Structural Engineering · Beam Deflection Formula

Beam Deflection Formula – stiffness, span & loading explained

The beam deflection formula links load, span, stiffness, and cross-section shape to how much a beam sags, helping you check serviceability and vibration long before strength becomes critical.

Quick answer: what the beam deflection formula tells you

Typical maximum deflection for a simple case

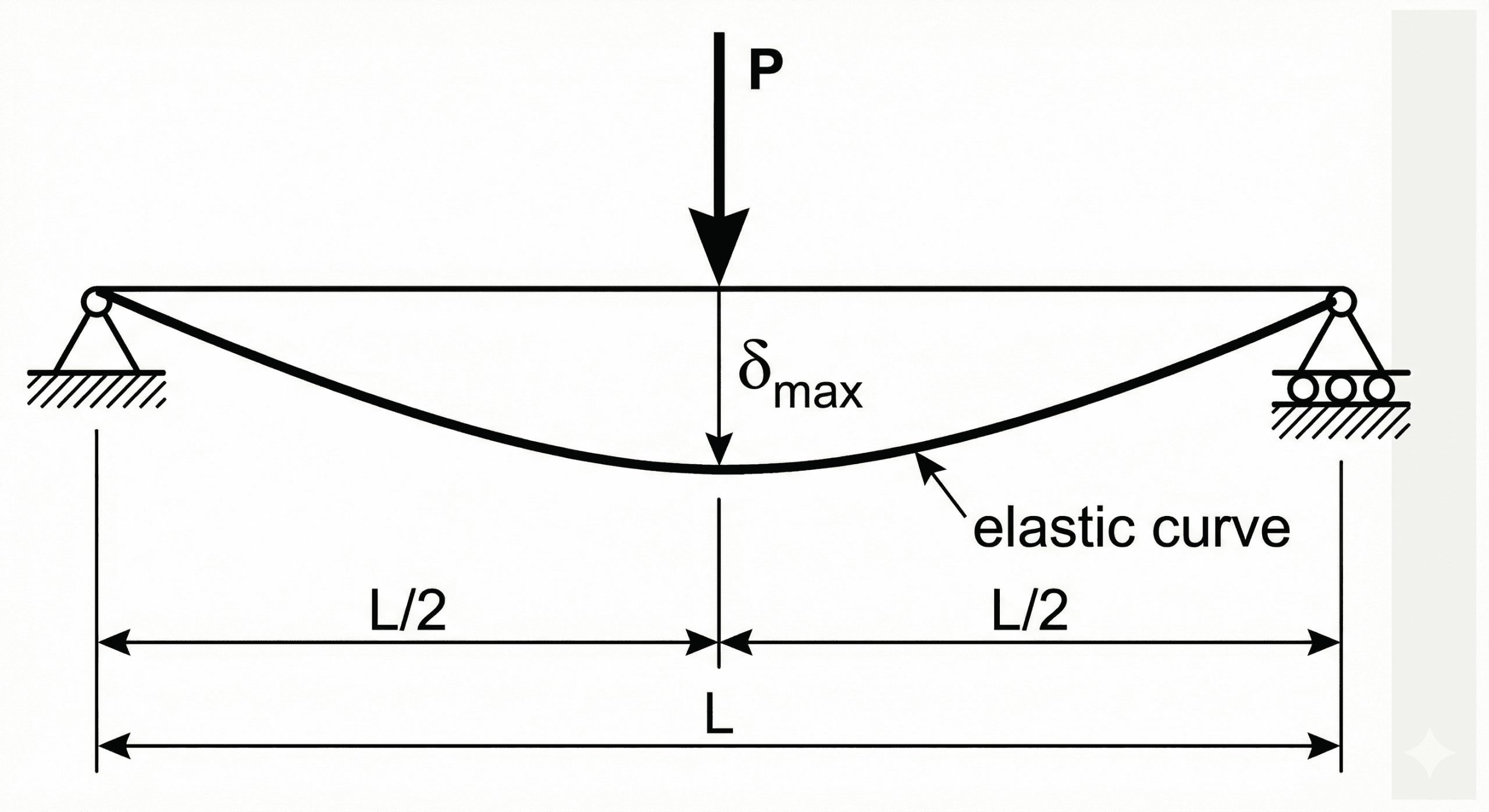

For a simply supported prismatic beam with a single concentrated load \(P\) at midspan, the maximum vertical deflection at midspan is \( \delta_{\max} = P L^3 / (48 E I) \): long spans, flexible materials, small second moments of area, or large loads all increase sag.

