Electrical Engineering · Ohm’s Law

Ohm’s Law – voltage, current, resistance & power explained

Ohm’s Law is the core relationship behind almost every basic circuit: it links voltage, current, resistance, and power so you can size components, troubleshoot faults, and design safe, reliable electronics.

Quick answer: what Ohm’s Law tells you

Core formula

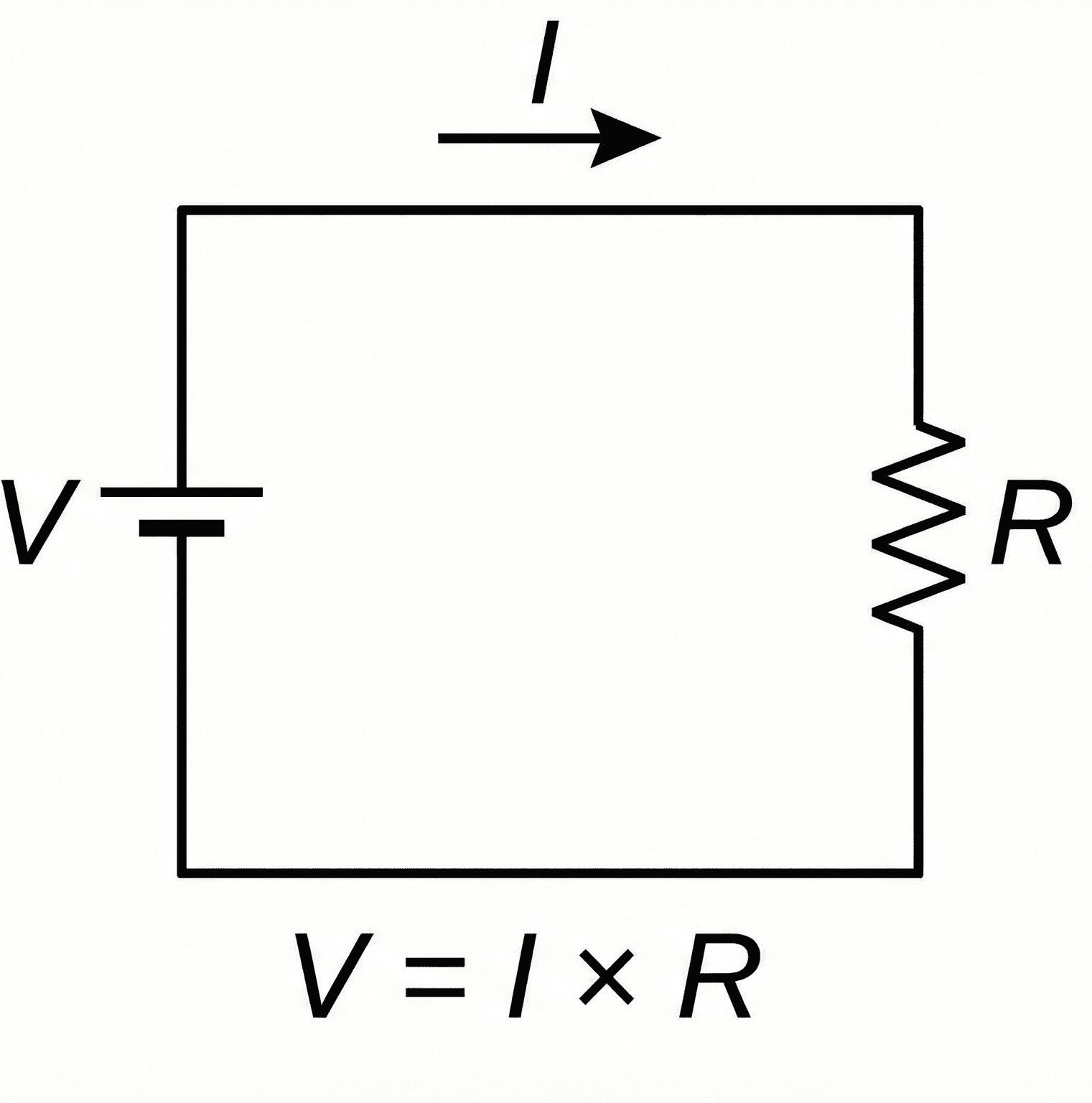

Ohm’s Law says that in an ohmic conductor, the voltage across it is directly proportional to the current through it, with resistance as the constant of proportionality.

