Electrical Engineering · Maxwell’s Equation

Maxwell’s Equation – unifying electric & magnetic fields

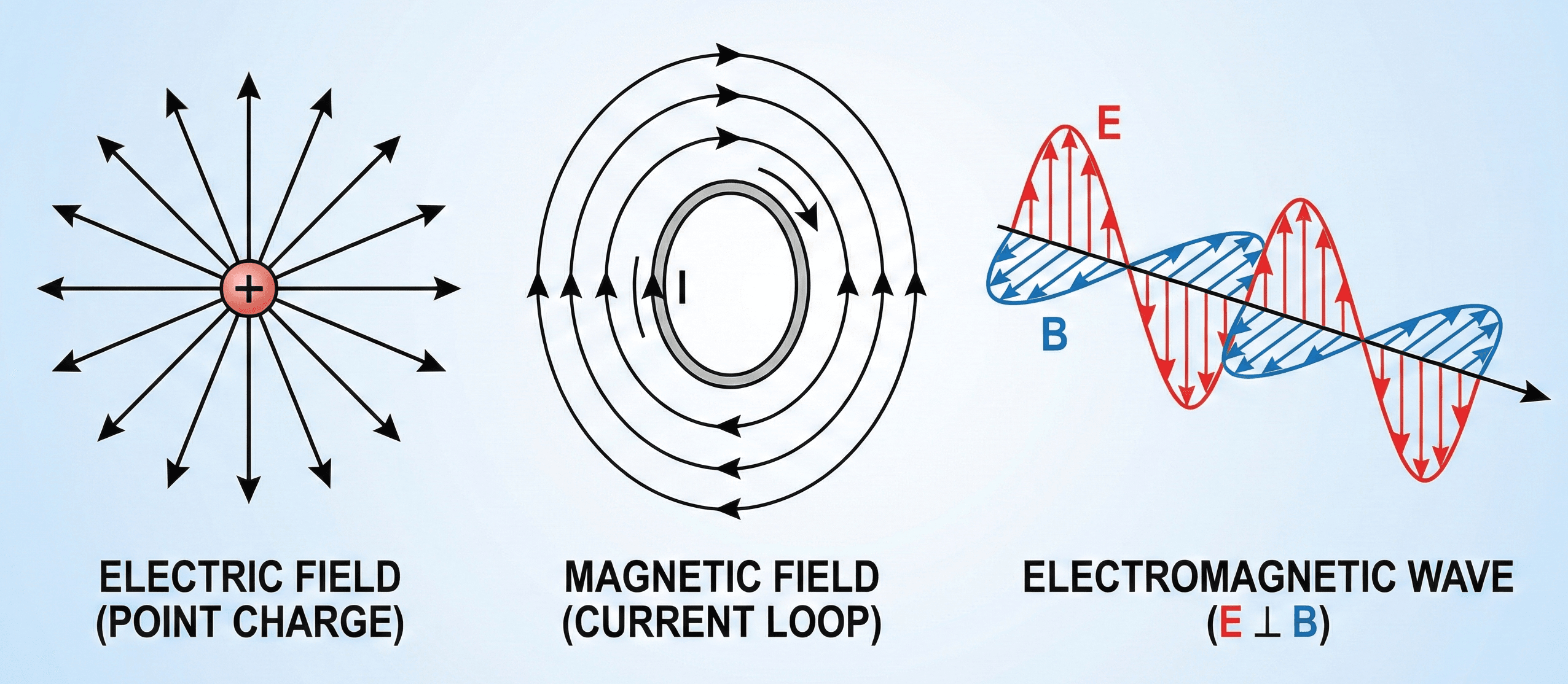

Maxwell’s Equation (usually written as Maxwell’s equations) ties together electric fields, magnetic fields, charge, and current, giving you the complete set of differential laws that govern classical electromagnetism, wave propagation, and most RF, antenna, and high-speed circuit behavior.

Quick answer: what Maxwell’s Equation tells you

Core set of equations (differential form)

Maxwell’s Equation is really a compact name for four coupled vector equations that describe how electric fields, magnetic fields, charge density, and current density evolve in space and time – and from them you get everything from static fields around conductors to radio waves in free space.

