Key Takeaways

- Definition: Traffic Flow Theory explains how vehicles move collectively using relationships between speed, flow, and density.

- Application: Engineers use it to estimate capacity, diagnose congestion, and evaluate operations on freeways, arterials, and intersections.

- Outcome: You’ll learn how to read the fundamental diagram, interpret breakdown, and understand why congestion waves travel upstream.

- Context: These ideas underpin the Highway Capacity Manual approach and many day-to-day transportation engineering decisions.

Table of Contents

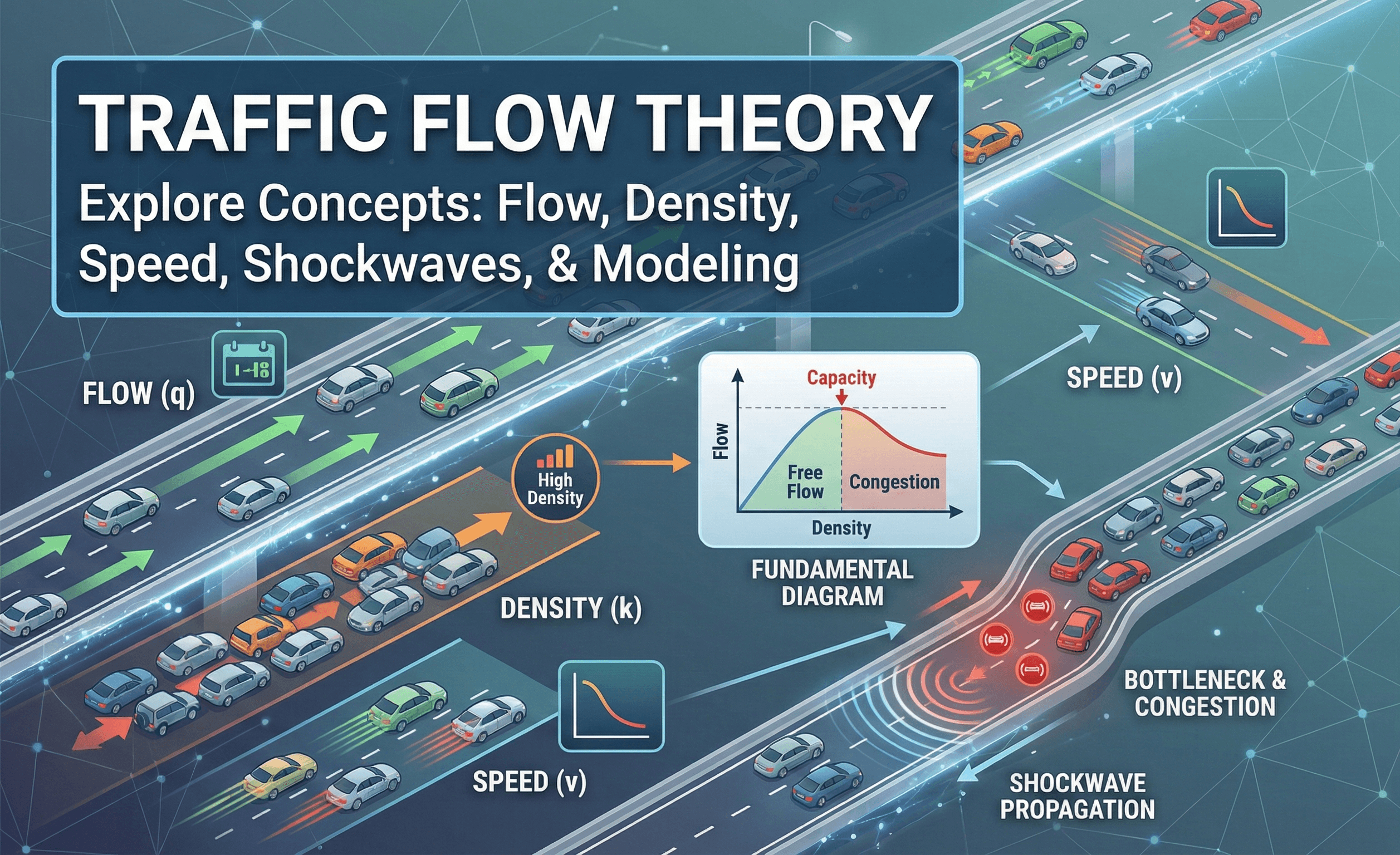

Featured diagram

Introduction

If you clicked a page titled Traffic Flow Theory, you’re probably looking for the “why” behind everyday traffic behavior: why traffic slows down before a bottleneck, why stop-and-go waves appear with no crash, and how engineers estimate capacity and performance. Traffic Flow Theory answers those questions by describing traffic as a system with measurable properties—speed, density, and flow—and by showing how those properties change as demand rises and roadway conditions vary.

This resource is written for engineering students and practicing transportation engineers who want a clear, useful explanation that connects classroom theory to real projects. You’ll learn the core variables and units, how to interpret the fundamental diagram, what “breakdown” means operationally, and how congestion waves (shockwaves) propagate. Along the way, you’ll see practical checks engineers use to keep numbers realistic, plus where these ideas show up in common references like the Highway Capacity Manual.

What is Traffic Flow Theory?

Traffic Flow Theory is the study of how vehicles move collectively on a transportation facility, using relationships between measurable traffic variables. Instead of analyzing one driver at a time, it focuses on the overall behavior of a traffic stream: how traffic performs under light demand, how it approaches capacity, how it breaks down into congestion, and how disturbances travel through the stream.

In practice, Traffic Flow Theory gives engineers a framework to answer questions like: “How close are we to capacity?”, “What happens if demand increases by 10%?”, “Why does average speed collapse after breakdown?”, and “How will congestion spread if an upstream on-ramp releases vehicles faster?” It also builds the intuition behind common operational terms such as free-flow speed, capacity, queue, spillback, and shockwave.