The “beam deflection formula” is really a family of closed-form solutions from Euler–Bernoulli beam theory. For each common load case and support condition (simply supported, cantilever, fixed–fixed, uniformly distributed load, point loads, etc.), there is a standard expression that gives the vertical deflection \( \delta(x) \) as a function of position along the beam. The widely quoted \( \delta_{\max} = P L^3 / (48 E I) \) is just one of the most common cases.

In design, deflection is about usability and perception, not just survival. A beam may be strong enough in bending stress, yet still feel “bouncy,” crack finishes, or pond water if deflection is excessive. That’s why serviceability checks using the beam deflection formula sit alongside strength checks, and why many building codes specify deflection ratios like \( \delta_{\max} \leq L/360 \). Once you understand where the formulas come from, you can move beyond tables and use worked examples or a beam calculator to handle less textbook-perfect cases.

Symbols, units & notation in beam deflection formulas

Most beam deflection formulas assume a straight, prismatic beam with constant Young’s modulus \(E\) and second moment of area \(I\). For the simple midspan point-load case, the maximum deflection is \( \delta_{\max} = P L^3 / (48 E I) \). For a uniformly distributed load \(w\) on a simply supported beam, the maximum deflection is \( \delta_{\max} = 5 w L^4 / (384 E I) \). The table below summarizes the common symbols and SI units used across these formulas.

Common notation for beam deflection

| Symbol | Quantity | Typical SI unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( \delta(x) \) | Deflection at position \(x\) | m (or mm) | Vertical displacement of the beam’s neutral axis at location \(x\) along the span, measured from the undeformed (straight) axis. |

| \( \delta_{\max} \) | Maximum deflection | m (or mm) | Largest magnitude of \( \delta(x) \) along the span; often occurs at midspan for symmetric loads on symmetric supports. |

| \( P \) | Point load | N | Concentrated load applied at a specific location, such as a column reaction or equipment weight applied at midspan. |

| \( w \) | Uniformly distributed load | N/m | Load per unit length, such as self-weight, flooring, or snow, assumed constant along some or all of the span. |

| \( L \) | Span length | m | Clear distance between supports (for simply supported beams) or distance from fixed support to free end (cantilevers). |

| \( E \) | Young’s modulus | Pa (N/m²) | Elastic modulus of the material. Steel is roughly \(200\)–\(210~\text{GPa}\), concrete is lower, timber depends on species and grade. |

| \( I \) | Second moment of area | m⁴ | Geometric property of the cross section about the bending axis, sometimes called the “area moment of inertia”. Larger \(I\) means a stiffer section. |

| \( M(x) \) | Bending moment diagram | N·m | Internal bending moment as a function of position. In Euler–Bernoulli theory, curvature is proportional to \(M(x)/(E I)\). |

Unit systems & practical notes

- SI is easiest: use N, m, Pa, and m⁴ consistently. Deflections are typically reported in mm, but calculated in m.

- Imperial / U.S. customary: use kips (k), inches, and \( \text{ksi} \) with care; make sure \(E\), \(I\), and loads are all expressed in a compatible system before using tabulated formulas.

- Signs & directions: most tables give deflection magnitude. In calculations, sagging is often taken as negative; be explicit about your sign convention early and stick to it.

For more complex spans, multiple loads, or different support conditions, you can use closed-form formulas together with a beam calculator (see the related tools section) to explore deflection patterns quickly without doing all the algebra by hand.

How the beam deflection formula comes from Euler–Bernoulli theory

The familiar closed-form deflection expressions come from the Euler–Bernoulli beam equation. Under the usual assumptions (small deflections, linear elastic material, plane sections remaining plane, and a prismatic beam), curvature is proportional to bending moment:

Here \(y(x)\) is the vertical deflection along the beam, and \(M(x)\) is the internal bending moment distribution determined from statics. Integrating twice with respect to \(x\) and applying boundary conditions (zero deflection at supports, zero slope at fixed ends, etc.) yields the deflection curve:

For common loading and support patterns, these integrations have been done once and tabulated, so you rarely need to integrate from scratch. Instead, you select the appropriate case (for example, “simply supported beam, central point load”), plug in \(P\), \(L\), \(E\), and \(I\), and read off the maximum deflection and where it occurs.

Standard closed-form cases engineers use most

While there are many beam deflection formulas, a handful cover a large share of daily engineering work. For a prismatic, simply supported beam:

For a cantilever with a load at the free end:

These formulas already embed the support conditions and load positions through the numerical coefficients (like \(1/48\), \(5/384\), or \(1/3\)). Changing support conditions dramatically changes those coefficients, even with the same span and load.

