Thermodynamics · Ideal Gas Law

Ideal Gas Law – pressure, volume, temperature & moles explained

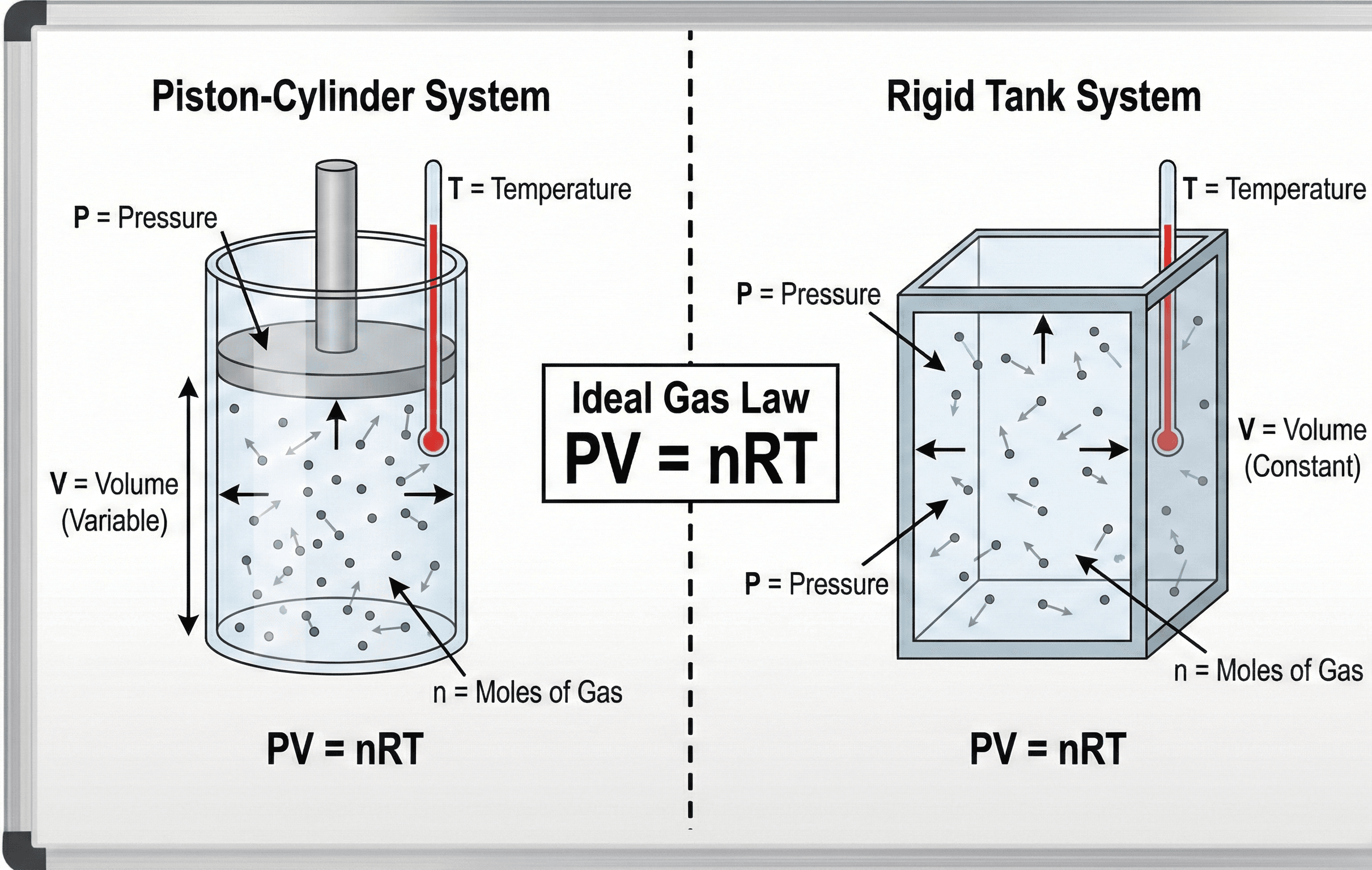

The Ideal Gas Law links pressure, volume, temperature, and moles in a single equation, giving you a practical way to estimate gas behavior for cylinders, piping, and introductory thermodynamics problems.

