Mechanical Engineering · Hooke’s Law

Hooke’s Law – spring force, stiffness & deflection explained

Hooke’s Law relates the force in a spring to how far it is stretched or compressed, giving engineers a simple, powerful way to size springs, predict deflection, and estimate stored elastic energy in linear systems.

Quick answer: what Hooke’s Law tells you about springs

Core formula

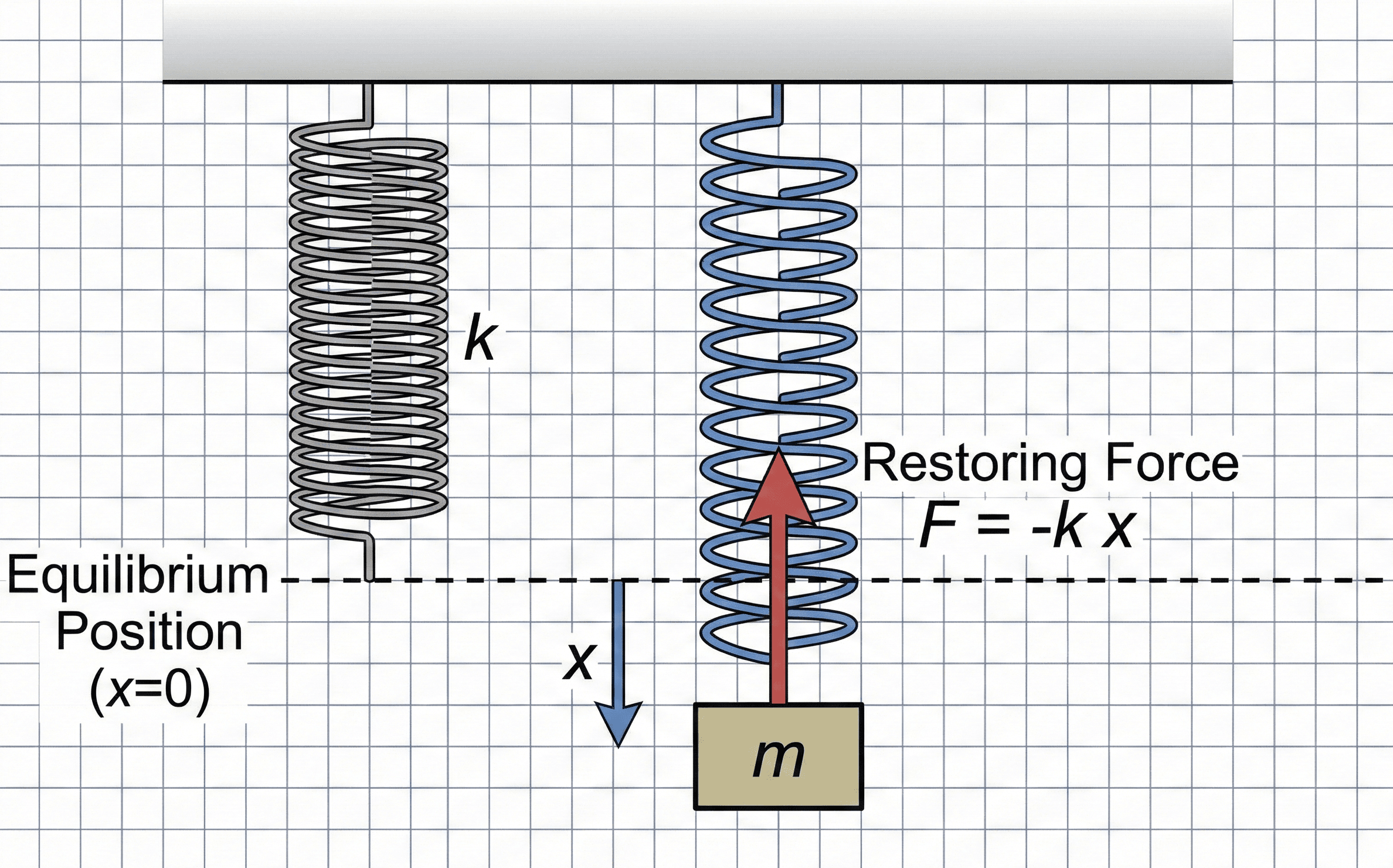

Hooke’s Law states that, within the linear elastic range, the force in a spring is proportional to how far it is stretched or compressed: the stiffer the spring (larger \(k\)), the more force it produces for a given deflection \(x\).