You’ll see the core variables (speed, density, flow), how they relate, and how engineers interpret “the shape” of traffic behavior. This is not a derivation-heavy textbook chapter—it’s a practical guide for understanding what the models mean and how they’re used.

Core variables, units, and the one relationship you must know

Nearly every traffic flow concept traces back to three variables: flow, speed, and density. Engineers measure or estimate these in both US customary and SI units.

- q Flow (volume rate): vehicles/hour (veh/h) or vehicles/hour/lane (veh/h/ln)

- v Mean speed: miles/hour (mph) or kilometers/hour (km/h)

- k Density: vehicles/mile/lane (veh/mi/ln) or vehicles/km/lane (veh/km/ln)

This relationship is powerful because it forces consistency: if density rises (more vehicles packed into the roadway), either speed drops or flow must change. It also helps you sanity-check field data. For example, if you see very high density and very high speed reported at the same time, something is likely off (measurement location mismatch, data aggregation issue, or a unit problem).

Time-mean speed vs. space-mean speed (why the distinction matters)

In real data, “average speed” can mean different things. Time-mean speed is the average of spot speeds measured at a point (like a detector). Space-mean speed is the average speed over a road segment (often derived from travel time). For many operational calculations, space-mean speed is more representative of how traffic is moving across a facility.

When comparing a model result to field conditions, check whether the “speed” source is point-based (spot speed) or segment-based (travel time). Mixing them can make a correct model look wrong—or a wrong model look correct.

The fundamental diagram: how Traffic Flow Theory “looks”

The fundamental diagram is the most recognizable idea in Traffic Flow Theory. It describes how traffic variables relate as conditions change, typically shown with three paired plots: flow vs. density, speed vs. density, and speed vs. flow. You don’t need to memorize every curve shape, but you do need to understand the story the curves tell.