At its simplest, Ohm’s Law is a rule of proportionality: double the voltage across a resistor and, if the resistance stays the same, the current doubles. Halve the resistance and, for the same voltage, the current doubles again. This simple relationship is the backbone of everything from phone chargers and LED strips to industrial power systems.

In circuit calculations, Ohm’s Law almost never appears alone. It couples with power relationships like \(P = V \times I\) and network rules for series and parallel resistors. Together, these give you a compact toolkit for answering everyday engineering questions: “Will this resistor overheat?”, “How much current will this load draw?”, or “What supply voltage do I need for this device?”

Variables, symbols & units in Ohm’s Law

In most textbooks and datasheets, Ohm’s Law is written as \(V = I \times R\). Here’s what each symbol means and how it’s typically used in practical electrical and electronics work.

Common notation

| Symbol | Quantity | SI Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| V | Voltage | Volts (V) | Electrical potential difference between two points. Practical units: mV, kV. |

| I | Current | Amperes (A) | The rate of flow of electric charge. Practical units: mA, µA. |

| R | Resistance | Ohms (Ω) | How strongly a component opposes current flow. Practical units: kΩ, MΩ. |

| P | Power | Watts (W) | Rate of energy conversion. Practical units: mW, kW. |

Typical unit systems

- SI (metric): volts (V), amperes (A), ohms (Ω), watts (W). This is the standard in engineering calculations and datasheets.

- Practical electronics: mV / V / kV, µA / mA / A, Ω / kΩ / MΩ, mW / W / kW. Engineers switch prefixes to keep numbers in comfortable ranges (for example, 4.7 kΩ instead of 4700 Ω).

Need to go from formula to numbers? Try the Ohm’s Law Calculator or check back soon for more equations on the Engineering Equations hub.

How the Ohm’s Law equation works

At a microscopic level, conductors are full of charges that move when an electric field is applied. The voltage across a component pushes charge carriers through it; resistance describes how much the material and geometry of that component oppose this motion. For a large class of materials and devices, this opposition is linear over a useful operating range, which means the I–V curve is a straight line passing through the origin. In that linear region, the slope is the conductance and its inverse is the resistance, giving the simple relationship \(V = I \times R\).

Ohm’s Law is an empirical law: it’s based on experimental observation rather than being derived from first principles. But combined with basic circuit rules, it behaves like a design language. Given any two of the four core variables \(V\), \(I\), \(R\), and \(P\), you can quickly solve for the others and understand how changes in one quantity will cascade through a circuit.

Ohm’s Law 12-equation table (“Ohm’s Law wheel”)

The familiar “Ohm’s Law wheel” is just all the ways you can rearrange the core relationships between voltage \(V\), current \(I\), resistance \(R\), and power \(P\). This table collects the 12 forms engineers and students use most often.

| Solved for | Formula | From |

|---|---|---|

| Voltage \(V\) | \( V = I \times R \) | Basic Ohm’s Law |

| Voltage \(V\) | \( V = \dfrac{P}{I} \) | \( P = V \times I \) |

| Voltage \(V\) | \( V = \sqrt{P \times R} \) | \( P = \dfrac{V^{2}}{R} \) |

| Current \(I\) | \( I = \dfrac{V}{R} \) | Basic Ohm’s Law |

| Current \(I\) | \( I = \dfrac{P}{V} \) | \( P = V \times I \) |

| Current \(I\) | \( I = \sqrt{\dfrac{P}{R}} \) | \( P = I^{2} R \) |

| Resistance \(R\) | \( R = \dfrac{V}{I} \) | Basic Ohm’s Law |

| Resistance \(R\) | \( R = \dfrac{V^{2}}{P} \) | \( P = \dfrac{V^{2}}{R} \) |

| Resistance \(R\) | \( R = \dfrac{P}{I^{2}} \) | \( P = I^{2} R \) |

| Power \(P\) | \( P = V \times I \) | Definition of power |

| Power \(P\) | \( P = \dfrac{V^{2}}{R} \) | Combine \( V = I R \) with \( P = V \times I \) |

| Power \(P\) | \( P = I^{2} R \) | Combine \( V = I R \) with \( P = V \times I \) |

Rearranging Ohm’s Law & power equations

In practice, you rarely use only \(V = I \times R\). Engineers constantly rearrange the equations to solve for different unknowns and to include power:

These forms underpin quick mental checks: “If I halve the resistance while keeping voltage fixed, current doubles and the power in that resistor also doubles.” That sort of proportional reasoning is just as important for safe design as punching numbers into a calculator.