Deflection vs. bending stress – two sides of the same bending moment

Both deflection and bending stress come from the same bending moment diagram \(M(x)\). Where moment is large, stress is high and curvature is larger. However, stress depends on the extreme fiber distance \(c\) through the familiar flexure formula \( \sigma = M c / I \), while deflection depends on the integrated curvature.

It is entirely possible to have a beam that is safe in bending stress but fails serviceability due to excessive deflection or vibration. That’s why modern design practice always checks both the strength limit state and the serviceability limit state. When a floor feels “bouncy” even though it is structurally safe, it is often a beam deflection problem, not a stress problem.

The Euler–Bernoulli model is remarkably accurate for slender beams and moderate spans, but it begins to break down when shear deformations are significant (short, deep beams), when materials behave nonlinearly (cracked concrete, plastic hinges in steel), or when deflections are large enough to change geometry. In those cases, more advanced models (Timoshenko beams, nonlinear analysis, or full finite-element models) are used, but the basic deflection formulas remain a powerful first check.

Worked beam deflection examples

The examples below mirror common search queries like “beam deflection under point load”, “UDL beam deflection formula example”, and “cantilever beam deflection”. Each one follows the same workflow: choose the correct closed-form expression, plug in consistent units, compute \( \delta_{\max} \), and compare against a deflection limit.

Example 1 – Simply supported steel beam with midspan point load

A simply supported steel beam spans \(L = 6.0~\text{m}\) between supports. A machine exerts a concentrated load of \(P = 30~\text{kN}\) at midspan. The beam is a rolled steel section with \( I = 8.5 \times 10^{-6}~\text{m}^4 \) about the strong axis and Young’s modulus \(E = 210~\text{GPa}\). Estimate the maximum midspan deflection and compare it to an \(L/360\) limit.

- Select the appropriate formula for a simply supported beam with a midspan point load.

- Convert all quantities to consistent SI units.

- Compute \( \delta_{\max} \) and compare against the allowable deflection \(L/360\).

The allowable deflection based on an \(L/360\) limit is:

Result: The predicted midspan deflection of about \(8~\text{mm}\) is less than the \(L/360\) limit of \(16.7~\text{mm}\), so the beam satisfies this serviceability criterion for the given point load.

Example 2 – Simply supported beam with uniformly distributed load

A floor beam spans \(L = 4.5~\text{m}\) and carries a total factored floor load modeled as a uniformly distributed service load of \(w = 10~\text{kN/m}\) (including self-weight). The beam is a composite steel–concrete section with transformed moment of inertia \( I = 1.2 \times 10^{-5}~\text{m}^4 \) and effective modulus \( E = 200~\text{GPa} \). What is the maximum midspan deflection, and does it meet an \(L/480\) limit?

- Use the simply supported, full-span UDL deflection formula.

- Plug in \(w\), \(L\), \(E\), and \(I\) in consistent units.

- Compare \( \delta_{\max} \) with the deflection limit \(L/480\).

The allowable deflection for an \(L/480\) limit is:

Result: The calculated deflection of roughly \(4\)–\(5~\text{mm}\) is below the \(9.4~\text{mm}\) limit, so the beam satisfies this more stringent serviceability requirement as well.

Example 3 – Cantilever balcony beam with end load

A steel cantilever supports a small balcony. The cantilever length from the building face to the free edge is \(L = 2.0~\text{m}\). At the free edge, a factored service load of \(P = 12~\text{kN}\) acts downward (occupancy + self-weight). The cantilever is a rectangular tube with \( I = 3.0 \times 10^{-6}~\text{m}^4 \) and \( E = 210~\text{GPa} \). Estimate the free-end deflection and comment on serviceability if a practical limit of \(L/180\) is used.

- Identify the cantilever end-load deflection formula.

- Substitute \(P\), \(L\), \(E\), and \(I\) with consistent units.

- Compare to the \(L/180\) limit and interpret the result in terms of user comfort.

The \(L/180\) limit gives:

Result: The predicted free-end deflection of about \(5~\text{mm}\) is less than the \(11~\text{mm}\) limit, so from a simple static deflection standpoint, the cantilever seems acceptable. In practice, you would also consider dynamic behavior (vibration), railing detailing, and long-term effects such as creep if the deck or topping is concrete.

Design tips, limits & checks when using beam deflection formulas

Closed-form beam deflection formulas are powerful, but they embed assumptions that are easy to forget. The following patterns and sanity checks help you use them safely in design and exams, and explain why deflection checks sometimes control member selection more than strength.