At the engineering level, Maxwell’s Equation answers, in a unified way, “What fields do my charges and currents create?” and “How do changing fields generate new fields?”. The first pair, Gauss’s law for electricity and Gauss’s law for magnetism, constrain how field lines start and end: electric field lines begin and end on charge, while magnetic field lines form continuous loops with no isolated magnetic monopoles. The second pair, Faraday’s law and the Ampère–Maxwell law, describe how changing magnetic fields generate electric fields and how currents plus changing electric fields generate magnetic fields.

In simple DC circuits you can often get away with lumped approximations like Ohm’s Law and Kirchhoff’s laws. But as structures get electrically large (high frequency, long traces, antennas, high-speed digital links), Maxwell’s Equation becomes the real governing model underneath your simulations, field solvers, and design rules. It explains wave propagation, impedance, skin effect, radiation, and why “ground” is never truly at the same potential everywhere.

Field symbols, constants & units in Maxwell’s Equation

Maxwell’s Equation is typically written in differential vector form, as shown above, or in integral form over surfaces and loops. In either case, the same core symbols appear again and again. The table below summarizes the most common quantities, their physical meaning, and standard SI units for engineering work.

Common field quantities & sources

| Symbol | Quantity | SI unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( \vec{E} \) | Electric field intensity | V/m | Force per unit charge acting on a small positive test charge. Lines point from positive to negative potential. |

| \( \vec{D} \) | Electric flux density | C/m² | Also called electric displacement field; relates to \( \vec{E} \) via material permittivity: \( \vec{D} = \varepsilon \vec{E} \) in linear media. |

| \( \vec{B} \) | Magnetic flux density | T (tesla) | Magnetic field that appears in the Lorentz force \( \vec{F} = q(\vec{E} + \vec{v} \times \vec{B}) \); sometimes called “magnetic field” in engineering contexts. |

| \( \vec{H} \) | Magnetic field intensity | A/m | Related to \( \vec{B} \) via permeability: \( \vec{B} = \mu \vec{H} \) in linear media; more directly tied to current distributions. |

| \( \rho \) | Volume charge density | C/m³ | Electric charge per unit volume; acts as a source term in Gauss’s law for electricity. |

| \( \vec{J} \) | Current density | A/m² | Conduction current per unit cross-sectional area; appears in the Ampère–Maxwell law as a source of magnetic fields. |

| \( \varepsilon_0 \) | Permittivity of free space | F/m | Constant relating electric field to charge density in vacuum; approximately \( 8.854 \times 10^{-12}~\text{F/m} \). |

| \( \mu_0 \) | Permeability of free space | H/m | Constant relating magnetic field to current in vacuum; approximately \( 4\pi \times 10^{-7}~\text{H/m} \). |

| \( \nabla \cdot \) | Divergence operator | 1/m | Measures how much a vector field “spreads out” from a point; used in Gauss’s laws. |

| \( \nabla \times \) | Curl operator | 1/m | Measures circulation or “twist” of a vector field; used in Faraday’s law and the Ampère–Maxwell law. |

Unit systems & notation tips

- SI is the default in engineering: use volts, amperes, meters, farads, henries, etc. Avoid mixing with cgs (Gaussian) units unless a source explicitly uses them.

- In linear, isotropic media, you often write \( \varepsilon = \varepsilon_r \varepsilon_0 \) and \( \mu = \mu_r \mu_0 \), where \( \varepsilon_r \) and \( \mu_r \) are relative permittivity and permeability.

- Many textbooks write Maxwell’s Equation in terms of \( \vec{D} \) and \( \vec{H} \) instead of \( \vec{E} \) and \( \vec{B} \) for materials. Be explicit about which convention you are using when comparing formulas.

Once the symbols are clear, the next step is to connect Maxwell’s Equation to the kind of fields or waves you care about – static capacitor fields, inductor flux, or full EM waves – and then simplify to forms that are easier to solve in that regime.

How Maxwell’s Equation ties charges, currents & fields together

The power of Maxwell’s Equation is that it compresses all classical electromagnetism into four local relationships. Each equation has a specific physical role, and common engineering problems usually emphasize just one or two of them in a simplified geometry. Thinking of them conceptually makes it easier to know which form you actually need.

Gauss’s laws – where field lines start and end

The first two equations are Gauss’s laws for electric and magnetic fields:

The divergence of \( \vec{E} \) is proportional to charge density: positive charge is a source of field lines, negative charge is a sink. In integral form, this becomes “electric flux through a closed surface equals enclosed charge over \( \varepsilon_0 \)”, which you use heavily in capacitor and high-voltage insulation design. The second law simply says that magnetic field lines never start or stop; they always form loops, which is why you do not design around isolated “north” or “south” magnetic charges.