Dimensional & sanity checks

Dimensional consistency is a powerful way to catch mistakes. Voltage has units of joules per coulomb, current is coulombs per second, and resistance works out to joule seconds per coulomb squared. When you multiply current and resistance, the units collapse back to volts:

\[ \frac{\text{J}}{\text{C}} = \frac{\text{C}}{\text{s}} \times \frac{\text{J}\cdot\text{s}}{\text{C}^{2}} \]

Similar checks work for power. \(P = V \times I\) yields joules per second, which is exactly one watt. If the units don’t reduce the way you expect, you’ve probably used the wrong prefix or misapplied the equation.

As you move into AC circuits, the same structure still holds but resistance generalizes into complex impedance \(Z\). You work with phasors instead of purely real quantities, and the relationship becomes \(\underline{V} = \underline{I} \times \underline{Z}\). The intuition from DC Ohm’s Law, however, carries straight across: higher impedance means less current for a given applied voltage.

For a deeper theoretical perspective on how voltage, current, and resistance fit into circuit analysis, see standard references like introductory circuit-analysis textbooks or manufacturer guides that walk through Ohm’s Law alongside Kirchhoff’s laws and device models.

Worked Ohm’s Law examples

These examples follow the same steps you’d use in homework, lab work, or design problems. The goal is to turn the abstract equation into a concrete workflow: identify what you know, choose the right form of Ohm’s Law, plug in values, and check power and units.

