Mechanical & Structural Engineering · Shear Stress Equation

Shear Stress Equation – internal force, area & failure limits explained

The shear stress equation relates internal shear force to the resisting area, helping you check bolts, beams, welds and fluids for safe performance before they reach their failure limits.

Quick answer: what the shear stress equation tells you

Core formula (average shear stress)

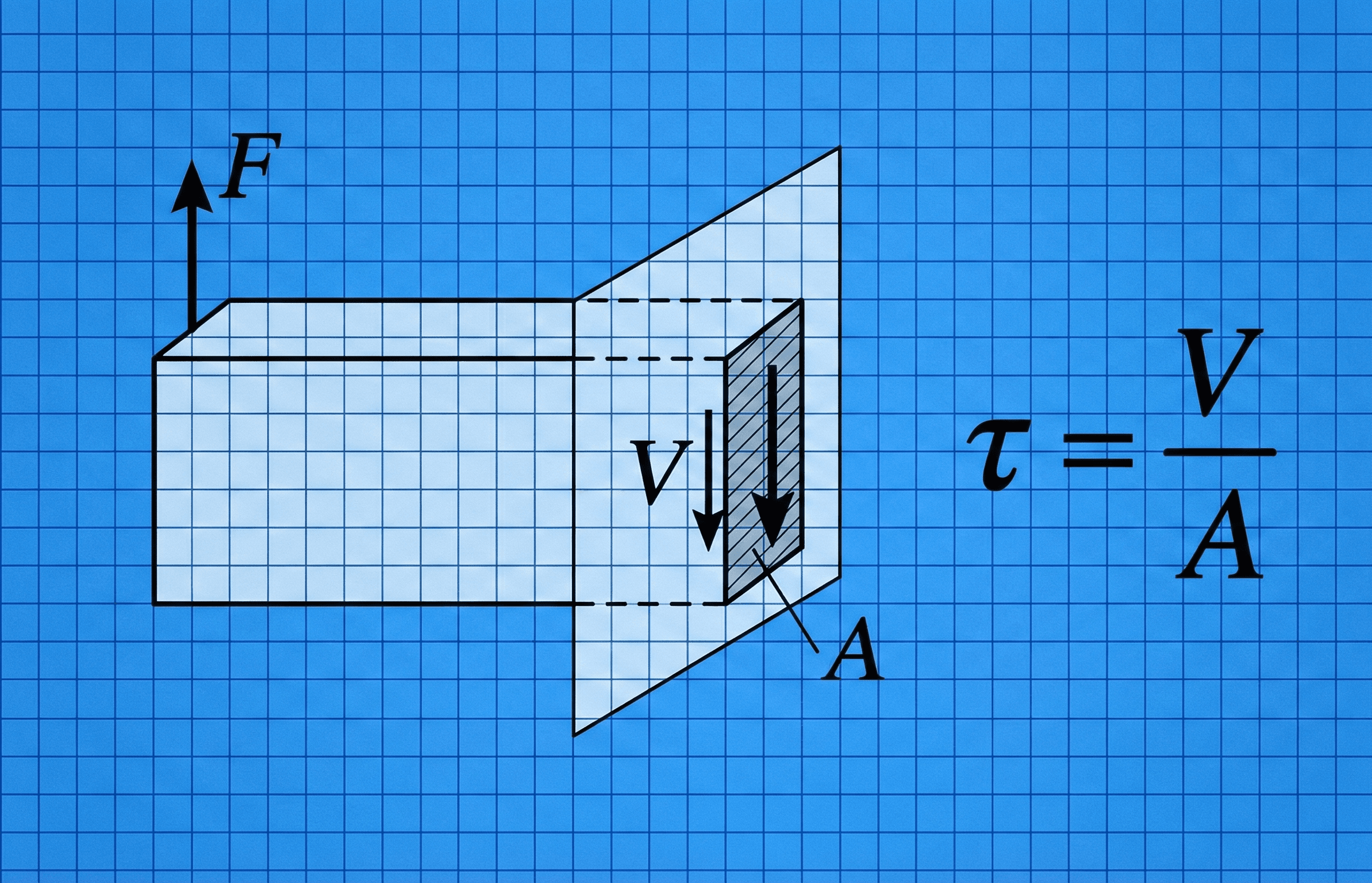

The shear stress equation says the average shear stress \( \tau \) on a plane equals the internal shear force \( V \) (or \(F\)) acting parallel to that plane divided by the area \(A\) resisting the shear.