Quick answer: what the Ideal Gas Law tells you

Core formula

The Ideal Gas Law says that for a simple gas, the product of pressure and volume equals the number of moles times the gas constant times absolute temperature, so changing any one of these four quantities forces at least one of the others to adjust.

At the engineering-intro level, the Ideal Gas Law is your main shortcut for gas behavior. It combines several simpler gas laws into one relationship: pressure \(P\), volume \(V\), temperature \(T\), and moles \(n\). If you know any three, you can solve for the fourth. Most “how do I calculate final pressure?” or “what tank volume do I need?” questions boil down to rearranging \( P V = n R T \) with the right units and assumptions.

The law is “ideal” because it assumes gas molecules are point particles that don’t attract or repel each other and occupy negligible volume. Real gases deviate from this behavior, especially at high pressures and low temperatures, but \( P V = n R T \) is surprisingly accurate for many common engineering situations. As you’ll see in the worked examples, it’s usually the unit conversions and reference conditions that cause more trouble than the equation itself.

Symbols, units & notation in the Ideal Gas Law

In its most common form, the Ideal Gas Law is written as \( P V = n R T \). In some process calculations you’ll see variants like \( P v = R T \), where \(v\) is specific volume (volume per unit mass) instead of total volume. Regardless of notation, the same four state variables appear, and the key to getting correct answers is keeping the symbols and units straight.

Core symbols & SI units

| Symbol | Quantity | Typical SI unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( P \) | Pressure | pascal (Pa) or bar | Absolute pressure of the gas. \( 1~\text{bar} = 10^5~\text{Pa} \). Always use absolute pressure (gauge + atmospheric) in \( P V = n R T \). |

| \( V \) | Volume | m³ | Total volume occupied by the gas, usually the internal volume of a tank, cylinder, or pipe section under consideration. |

| \( n \) | Amount of substance | mol | Moles of gas. Related to mass by \( n = \dfrac{m}{M} \), where \(m\) is mass and \(M\) is molar mass (kg/mol). |

| \( T \) | Temperature | kelvin (K) | Absolute temperature of the gas. Convert from °C by \( T[\text{K}] = T[^\circ\text{C}] + 273.15 \). Never plug Celsius directly into \( P V = n R T \). |

| \( R \) | Gas constant | varies with units | Universal gas constant or gas-specific constant. Common values include \( R = 8.314~\text{J/(mol·K)} \) or \( R = 0.082057~\text{L·atm/(mol·K)} \); choose the version that matches your pressure and volume units. |

Common choices for \(R\) and unit combinations

| Pressure | Volume | R value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pa | m³ | \( 8.314~\text{J/(mol·K)} \) | Fully SI-consistent form; power and energy calculations match directly with joules. |

| atm | L | \( 0.082057~\text{L·atm/(mol·K)} \) | Very common in chemistry problems and lab-scale gas calculations. |

| kPa | m³ | \( 8.314~\text{kPa·L/(mol·K)} \approx 0.008314~\text{kPa·m³/(mol·K)} \) | Often used in engineering hand calculations when pressures are given in kPa or bar. |

Unit systems & practical notes

- Always convert pressure to an absolute basis before using \( P V = n R T \). Add atmospheric pressure to gauge readings where needed.

- Temperature must be in kelvins. Converting from °C is a one-line step, but forgetting it is one of the most common mistakes with the Ideal Gas Law.

- Pick an \(R\) value that matches your pressure and volume units; if you change units, update \(R\) or convert the variables accordingly.

For quick numeric checks and unit juggling, you can use a dedicated Ideal Gas Law calculator to experiment with different pressures, volumes, temperatures, and gas amounts.

How the Ideal Gas Law models gas behavior

Conceptually, the Ideal Gas Law comes from kinetic theory: gas molecules move randomly, collide elastically with each other and the container walls, and the macroscopic quantities \(P\), \(V\), and \(T\) reflect averages over huge numbers of particles. Pressure is related to how often and how hard molecules hit the walls, temperature tracks their average kinetic energy, and volume sets how much space they have to move in.

At a practical level, you rarely need the derivation in day-to-day engineering work; instead, you exploit the simple structure of \( P V = n R T \). Holding any two of \(P\), \(V\), and \(T\) fixed defines a direct proportionality between the other pair. For example, with fixed \(n\) and \(V\), pressure is proportional to temperature; with fixed \(n\) and \(T\), pressure is inversely proportional to volume.