Faraday & Ampère–Maxwell – how changing fields generate new fields

The other two equations describe induction and magnetostatics, plus the critical displacement current term:

Faraday’s law says that a changing magnetic field induces a circulating electric field – the basis of transformers, generators, and any time-varying mutual inductance. The Ampère–Maxwell law says that both conduction current \( \vec{J} \) and changing electric field \( \partial \vec{E}/\partial t \) create circulating magnetic fields. That extra displacement current term is what makes capacitor currents and electromagnetic waves consistent with charge conservation.

From Maxwell’s Equation to wave equations & circuit models

Combining Faraday’s law with the Ampère–Maxwell law in a source-free, homogeneous medium yields the electromagnetic wave equation. In vacuum, you get:

The wave speed that drops out is \( c = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{\mu_0 \varepsilon_0}} \), which numerically matches the speed of light. This is the famous result that shows light is an electromagnetic wave. In guided structures like coax, microstrip, or rectangular waveguides, you solve modified forms of the same wave equations with boundary conditions set by conductors and dielectrics.

In most practical designs, you do not start from the full differential equations by hand. Instead, you use them to derive simplified models: lumped RLC circuits, transmission-line equations, or field solver setups. Knowing which Maxwell term dominates (for example, displacement current vs. conduction current, or static vs. time-varying fields) helps you choose the right approximation and understand when a “simple circuit” view breaks down.

Worked examples using Maxwell’s Equation

The examples below show how you apply Maxwell’s Equation in common engineering situations – first in a static field problem, then in a wave-propagation scenario, and finally in an induction setup. Each example mirrors the kind of question students and engineers actually search for when they are trying to connect the theory to real components.

Example 1 – Electric field between ideal parallel plates

Two large parallel plates form an air-gap capacitor with plate area \( A = 0.020~\text{m}^2 \) and separation \( d = 1.0~\text{mm} \). A DC voltage of \( V = 500~\text{V} \) is applied between the plates (top plate positive). Assuming fringe effects are negligible, find: (a) the approximate electric field between the plates, and (b) the surface charge density on each plate.

- Approximate the field as uniform between the plates and relate it to applied voltage.

- Use Gauss’s law in integral form to relate electric flux to enclosed charge.

- Relate the flux density and field to surface charge density.

Result: The electric field magnitude between the plates is about \( 5.0 \times 10^{5}~\text{V/m} \), and the surface charge density on each plate is approximately \( 4.4~\mu\text{C/m}^2 \). This is a direct use of Gauss’s law, simplified by symmetry for an essentially one-dimensional field.

Example 2 – Wave speed from Maxwell’s Equation

Using Maxwell’s Equation in free space, show how the speed of electromagnetic waves depends on \( \mu_0 \) and \( \varepsilon_0 \), and evaluate the numerical value. This is a common conceptual question: “How does Maxwell’s Equation imply the speed of light?”.

- Start with Faraday’s law and the Ampère–Maxwell law in a charge-free, current-free region.

- Take the curl of Faraday’s law and substitute from the Ampère–Maxwell law.

- Recognize the resulting wave equation and identify the wave speed.

Result: Maxwell’s Equation predicts that electromagnetic waves in vacuum propagate at \( c = 1/\sqrt{\mu_0 \varepsilon_0} \), which numerically matches the measured speed of light. This is one of the most important conceptual links between electromagnetism and optics.

Example 3 – Induced EMF in a changing magnetic field

A circular coil with \( N = 200 \) turns and radius \( r = 5.0~\text{cm} \) is placed in a uniform magnetic field perpendicular to its plane. The magnetic flux density increases linearly from \( 0.02~\text{T} \) to \( 0.10~\text{T} \) over \( 25~\text{ms} \). What is the magnitude of the average induced EMF in the coil?

- Write Faraday’s law in integral form for the coil, including the number of turns.

- Compute the change in flux per turn from the change in magnetic field.

- Divide by the time interval to find the average induced EMF.

Result: The coil experiences an average induced EMF of about \( 5~\text{V} \) during the field change. This is a direct application of Faraday’s law, one of the four Maxwell equations, and is representative of how transformers and inductive charging systems behave.