In most strength-of-materials and machine design problems, shear stress is the internal “sliding” stress that acts parallel to a cut plane and tries to make one part of a material slide past the adjacent part. The basic design question is always the same: “Given this shear force, is the material’s shear capacity enough?” The average shear stress equation \( \tau = V / A \) gives your first-pass answer, which you then compare to an allowable or ultimate shear strength from material data.

For many practical components, the shear stress is not perfectly uniform across the area – beams have higher shear near the neutral axis, and fluids have zero shear at the centerline and maximum at the wall. But the average equation is still the starting point. You can see more detailed distributions and realistic scenarios in the worked examples and sanity-check your designs using the design tips & limits section.

Symbols, units & notation for the shear stress equation

In solid mechanics, the shear stress equation is usually written as \( \tau = \dfrac{V}{A} \) or \( \tau = \dfrac{F}{A} \), where \(V\) (or \(F\)) is the internal shear force acting along a plane and \(A\) is the area of that plane. In fluids, a closely related form is \( \tau = \mu \dfrac{\mathrm{d}u}{\mathrm{d}y} \), tying shear stress to velocity gradients. The table below summarizes the most common symbols and units.

Common shear stress notation

| Symbol | Quantity | Typical SI unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( \tau \) | Shear stress | Pascal (Pa) = N/m² | Internal stress acting parallel to a plane, representing how strongly adjacent material layers are trying to slide past each other. |

| \( V \) | Internal shear force | Newton (N) | Resultant shear force on a cut section from external loads; often taken from a shear force diagram in beam problems. |

| \( F \) | Shear force (alternate) | Newton (N) | Sometimes used instead of \(V\) when analyzing simple lap joints, pins or fasteners where there is no separate bending/shear diagram. |

| \( A \) | Area resisting shear | m² | Cross-sectional area over which the shear force is distributed (for example, bolt shear area, weld throat area, beam web area). |

| \( \mu \) | Dynamic viscosity | Pa·s | Proportionality constant in Newtonian fluids linking shear stress and velocity gradient via \( \tau = \mu \dfrac{\mathrm{d}u}{\mathrm{d}y} \). |

| \( \dfrac{\mathrm{d}u}{\mathrm{d}y} \) | Velocity gradient | s⁻¹ | Rate of change of fluid velocity \(u\) with distance \(y\) normal to the wall; higher gradients produce higher wall shear. |

Unit systems & quick checks

- SI design standard: express shear stress in MPa (megapascals) for solid mechanics, where \(1~\text{MPa} = 10^6~\text{N/m}^2\).

- U.S. customary units: shear stress is often reported in ksi (kips per square inch). Keep forces in kips and areas in in² to avoid hidden conversion factors.

- Dimensional sanity check: any shear stress result should reduce to force/area. If you end up with N·m or N·s/m³, something in your algebra or units is off.

Once the symbols and units are clear, the workflow is straightforward: find the shear force on the section, compute the resisting area, apply \( \tau = V/A \), and compare to an allowable shear stress from codes or material data.

How the shear stress equation connects loads to material behavior

At a physical level, shear stress measures how intensely one layer of material wants to slide past a neighboring layer. When you apply a transverse load to a beam, force to a lap joint, or velocity gradient to a fluid, the material internally develops shear to resist that sliding. The equation \( \tau = V/A \) is the simplest form of that relationship: total shear force shared uniformly across area.

Average shear stress in solid mechanics

For many discrete components like bolts, pins, rivets and short welds, engineers assume the shear stress is approximately uniform over the resisting area. That leads directly to the average shear equation:

Here \(V\) is the total shear force carried by the section and \(A\) is the effective shear area. In a double-shear pin, for example, the pin is sheared along two parallel planes, so the total resisting area is \(A = 2 A_{\text{single-plane}}\). Likewise, if a plate is connected by multiple bolts sharing the load, you divide the total shear force by the number of bolts to get the force per bolt before applying \( \tau = F_{\text{bolt}}/A_{\text{bolt}} \).

This average model is conservative when stress is roughly uniform, but it can be unconservative if actual stress is highly peaked (for example, near re-entrant corners or fillets). That’s why codes often cap allowable average shear stress well below the material’s ultimate shear strength.