At its core, Hooke’s Law is a linear model of elasticity: double the displacement and you double the force, as long as you stay within the proportional limit of the material. The constant \(k\) is the spring constant or stiffness, and it encodes how hard a spring is to stretch or compress. A large \(k\) means a stiff spring with small deflections under load; a small \(k\) means a soft spring with noticeable deflection under modest forces.

The negative sign in \( F = -k x \) is a reminder that the spring force always points opposite to the displacement: if you pull the free end to the right, the spring pulls back to the left. In many hand calculations and design spreadsheets, engineers work with magnitudes and simply write \( F = k x \), keeping track of directions through sign conventions on the free-body diagram instead.

You can experiment with different loads, deflections, and stiffness values using the Hooke’s Law spring constant calculator to see how \(F\), \(k\), and \(x\) trade off in real design scenarios.

Hooke’s Law also underpins more advanced topics you’ll encounter in mechanics courses and real projects. It leads directly to formulas for stored elastic energy, to equivalent stiffness for springs in series and parallel, and to the natural frequency of a mass–spring system. Once you’re comfortable with the basic relationship, the same idea extends to stress–strain curves, Young’s modulus, and vibration models that treat full structures as sets of equivalent springs.

Symbols, units & notation in Hooke’s Law

In one dimension, Hooke’s Law is usually written as \( F = -k x \), where force \(F\), spring constant \(k\), and displacement \(x\) are all signed quantities. In catalogs and spreadsheets you will also see rearranged forms like \( k = \dfrac{|F|}{|x|} \) when only magnitudes are of interest. The table below summarizes the most common symbols and engineering units used with Hooke’s Law.

Common notation for linear springs

| Symbol | Quantity | SI unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( F \) | Spring force | Newton (N) | Force exerted by the spring on its attachment point. Sign indicates direction relative to the chosen positive axis. |

| \( k \) | Spring constant / stiffness | N/m | Proportionality constant linking force and displacement. Larger \(k\) means a stiffer spring. Catalogs often quote \(k\) in N/mm; \(1~\text{N/mm} = 1000~\text{N/m}\). |

| \( x \) | Displacement from equilibrium | m | Signed displacement from the spring’s unloaded (or defined reference) length. Positive \(x\) is usually taken as extension; negative \(x\) as compression. |

| \( \Delta L \) | Change in length | m | Alternative notation for deflection, \( \Delta L = L – L_0 \). Often used in structural and beam-deflection problems where springs are equivalent to flexible members. |

| \( L_0 \) | Free / reference length | m | Spring length at zero reference force (or at a specified preload). The definition of \(x\) depends on how this reference length is chosen. |

| \( U \) | Elastic potential energy | Joule (J) | Energy stored in the spring when deflected: \( U = \tfrac{1}{2} k x^2 \). This follows directly from integrating Hooke’s Law as displacement increases from 0 to \(x\). |

Unit systems & practical notes

- Use consistent length units: if your spring constant is in N/mm, keep deflection in mm; if you convert deflection to metres, convert \(k\) to N/m as well.

- Direction matters: the negative sign in \( F = -k x \) is about direction, not magnitude. For magnitude-only calculations, \( |F| = k |x| \) is sufficient as long as your free-body diagram tracks signs.

- From springs to materials: in stress–strain form, Hooke’s Law becomes \( \sigma = E \epsilon \), where \(E\) (Young’s modulus) has units of Pa. This is the continuous-material analogue of \(k\) for discrete springs.

Once your symbols and directions are clear, you can apply Hooke’s Law directly in hand calculations or combine it with the worked examples below to sanity-check more complex spring and deflection problems.

How Hooke’s Law models linear elastic behavior

Hooke’s Law is a local, linear approximation of how real springs and elastic materials behave. Near an equilibrium position, many systems respond to small displacements with forces that are almost exactly proportional to displacement. This is why you can treat a wide variety of components as “equivalent springs” around a chosen operating point, even if their full force–deflection curve is more complicated.