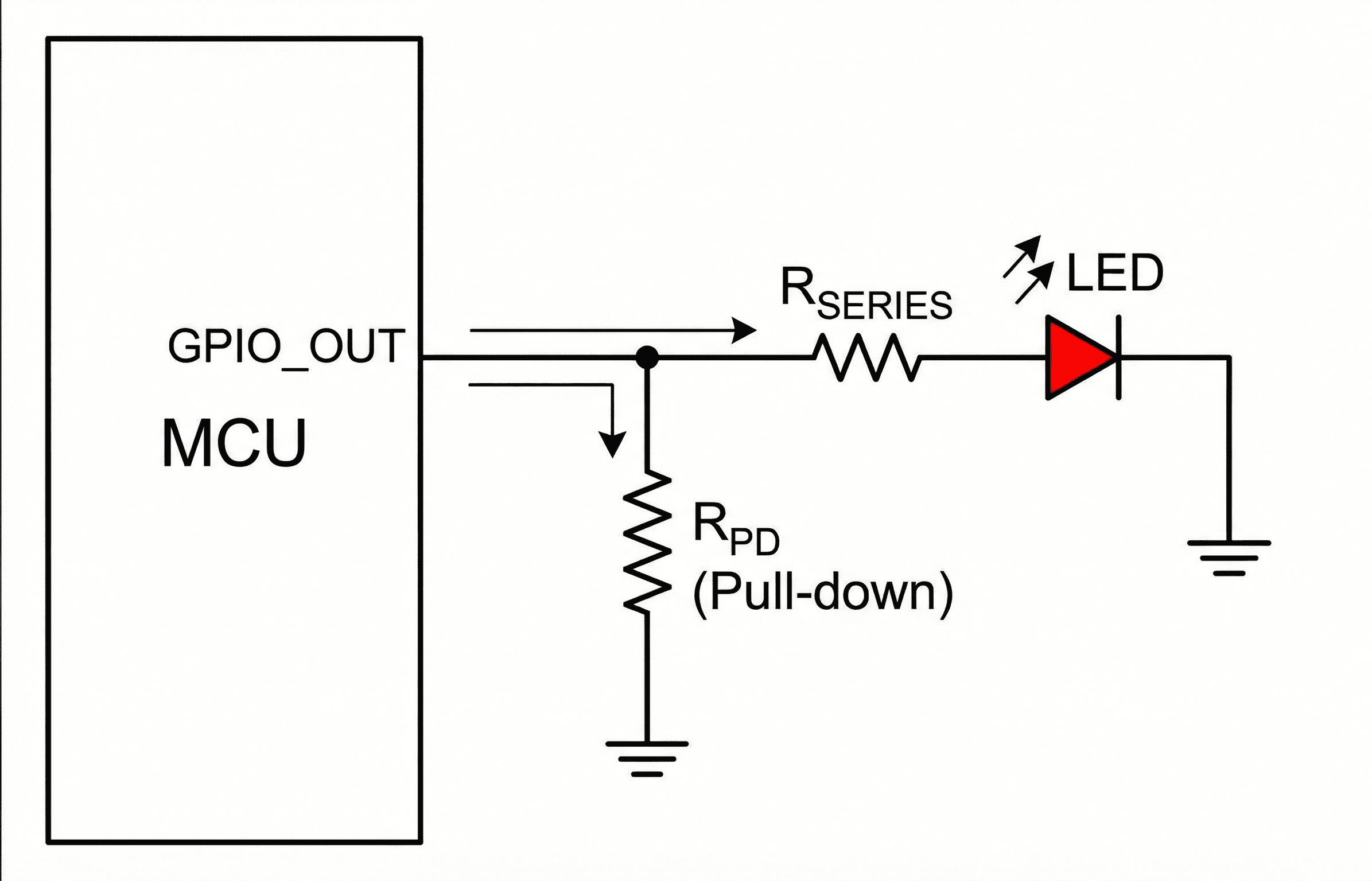

Example 1 – Sizing a resistor for an LED

You have a 12 V DC supply and an LED with a forward voltage of 2.0 V at 20 mA. You want to choose a series resistor so the LED runs near its nominal current. What resistor value and minimum power rating do you need?

Result: The ideal resistance is 500 Ω. The closest standard values are 470 Ω and 510 Ω; both will give currents in the same ballpark. The power calculation shows that a 0.25 W resistor is the bare minimum, so in practice you’d likely choose a 0.5 W part to keep it cool and reliable.

Example 2 – Checking load current & resistor heating

A microcontroller board runs from a regulated 5 V supply. You add a 220 Ω pull-down resistor to ground on a digital output pin. You want to know how much current flows and how much power that resistor dissipates when the pin is driven high at 5 V.

Result: The resistor draws about 23 mA and dissipates roughly 0.11 W when the pin is high. A 0.25 W resistor has more than 2:1 headroom, so it should operate safely. Ohm’s Law plus the power equation give you a quick safety check without needing lab measurements.

Design tips, limitations & common mistakes

Ohm’s Law feels universal at first, but it has clear boundaries. It applies cleanly to ohmic components like ideal resistors over their rated operating range. Once you bring in temperature extremes, semiconductors, or reactive components, you need to think more carefully about when and how to use it.

Classical Ohm’s Law assumes:

- The device behaves linearly over the operating range, so the I–V relationship is a straight line.

- Temperature, magnetic field, and other environmental factors do not significantly change resistance.

- You’re focusing on the resistive behavior of the component, not energy stored in inductors or capacitors.

- Forgetting power: Designers sometimes compute current correctly but ignore \(P = V \times I\), leading to resistors that run far too hot.

- Putting the wrong resistance in the equation: In multi-resistor networks it’s easy to use a single resistor instead of the equivalent series or parallel value.

- Applying Ohm’s Law where it doesn’t fit: Devices like diodes, LEDs, and transistors have strongly non-linear I–V curves. You can sometimes approximate behavior locally, but you can’t treat them as fixed resistances.

Before trusting a result, do a quick sense check:

- If voltage doubles and resistance stays constant, current should also double. If your math doesn’t reflect that, something is off.

- If resistance increases by a factor of ten, current should drop by roughly the same factor for a fixed voltage.

- Estimated power should line up with intuition: tiny SMD resistors should not be dissipating watts of power on paper unless you’ve explicitly chosen high-power parts.

As you go beyond simple DC circuits, it’s helpful to think of Ohm’s Law as the linear core inside a more complex system. In AC analysis, impedances play the role of resistance; in semiconductor circuits, small-signal models give you a local “dynamic resistance” around a bias point. In all cases, the intuition you build on simple resistor networks carries forward.

Ohm’s Law – frequently asked questions

What is Ohm’s Law in simple terms?

Ohm’s Law says that the voltage across a resistor equals the current through it multiplied by its resistance. If you increase voltage, current goes up in direct proportion as long as the resistance stays constant.

How do I use Ohm’s Law in practice?

Start by identifying which two quantities you already know. Rearrange the formulas to solve for the unknown, plug in values with consistent units, and then check power and sanity. For fast calculations you can also use an Ohm’s Law Calculator that solves for voltage, current, resistance, and power.

Does Ohm’s Law work for all materials and AC circuits?

No. Ohm’s Law works cleanly for ohmic devices where the I–V curve is linear. Components like diodes and transistors are non-ohmic, and in AC circuits inductors and capacitors introduce reactance. In those cases you use generalized forms such as impedance and device models, but the core ideas behind Ohm’s Law still guide how you think about the circuit.

References & further reading

- SparkFun Electronics, Voltage, Current, Resistance, and Ohm’s Law. View tutorial

- Fluke, What is Ohm’s Law?. View application note