Shear stress in beams & non-uniform distributions

In beams under transverse loading, the shear stress is not uniform over the cross-section. The full derivation from shear flow gives the more detailed expression

where \(Q\) is the first moment of area above (or below) the point of interest, \(I\) is the second moment of area about the neutral axis, and \(b\) is the local width of the section. This formula predicts maximum shear at the neutral axis and zero at the outer fibers in rectangular sections.

However, for quick estimates and for components like web panels or thin plates, many designers still use the simpler average equation \( \tau \approx V/A_{\text{web}} \) as a first-pass check, then refine with \(VQ/Ib\) if they are near capacity.

Shear stress in Newtonian fluids

In fluid mechanics, shear stress arises from layers of fluid moving past each other at different speeds. Newtonian fluids obey the linear relationship

where \(u\) is the fluid velocity parallel to the wall and \(y\) is the coordinate normal to the wall. A steeper velocity gradient (for example, in a narrow gap or high-speed flow) produces higher shear stress for the same viscosity \( \mu \). This concept is central when sizing lubrication films, calculating drag on plates, or estimating pressure drops in laminar pipe flow.

Across all of these cases, the key idea is the same: higher shear force or steeper velocity gradients acting over a smaller area produce higher shear stress. The shear stress equation simply makes that intuition quantitative so you can design against yielding, fatigue, wear or excessive deformation.

Worked examples using the shear stress equation

The examples below cover common search scenarios: checking bolts in shear, estimating shear stress in a beam web, and computing wall shear in a viscous fluid. The same workflow applies broadly: identify the shear force on the section, compute the area or gradient, apply the appropriate form of the equation, and compare the result to allowable limits.

Example 1 – Shear stress on a bolt in single shear

Two steel plates are connected by a single bolt in single shear carrying a service load of \(25~\text{kN}\). The bolt shank diameter is \(d = 12~\text{mm}\). Assuming the load is shared entirely by the bolt in shear, what is the average shear stress in the bolt shank, and is it acceptable if the allowable shear stress is \(100~\text{MPa}\)?

- Compute the shear area (cross-sectional area of the bolt in single shear).

- Apply \( \tau_{\text{avg}} = V / A \) with \(V = 25~\text{kN}\).

- Compare the result to the allowable shear stress.

Result: The average shear stress in the bolt is about \(221~\text{MPa}\), which is more than double the allowable \(100~\text{MPa}\). This bolt size would be unsafe for the given load; you would need a larger diameter bolt, multiple bolts sharing the load, or a lower design load.

Example 2 – Average shear stress in a rectangular beam web

A simply supported rectangular steel beam carries a maximum shear force of \(V = 60~\text{kN}\) at midspan. The beam cross-section is \(200~\text{mm}\) deep and \(80~\text{mm}\) wide. Estimate the average shear stress in the cross-section, treating it as a solid rectangle. Comment on whether this value is reasonable for mild structural steel.

- Compute the cross-sectional area.

- Apply the average shear equation \( \tau_{\text{avg}} = V / A \).

- Compare to typical allowable shear stresses for mild steel.

Result: The average shear stress is only about \(3.75~\text{MPa}\), which is extremely modest compared to typical mild steel yield strengths (on the order of \(250~\text{MPa}\)). Even after applying code-based reduction factors and safety factors, this level of shear stress is comfortably within limits, which is consistent with the fact that beams usually fail in bending rather than shear unless web areas are very thin or heavily perforated.

Example 3 – Wall shear stress in laminar fluid flow

Consider a Newtonian oil with dynamic viscosity \( \mu = 0.25~\text{Pa·s} \) flowing steadily between two large parallel plates separated by \(5~\text{mm}\). The bottom plate is stationary and the top plate moves at \(0.6~\text{m/s}\), producing a linear velocity profile. What is the shear stress at each plate?

- Use the linear velocity profile to find the velocity gradient \( \dfrac{\mathrm{d}u}{\mathrm{d}y} \).

- Apply \( \tau = \mu \dfrac{\mathrm{d}u}{\mathrm{d}y} \) for a Newtonian fluid.

- Interpret the direction and magnitude of the shear at each plate.

Result: The wall shear stress magnitude is \(30~\text{Pa}\) at each plate, acting opposite the direction of the nearby fluid motion. This value is typical for moderate-speed, viscous laminar flows in narrow gaps, and it can be used to estimate the required driving force or power loss in lubrication and bearing design.