Rearranging \( P V = n R T \) for different unknowns

Most calculation steps boil down to rearranging the Ideal Gas Law algebraically and then managing units. The following scalar forms assume a single, uniform gas state:

If you prefer mass rather than moles, introduce the molar mass \(M\) and specific gas constant \(R_s\):

Here \(v\) is specific volume (m³/kg). The form \( P v = R_s T \) is common in thermodynamics tables and cycle diagrams, especially for air-standard analyses.

Connecting to combined gas laws & state changes

Many textbook identities like Boyle’s Law, Charles’s Law, and the combined gas law are just special cases of \( P V = n R T \). For a fixed amount of gas \(n\):

This combined form is handy for “before and after” problems. You may not explicitly compute \(n\); instead, you relate initial and final states for the same gas using ratios. This is especially useful for estimating how tank pressure changes with temperature swings or how volume changes when gas is transferred between vessels.

Checking ideal-gas assumptions

The Ideal Gas Law is most accurate when:

- Pressures are not extremely high (roughly up to a few tens of bar for many gases).

- Temperatures are well above the gas’s saturation or critical temperature.

- The gas is relatively light (for example, air, nitrogen, oxygen, hydrogen, methane in many conditions).

When deviations matter, a compressibility factor \(Z\) is introduced:

For ideal gases, \(Z \approx 1\). Real-gas charts and equations of state provide \(Z\) values for high-pressure natural gas, refrigerants, and other industrial fluids when you’ve moved beyond the “good enough” regime for \( P V = n R T \) alone.

Worked examples using the Ideal Gas Law

These examples mirror typical questions engineers and students search for when using the Ideal Gas Law. Each one shows how to set up the equation, manage units, and interpret the result rather than just plugging numbers into a formula.

Example 1 – How many moles of air are in a storage tank?

A rigid air tank has an internal volume of \(0.500~\text{m}^3\). The absolute pressure inside is \(600~\text{kPa}\) and the temperature is \(25^\circ\text{C}\). Assuming air behaves as an ideal gas, how many moles of air are in the tank?

- Convert the given temperature to kelvins.

- Choose an \(R\) value consistent with pressure and volume units.

- Rearrange the Ideal Gas Law to solve for moles \(n\).

Result: The tank contains roughly \(1.2 \times 10^2\) moles of air under the stated conditions. If you know the molar mass of air (\(\approx 28.97~\text{g/mol}\)), you can convert this to mass for further calculations.

Example 2 – Final pressure after heating at constant volume

A sealed, rigid cylinder initially holds nitrogen at \(P_1 = 200~\text{kPa}\) and \(T_1 = 20^\circ\text{C}\). The cylinder is heated to \(T_2 = 120^\circ\text{C}\) while the volume and amount of gas remain constant. What is the final pressure \(P_2\)?

- Convert both temperatures to kelvins.

- Use the combined form \( \dfrac{P_1}{T_1} = \dfrac{P_2}{T_2} \) for constant \(n\) and \(V\).

- Solve for \(P_2\) and interpret the increase.

Result: Heating the gas from \(20^\circ\text{C}\) to \(120^\circ\text{C}\) at constant volume raises the pressure from \(200~\text{kPa}\) to about \(270~\text{kPa}\). This kind of estimate is crucial when checking that tanks and fittings remain within their pressure ratings during temperature swings.

Example 3 – Required tank volume for compressed air storage

You need to store \(5.0~\text{kg}\) of air in a receiver at a maximum operating pressure of \(900~\text{kPa}\) absolute and a design temperature of \(40^\circ\text{C}\). Estimate the minimum internal volume of the tank assuming ideal-gas behavior and take the molar mass of air as \(M = 28.97~\text{kg/kmol}\).

- Convert the air mass to moles, then to amount of substance \(n\).

- Convert the temperature to kelvins and choose compatible units for \(P\), \(V\), and \(R\).

- Rearrange \( P V = n R T \) to solve for volume \(V\).

Result: A receiver volume of about \(0.50~\text{m}^3\) (500 liters) is the theoretical minimum to hold \(5~\text{kg}\) of air under the stated ideal-gas conditions. In practice, you would increase this volume to account for non-ideal behavior, pressure drops, and safety factors.