The idea is easiest to see on a force–displacement graph. For an ideal linear spring, the curve is a straight line through the origin with slope \(k\). The slope tells you how much extra force you need per unit of additional deflection. As long as the material stays in its elastic range (no permanent deformation), stretching and releasing the spring traces the same line back and forth, and Hooke’s Law holds well.

Rearranging Hooke’s Law & related formulas

Starting from the one-dimensional form of Hooke’s Law,

you can write several equivalent, calculation-friendly versions:

These are what you’ll actually use in design work – computing the force for a given deflection, finding the deflection under a specified load, or back-calculating an effective stiffness from test data. Hooke’s Law also leads directly to the expression for stored elastic energy:

This quadratic dependence on displacement is why doubling the deflection of a spring quadruples the stored energy – an important consideration in safety and impact scenarios.

From single springs to systems & vibration behavior

Real mechanisms rarely contain just one spring. Bellows, mounts, brackets, and beams all contribute to an overall stiffness seen by a moving mass. Hooke’s Law still applies, but you first reduce the system to an equivalent spring constant and then apply \( F = k x \) to that equivalent.

For dynamics, a simple mass–spring system has a natural circular frequency

where \(m\) is the attached mass. Increasing stiffness or reducing mass raises the natural frequency. Although this goes beyond “static” Hooke’s Law, the same linear force–displacement assumption is what makes these vibration formulas possible.

In short, Hooke’s Law is the bridge between material properties, component stiffness, and larger system behavior. It is accurate for small deflections in the elastic range, and it provides a convenient starting point before you resort to nonlinear finite-element models or detailed material testing.

Worked examples using Hooke’s Law

The examples below mirror common Hooke’s Law questions engineers and students search for: calculating spring force from deflection, estimating deflection from a known load, and working out equivalent stiffness for springs in series and parallel. You can adapt the same workflow to real components like mounts, supports, and flexible couplings.

Example 1 – Force from a known spring constant and deflection

A linear compression spring has a stiffness of \( k = 250~\text{N/m} \). In a fixture, it is compressed by \( x = 80~\text{mm} \) from its free length. Assuming the spring stays within its linear range, what is the magnitude of the spring force?

- Convert all lengths to consistent units.

- Apply the magnitude form of Hooke’s Law, \( |F| = k |x| \).

- Interpret the result in the context of the fixture or mechanism.

Result: The spring exerts approximately \(20~\text{N}\) on the fixture when compressed by 80 mm. In a free-body diagram, this force would appear opposite to the direction of compression, consistent with \(F = -k x\).

Example 2 – Deflection of a spring under a specified load

You’re selecting a spring to support a 150 N vertical load in a machine. Catalog data lists a candidate spring with stiffness \( k = 4.0~\text{N/mm} \). If you treat the spring as linear and ignore its own weight, how much will it deflect under the 150 N load, and is that reasonable for a system that can only tolerate 30 mm of movement?

- Convert the stiffness to consistent units if necessary.

- Rearrange Hooke’s Law to solve for deflection: \( x = \dfrac{|F|}{k} \).

- Compare the predicted deflection to the allowable movement.

Result: The spring will deflect about \(37.5~\text{mm}\) under the 150 N load, which exceeds the allowable 30 mm travel. You would need to select a stiffer spring (larger \(k\)) or redesign the support so the load is shared by multiple springs in parallel.

Example 3 – Equivalent stiffness of springs in series and parallel

Two linear springs with stiffnesses \( k_1 = 800~\text{N/m} \) and \( k_2 = 1200~\text{N/m} \) are used in a vibration-isolation system. First, they are mounted in parallel between a base and a mass. Then, as a design variant, they are connected in series between the same base and mass. What is the equivalent stiffness in each case?

For parallel springs, deflection is the same but forces add. For series springs, the force is the same through both springs but deflections add. Hooke’s Law gives standard formulas for each configuration.

Result: In parallel, the springs behave like a single stiffer spring with \( k_{\text{eq}} = 2000~\text{N/m} \). In series, they behave like a much softer spring with \( k_{\text{eq}} \approx 480~\text{N/m} \). This illustrates how the same components can produce very different system behavior depending on configuration.