Design tips, limits & checks when using the shear stress equation

The shear stress equation is simple, but real components and fluids introduce details that can make or break a design. Use the following points as a mental checklist whenever you apply \( \tau = V/A \) or \( \tau = \mu \dfrac{\mathrm{d}u}{\mathrm{d}y} \).

- Use \( \tau = V/A \) for average shear in discrete components like bolts, pins, weld throats and short lap joints.

- Use more advanced forms like \( \tau = VQ/(I b) \) for detailed shear distributions in beams and flanged sections.

- Use \( \tau = \mu \dfrac{\mathrm{d}u}{\mathrm{d}y} \) only for Newtonian fluids with reasonably known velocity profiles; non-Newtonian fluids need different constitutive relations.

- Forgetting double shear: if a pin or bolt is sheared in two planes, the total area is doubled, which halves the average shear stress.

- Using the wrong area: for welds, use effective throat area rather than the full leg length; for bolts, use root or stress area if specified by the design code.

- Mixing units: combining kN with mm² without converting to consistent units can misstate stress levels by orders of magnitude.

Before finalizing a design, cross-check your shear stress calculations against material limits and service conditions:

- Compare computed \( \tau \) with allowable design shear stress from standards or manufacturer data, including safety factors.

- Consider fatigue: fluctuating shear stresses in shafts, welds and fasteners can cause failure well below static shear capacity.

- Check compatibility: ensure shear deformations do not cause misalignment or serviceability issues even if stresses are below ultimate strength.

If an initial \( \tau = V/A \) check suggests you are close to allowable limits, that is usually a signal to refine your model: consider more accurate stress distributions, secondary load paths, dynamic effects, or even finite-element analysis. For many everyday connections, though, a carefully executed average shear stress calculation combined with conservative design values provides a robust and efficient solution.

Shear stress equation – FAQ

What is the shear stress equation in simple terms?

In simple terms, the shear stress equation says that shear stress equals shear force divided by the area carrying that force: \( \tau = V/A \). If you push harder (higher \(V\)) or make the area smaller, the stress goes up; if you spread the same force over a larger area, the stress goes down. It’s the shear counterpart of the more general idea “stress = load / area.”

How do I calculate shear stress on a bolt or pin?

To calculate shear stress on a bolt or pin: (1) determine the total shear force carried by that fastener (divide total joint shear by the number of bolts if they share load equally); (2) identify how many shear planes are active (single or double shear); (3) compute the resisting area \(A\) for one plane and multiply by the number of planes; and (4) apply \( \tau_{\text{avg}} = V / A \). Compare the result to the allowable shear stress for the bolt material, including any safety factors from the relevant design code.

What units should I use for shear stress?

In SI, shear stress is expressed in Pascals (Pa), usually reported in MPa for engineering work. Since \(1~\text{Pa} = 1~\text{N/m}^2\), make sure your force is in newtons and area is in square meters (or newtons and square millimeters with the conversion \(1~\text{N/mm}^2 = 1~\text{MPa}\)). In U.S. customary units, shear stress is often given in psi or ksi, with force in pounds (lb) or kips and area in square inches.

What is the difference between normal stress and shear stress?

Normal stress acts perpendicular to a surface and is associated with tension or compression (pulling or pushing straight through an area), commonly computed with \( \sigma = P/A \). Shear stress acts parallel to a surface and is associated with sliding between adjacent layers, computed with \( \tau = V/A \) or related formulas. Real components often experience both normal and shear stresses simultaneously, which is why combined-stress criteria like von Mises are used in detailed design.

Is the shear stress from \( \tau = V/A \) always accurate?

No. \( \tau = V/A \) gives an average shear stress over the area. It is very useful for sizing bolts, pins and some simple connections, but real stress distributions are often non-uniform and may peak near edges, fillets or discontinuities. When designs run close to material limits, codes usually require more refined methods (like \(VQ/Ib\) for beams, torsion theory for shafts or finite-element analysis) and conservative safety factors.

References & further reading

- Standard strength of materials and mechanics of materials textbooks, which derive shear stress equations for beams, shafts, welds and fasteners and provide design examples.

- Fluid mechanics texts covering Newtonian viscosity, velocity gradients and wall shear, especially in laminar flows between plates and in circular pipes.

- Structural and machine design codes (for example, steel or concrete design standards, bolting and welding specifications), which give allowable shear stresses and detailed rules for real-world components.