Standard formulas are based on Euler–Bernoulli theory with:

- Small deflections and small rotations (geometry does not change significantly as the beam bends).

- Linear elastic response with constant \(E\) and uncracked sections (no stiffness reduction for cracking or plasticity).

- Prismatic members with constant \(I\) and no abrupt stiffness changes along the span.

- Idealized supports (perfect pins, rollers, or fixed ends) and idealized load shapes (perfect UDL, point loads, or simple triangles).

As soon as any of these assumptions are badly violated, treat tabulated formulas as rough estimates and consider a more detailed model or finite-element analysis.

- Using the wrong load case (for example, applying the midspan point-load formula to an off-center load or partial UDL).

- Mixing units for \(E\), \(I\), and loads, leading to deflections off by orders of magnitude.

- Forgetting that composite sections (steel + concrete, glulam with concrete topping, etc.) need transformed section properties before using \(I\).

- Checking only maximum deflection at midspan and ignoring slope at supports or intermediate points that affect finishes or connections.

If a result seems surprisingly large or small, revisit the loadcase diagram and verify that the formula you selected matches the support and loading conditions exactly.

To avoid excessive sag and vibration, codes often specify limits like \(L/240\), \(L/360\), or \(L/480\) depending on whether the beam supports plaster, brittle finishes, or sensitive equipment. You can quickly estimate a suitable stiffness by rearranging a deflection formula:

- If required \(I\) is larger than any reasonable section you can choose, consider shortening the span, adding an intermediate support, or using a stiffer material.

- For floor systems, compare your predicted deflection with span/360 or span/480 to anticipate “bounciness” even before detailed code checks.

- Remember that long-term deflection in concrete or timber (creep, shrinkage, moisture effects) can significantly exceed the short-term elastic value.

Once you are comfortable with the algebra behind beam deflection formulas, they become a quick design filter: you can test several cross-section options or span arrangements by hand, then refine promising schemes with more detailed analysis. If deflection is borderline, that’s often a signal to rethink the structural layout rather than simply choosing an oversized section.

Beam deflection formula – FAQ

What is the beam deflection formula in simple terms?

In simple terms, the beam deflection formula tells you how much a beam will sag under a given load. For a common case – a simply supported beam with a point load at midspan – the maximum deflection is \( \delta_{\max} = P L^3 / (48 E I) \). Bigger loads and longer spans increase deflection, while stiffer materials (higher \(E\)) and “chunkier” cross sections (higher \(I\)) reduce it.

How do I know which beam deflection formula to use?

Match the formula to the support conditions and load pattern. Start by sketching: is the beam simply supported, fixed, or cantilevered? Are loads point loads, uniformly distributed loads, or something more complex? Then use a beam table or calculator that clearly labels each case. Using a formula for the wrong case (for example, full-span UDL instead of partial UDL) is one of the most common mistakes in practice and exams.

Is checking beam deflection enough, or do I still need a bending stress check?

You almost always need both. Deflection checks ensure serviceability (no excessive sag, cracking of finishes, or “bouncy” floors), while bending stress checks ensure the material will not yield, crack excessively, or fail. A beam can easily pass a stress check but fail deflection limits, especially for long spans or lightly loaded architectural members where appearance and comfort dominate.

Can I use the beam deflection formula for concrete or timber beams?

Yes, but with care. For concrete and timber, the effective stiffness \(E I\) can change over time due to cracking, creep, and moisture effects. Many design codes provide modifiers or effective stiffness values for serviceability calculations. For quick estimates, you can still use the elastic formulas with an approximate \(E\) and transformed section \(I\), but for final design you should follow the specific code provisions for long-term deflection.

When do I need something more advanced than standard beam deflection formulas?

You need more advanced methods when the structure departs significantly from the simple assumptions: very deep or short beams (shear deformation important), non-prismatic members, large deflections, complex frame interaction, or major cracking/nonlinearity. In those cases, matrix structural analysis or finite-element models are more appropriate, but the beam deflection formulas are still useful for initial sizing checks and plausibility tests.

References & further reading

- Standard mechanics of materials and structural analysis textbooks that derive Euler–Bernoulli beam theory and tabulate deflection formulas for common load and support cases.

- National steel, concrete, and timber design manuals, which include deflection limits, stiffness requirements, and worked design examples for real building and bridge structures.

- University structural engineering course notes available online, often providing additional derivations, example problems, and discussion of serviceability versus strength limit states.