Design tips, limits & checks when using Hooke’s Law

In real designs, Hooke’s Law is a first-order model. It is excellent for quick estimates, preliminary sizing, and classroom problems, but you should always keep its assumptions in mind. The chips below highlight practical guidelines and common pitfalls when using \( F = -k x \) in engineering work.

Choosing the “right” stiffness is one of the most important decisions in a spring-based design. Too soft, and you get excessive deflection or bottoming out; too stiff, and you transmit high forces, lose isolation, or create uncomfortable user interfaces.

- Start from allowed deflection: rearrange \( x = \dfrac{|F|}{k} \) to estimate the minimum stiffness needed so deflection stays within your envelope.

- Check both operating and extreme loads – springs must not yield or bottom out at maximum load, including shock or misuse cases.

- For vibration isolation, target a low stiffness (low natural frequency) so the system’s natural frequency is well below the excitation frequency.

- Using Hooke’s Law beyond the elastic range, where the force–deflection curve is clearly nonlinear or includes permanent set.

- Mixing N/m with N/mm or inches with millimetres, leading to deflections off by factors of 10–100.

- Ignoring preload and assembly conditions – real springs may already be compressed or stretched at the nominal “zero” condition.

- Applying a single stiffness to complex geometry (like a long flexible bracket) without checking whether bending, buckling, or contact effects dominate.

Even if your math is correct, simple reality checks can catch design issues early.

- Compare predicted deflections to the physical size of the spring or structure – deflections larger than ~20–30% of free length usually indicate you’re past the safe linear-elastic range.

- Use \( U = \tfrac{1}{2} k x^2 \) to estimate stored energy and assess whether a sudden release could be hazardous to users or components.

- If you’re designing for fatigue or repeated cycling, verify that stresses computed from the spring force stay well below endurance or fatigue limits, not just static yield.

When your design is near material limits, involves large deflections, or uses rubber-like materials with strong hysteresis, Hooke’s Law should be treated as a starting point only. At that stage, it’s common to refine the model using measured force–deflection data, manufacturer-provided curves, or nonlinear finite-element analysis instead of relying on \( F = -k x \) alone.

Hooke’s Law – FAQ

What is Hooke’s Law in simple terms?

Hooke’s Law says that the force a spring exerts is proportional to how far it is stretched or compressed, as long as you stay in the elastic range. Double the stretch and you double the force. The constant of proportionality \(k\) tells you how stiff the spring is, and the basic relationship is \( F = -k x \).

What does the negative sign in \( F = -k x \) mean?

The negative sign indicates direction: the spring’s force always acts opposite to the displacement from equilibrium. If you pull the end of the spring in the positive direction, the spring force points in the negative direction, trying to restore the spring to its original length. In many calculations, engineers focus on magnitudes and write \( |F| = k |x| \), while tracking the sign separately in the free-body diagram.

When does Hooke’s Law stop being accurate?

Hooke’s Law is accurate only in the linear elastic range of a spring or material. If you deflect a spring so far that coils touch, material yields, or the force–deflection curve bends noticeably away from a straight line, the relationship \( F = -k x \) no longer holds. Nonlinear behavior is common in rubber, foams, highly stressed metals, and components with complex geometry or contact.

Is Hooke’s Law the same as Young’s modulus or stress–strain relations?

Hooke’s Law for springs, \( F = -k x \), is a discrete version of the same idea as the material-level relation \( \sigma = E \epsilon \), where \( \sigma \) is stress, \( \epsilon \) is strain, and \(E\) is Young’s modulus. In one dimension, you can think of \(k\) as the effective stiffness of a particular component, while \(E\) describes the intrinsic stiffness of the material it is made from. Both are linear models valid only in the elastic range.

References & further reading

- Standard mechanics of materials textbooks, which introduce Hooke’s Law, stress–strain diagrams, and the connection between spring constants and Young’s modulus.

- Classical mechanics and vibrations texts, which extend Hooke’s Law to mass–spring systems, simple harmonic motion, and equivalent stiffness for complex structures.

- Spring manufacturer catalogs and application notes, which provide real-world force–deflection curves, recommended operating ranges, and design guidance for coil, torsion, and leaf springs.