Design tips, limits & checks when using \( P V = n R T \)

The Ideal Gas Law can be both powerful and misleading. Used correctly, it gives quick, reasonably accurate estimates for many air and gas-handling problems. Used carelessly, it can hide unit mistakes and physical limitations. These notes highlight the main engineering pitfalls and sanity checks.

Most numerical issues with the Ideal Gas Law come from unit mismatches rather than physics. Before trusting your answer, run through a short checklist:

- Is pressure absolute (kPa, bar, Pa) rather than gauge? If you started with gauge, did you add local atmospheric pressure?

- Is temperature in kelvins, not °C or °F? Did you convert correctly from the given scale?

- Does your chosen \(R\) match the pressure and volume units you ended up using?

- For air and many light gases below roughly 10–20 bar and moderate temperatures, \( P V = n R T \) is often accurate within a few percent.

- Near saturation or at very high pressures (for example, dense CO₂ or natural gas pipelines), real-gas effects and compressibility factors become important.

- Refrigerants, steam near saturation, and cryogenic fluids generally require property tables or more advanced equations of state.

When in doubt, compare a quick ideal-gas estimate against data from property charts or software to see whether deviations are acceptable for your design decisions.

Even without detailed property data, you can often spot unrealistic results just from magnitudes and trends:

- If a small temperature change predicts a huge pressure swing at modest conditions, recheck whether you accidentally used °C instead of K.

- If storing a modest mass of gas requires an enormous volume at a given pressure, verify both the molar mass and the pressure basis.

- For compressed air receivers and gas cylinders, compare your estimates to standard cylinder sizes or vendor datasheets to see if they are in the right ballpark.

In higher-level thermodynamics and process design, the Ideal Gas Law often appears as the first step of a more detailed model rather than the final answer. It still provides a fast way to set initial conditions, check software output, or estimate the impact of operating changes before you commit to more complex simulations.

Ideal Gas Law – FAQ

What is the Ideal Gas Law in simple terms?

In everyday language, the Ideal Gas Law says that a gas’s pressure, volume, temperature, and amount are all tied together. If you heat a fixed amount of gas in a rigid tank, the pressure goes up. If you let it expand while holding pressure constant, the volume increases. Mathematically that relationship is \( P V = n R T \), where \(P\) is absolute pressure, \(V\) is volume, \(n\) is moles of gas, \(T\) is absolute temperature in kelvins, and \(R\) is the gas constant.

Can I use Celsius in the Ideal Gas Law?

No – the temperature in \( P V = n R T \) must always be in kelvins. If you are given a temperature in °C, convert it using \( T[\text{K}] = T[^\circ\text{C}] + 273.15 \). Using °C directly leads to wrong ratios, especially in combined-gas-law problems where the temperature terms appear in numerator and denominator.

Should I use gauge pressure or absolute pressure with the Ideal Gas Law?

Always work with absolute pressure in the Ideal Gas Law. If your gauge reads \(P_\text{gauge}\), convert to absolute pressure via \( P_\text{abs} = P_\text{gauge} + P_\text{atm} \), where \(P_\text{atm}\) is local atmospheric pressure (about \(101.3~\text{kPa}\) at sea level). Working directly with gauge values without this correction is a common source of large errors.

When is the Ideal Gas Law not accurate enough?

The Ideal Gas Law becomes less accurate at high pressures, low temperatures near condensation, or for strongly interacting molecules (for example, CO₂ at supercritical conditions or many refrigerants). In those cases, engineers use real-gas models such as the van der Waals equation, Peng–Robinson, or tabulated property data with a compressibility factor \(Z\). A quick check is to compare your operating state to published \(Z\)-factor charts: if \(Z\) deviates far from 1, you should not rely on \( P V = n R T \) alone.

References & further reading

- Standard university thermodynamics and physical chemistry textbooks covering the Ideal Gas Law, combined gas laws, and kinetic theory.

- Thermophysical property databases and charts (for example, NIST WebBook and vendor application notes) that compare ideal-gas estimates with real-gas data for common industrial gases.

- Introductory engineering course notes and problem sets on gas storage, piping, and air systems, which show how \( P V = n R T \) connects with energy balances and practical design constraints.