass. In rotating machinery, vehicles on curved paths, or systems with changing mass (like rockets), you extend the same core law with additional terms – but the underlying idea is unchanged: net interaction forces dictate how motion evolves over time.

Worked examples using Newton’s Second Law

The best way to internalize Newton’s Second Law is to walk through realistic problems. Each example below mirrors questions people actually search for and see in early dynamics courses: given forces and mass, find acceleration; given required acceleration, find the needed force; and given multiple forces, compute the net effect. You can adapt the same workflow to many other engineering situations.

Example 1 – Finding acceleration from a known net force

A 1,000 kg car experiences a total tractive force of 2,500 N in the forward direction (after accounting for rolling resistance and aerodynamic drag). Assuming the force is constant, what is the car’s acceleration, and how fast will it be moving after 8 seconds starting from rest?

- Write the scalar form of Newton’s Second Law along the direction of motion.

- Compute the acceleration from the net force and mass.

- Use constant-acceleration kinematics to find the final speed.

Result: The car accelerates at \(2.5~\text{m/s}^2\) and reaches a speed of \(20~\text{m/s}\) (about 72 km/h or 45 mph) after 8 seconds. This is a moderate but realistic acceleration for a passenger car under steady traction.

Example 2 – Required force for a target acceleration

You are sizing a linear actuator to accelerate a 50 kg machine table horizontally from rest to a speed of 0.6 m/s in 0.3 s, assuming roughly constant acceleration and neglecting friction for a first estimate. What average net force must the actuator provide along the direction of motion?

- Find the required acceleration from the desired change in velocity and time.

- Apply \( F_{\text{net}} = m a \) along the axis of motion.

- Interpret the result in terms of actuator selection and safety margin.

Result: The actuator must provide an average net force of around \(100~\text{N}\) along the direction of motion, on top of whatever is needed to overcome friction, guides, or cable forces. In practice, you would choose an actuator with a comfortable margin above this to account for losses and peak loads.

Example 3 – Multiple forces and friction on an incline

A 20 kg crate sits on a 25° rough incline. The coefficient of kinetic friction between the crate and the surface is \( \mu_k = 0.30 \). The crate is pulled up the incline by a rope with tension \(T = 120~\text{N}\). What is the acceleration of the crate along the incline (take up the slope as positive)?

The forces along the incline are: rope tension \(T\) (up the slope), component of weight \(m g \sin\theta\) (down the slope), and kinetic friction \(\mu_k N\) (also down the slope, opposing motion). First resolve the weight, then apply Newton’s Second Law along the incline.

Result: The negative sign means the acceleration is actually down the incline, with magnitude about \(0.81~\text{m/s}^2\). Even though you pull up the slope with 120 N, gravity and friction together are larger, so the crate slows if it was moving up, or speeds up down the slope if released. This is a classic example of why carefully summing all forces before applying Newton’s Second Law is essential.

Design tips, limits & checks when using Newton’s Second Law

In engineering design, Newton’s Second Law is rarely the whole story, but it is almost always the starting point. You combine it with material limits, actuator curves, friction models, and safety factors to make sure the accelerations you compute are realistic and safe. A few patterns show up again and again in practice.

Standard textbook problems quietly assume conditions that may not hold in a real machine or vehicle. Make sure these are reasonable before trusting a simple \( F = m a \) estimate.

- Mass of the body is constant in time and concentrated at a point (or treated via a rigid-body model).

- The reference frame is approximately inertial; large frame accelerations or rotations are handled separately.

- Forces are either constant or changed slowly enough that average values are meaningful over your time step.

- Setting each individual force equal to \( m a \) instead of the net force (forgetting to sum forces with signs).

- Mixing units (for example, kg with lbf) and getting accelerations that are off by factors of 9.81 or more.

- Ignoring friction, drag, or load dependence where they matter – leading to undersized actuators or unsafe braking distances.

Before committing to a design, run a few quick mental checks on your \( F = m a \) results.

- Compare accelerations to familiar values (for example, \(g \approx 9.81~\text{m/s}^2\)) – does the result seem physically plausible?

- Check that forces and resulting stresses stay within material and component ratings with a reasonable safety factor.

- If accelerations are very high, consider whether vibration, impact, or fatigue might dominate over static stress concerns.

When your system stretches beyond the simple constant-mass, low-speed regime – such as rockets burning fuel, vehicles cornering at high speed, or robots with flexible links – you still start from Newton’s Second Law, but in more advanced forms (often written as differential equations or expressed in matrix form for multi-degree-of-freedom systems). If your back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest you are close to critical limits, that is usually the cue to move beyond a single-axis \( F = m a \) model and into a more detailed simulation or finite-element analysis.

Newton’s Second Law – FAQ

What is Newton’s Second Law in simple terms?

In simple language, Newton’s Second Law says that how quickly an object speeds up or slows down depends on two things: how hard you push (the net force) and how heavy the object is (its mass). Push twice as hard on the same object and you double its acceleration; push the same amount on twice the mass and the acceleration halves. Mathematically, this is captured by \( F_{\text{net}} = m a \).

How do you actually use Newton’s Second Law to solve problems?

The standard workflow is: (1) draw a clear free-body diagram, isolating the object of interest; (2) resolve all forces into components along convenient axes; (3) write Newton’s Second Law along each axis (for example, \( \sum F_x = m a_x \)); (4) substitute known values and solve for the unknowns like acceleration, tension, or friction force. For many practical problems, you then combine these results with kinematics formulas to find velocities and displacements over time.

When does Newton’s Second Law not apply directly?

The textbook form \( F_{\text{net}} = m a \) assumes constant mass and an inertial reference frame. In cases with rapidly changing mass (rockets burning fuel), in strongly non-inertial frames (for example, inside a rapidly rotating carnival ride), or at relativistic speeds close to the speed of light, you need more general formulations. Even then, the idea that forces determine changes in motion remains central – the mathematics just becomes more elaborate.

Is weight the same thing as the “force” in Newton’s Second Law?

Weight is one specific force – the gravitational attraction between a mass and a planet – given by \( W = m g \). In Newton’s Second Law, \( F_{\text{net}} \) includes all forces: weight, normal reactions, friction, tension, drag, and applied loads. In some vertical-motion problems, the net force may be \( W – T \) or \( T – W \) depending on the sign convention, so it is important not to confuse “weight” with the “net force” that actually drives acceleration.

References & further reading

- Classical mechanics textbooks covering Newton’s laws of motion and engineering dynamics (for example, standard university-level “Engineering Mechanics: Dynamics” texts).

- Online lecture series and notes from major universities on introductory physics and dynamics, many of which include extensive Newton’s Second Law examples and problem sets.

- Application notes and design guides from actuator, robotics, and automotive manufacturers that walk through force, mass, and acceleration calculations in real-world systems.