Design tips, limits & checks when using Maxwell’s Equation

In practice, you rarely solve Maxwell’s Equation in full generality by hand. Instead, you exploit symmetry, approximations, and numerical tools. Still, knowing the underlying assumptions and patterns helps you make better decisions when choosing models, interpreting simulator outputs, or performing quick back-of-the-envelope checks.

At low frequencies and small geometries (relative to wavelength), you can treat conductors and components as lumped elements and rely mainly on Ohm’s Law, Kirchhoff’s laws, and basic capacitor/inductor formulas. As trace lengths approach a significant fraction of a wavelength or rise times become very fast, distributed effects governed by Maxwell’s Equation dominate.

- Rule of thumb: if trace length is > ~\(\lambda / 10\) or rise time is very sharp, treat interconnects as transmission lines.

- Parasitic inductance and capacitance come directly from field solutions; ignoring them can cause ringing, EMI, and logic errors.

- Verify that your chosen model (lumped vs. distributed) is consistent with the physical scale and frequency content of the signals.

- Mixing quasi-static formulas with high-frequency situations where wave propagation and radiation are important.

- Ignoring boundary conditions at interfaces (for example, between different dielectrics or between conductor and air), which are derived from Maxwell’s Equation and strongly influence field distributions.

- Assuming magnetic monopoles or “broken” field lines, which violates \( \nabla \cdot \vec{B} = 0 \) and leads to inconsistent reasoning.

Whether you’re using a full-wave solver, a simplified analytical expression, or a spreadsheet, there are a few quick checks that can help you spot errors before they become design issues.

- Check that Gauss’s law is satisfied approximately: does the net flux of \( \vec{D} \) through a surface match the enclosed charge within numerical tolerance?

- Verify that calculated wave speeds and impedances make physical sense (for example, propagation velocity in a dielectric should be less than \( c \)).

- Ensure that Poynting vector direction and power flow match intuition: energy should propagate away from sources and toward loads, not the other way around.

As designs push into mmWave, high-speed serial links, and dense power electronics, field-based reasoning becomes essential. Maxwell’s Equation provides the conceptual “grounding” for why design rules and EMC guidelines look the way they do; using it as a mental checklist can keep you from misapplying low-frequency shortcuts.

Maxwell’s Equation – FAQ

What are Maxwell’s equations in simple terms?

In simple language, Maxwell’s equations say: (1) electric charges create electric fields, (2) there are no isolated magnetic charges, only loops of magnetic field, (3) changing magnetic fields create electric fields, and (4) currents and changing electric fields create magnetic fields. Together, these rules fully describe how classical electromagnetic fields behave in space and time.

How do engineers actually use Maxwell’s Equation?

Engineers rarely write all four equations out in full for every problem. Instead, they simplify them based on geometry and frequency to get formulas for capacitance, inductance, skin depth, transmission-line behavior, and radiation. Field solvers and EM simulators solve Maxwell’s Equation numerically under the hood, while designers interpret the results in terms of voltages, currents, and component values.

What is the difference between differential and integral forms of Maxwell’s Equation?

The differential form expresses Maxwell’s Equation at a point in space using operators like divergence and curl. The integral form expresses the same physics over finite surfaces and loops, relating field fluxes and circulations to total enclosed charge and current. For symmetric problems and hand calculations, the integral form is often easier to use; for numerical methods and local reasoning, the differential form is more natural.

When do I need full Maxwell equations instead of simple circuit laws?

If your structures are electrically small and frequencies are low, lumped circuit laws like Ohm’s Law and Kirchhoff’s laws are usually sufficient. When wavelengths become comparable to your geometry, rise times are very fast, or radiation and coupling between conductors matter, you need Maxwell’s Equation (often via transmission-line theory or full-wave simulation). High-speed digital design, RF, antennas, and EMC problems all fall into this category.

References & further reading

- Standard electromagnetics textbooks (for example, “Engineering Electromagnetics” or “Classical Electrodynamics”) for rigorous derivations of Maxwell’s Equation and boundary conditions.

- RF and microwave engineering texts that derive transmission-line models, waveguides, and antenna behavior directly from Maxwell’s Equation for practical design work.

- Documentation for EM field solvers and PCB tools, which often include application notes showing how Maxwell’s Equation underlies impedance control, EMC rules, and high-speed interconnect guidelines.