Free-flow, capacity, and congested regimes

At low density, vehicles can travel close to their desired speed. As density increases, vehicles interact more (following distance decreases, lane changes cause friction), and the system approaches a maximum sustainable flow—capacity. Past that point, additional demand tends to trigger breakdown: speeds drop sharply and flow can decrease even as density continues rising.

| Regime | What you observe | What it implies | Typical engineering use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Free-flow | High speeds, low density, stable movement | Demand is below operational limit | Free-flow speed estimation, planning-level screening |

| Near capacity | High flow, increasing interactions, sensitivity to disturbances | Small disruptions can cause breakdown | Reliability analysis, bottleneck diagnosis |

| Congested | Lower speeds, higher density, stop-and-go waves | Throughput may drop (capacity drop) | Queue management, incident response, operational strategies |

A simple model often used for intuition (Greenshields form)

Many textbooks introduce a linear speed–density model to build intuition. Real traffic isn’t perfectly linear, but the concept helps explain the direction of change: speed decreases as density increases.

- v_f Free-flow speed (mph or km/h): the speed under low density conditions

- k_j Jam density (veh/mi/ln or veh/km/ln): density when traffic is essentially stopped

Combining \(q = k v\) with the linear speed–density form yields a parabolic flow–density curve that rises to a maximum (capacity) and then falls in congestion:

Treating “capacity” as a single fixed value everywhere. Capacity depends on geometry, heavy vehicles, grades, lane drops, weather, incidents, driver population, and control (signals/ramp metering). In Traffic Flow Theory, capacity is best understood as a property of a location and conditions.

Breakdown, queues, and why congestion can appear “out of nowhere”

One of the most useful outcomes of Traffic Flow Theory is explaining breakdown—the transition from stable, near-capacity flow to congested flow. When demand is close to the facility’s operational limit, small disturbances can amplify: brief braking, a tight merge, a lane change, or a slight reduction in discharge flow at a bottleneck can trigger a speed collapse and a growing queue.

Capacity drop (why flow can decrease after congestion starts)

After breakdown, the maximum discharge flow from a congested bottleneck is often lower than the pre-breakdown capacity. This phenomenon, known as capacity drop, is one reason congestion can be hard to “recover” from even if demand decreases slightly. Operational strategies like ramp metering, incident management, and speed harmonization are often aimed at preventing breakdown rather than “fixing” it after the fact.

If your analysis shows sustained flow above a realistic capacity for long periods, check detector quality, aggregation interval, and whether the “flow” is being reported per lane or for the whole facility. Many apparent anomalies are data-definition issues.

Spillback and network effects

Queues are not just a freeway problem. On arterials, queues can spill back into upstream intersections, blocking driveways and side streets and reducing network throughput. Traffic Flow Theory helps you reason about this by connecting density growth (queue formation) to available storage and by describing how congestion propagates across connected facilities.

Shockwaves: how congestion waves move upstream

If you’ve ever watched stop-and-go traffic, you’ve seen a hallmark of Traffic Flow Theory: waves of slowing and accelerating that travel backward (upstream) through the traffic stream. These are commonly called shockwaves or kinematic waves. They occur when two traffic states meet, such as free-flow traffic encountering the back of a queue.

A widely used wave-speed relationship compares two states (1 and 2) using their flow and density values. The wave speed tells you how fast the boundary between those states moves along the roadway:

Interpreting \(w\) is the key: a negative value means the wave moves upstream (typical for the back of a queue), while a positive value means it moves downstream. Engineers use this concept to estimate how quickly a queue will grow and whether it will reach upstream ramps or intersections.

If you can estimate two states from detector data (upstream free-flow vs. downstream congested), shockwave speed gives you a practical way to estimate queue growth and the time-to-spillback—often more useful than debating “exact” model parameters.

Macroscopic vs. microscopic models: choosing the right lens

Traffic Flow Theory spans multiple modeling approaches. The “right” approach depends on what decision you’re trying to make and what data you have. It’s common to combine lenses: use macroscopic relationships for screening and capacity reasoning, then use microscopic simulation for detailed operational design.

Macroscopic (aggregate) approach

Macroscopic models treat traffic like a continuous stream. Inputs and outputs are often aggregate: flow rates, average speeds, density estimates, and the effect of bottlenecks. This approach is typically best for corridor-level reasoning, reliability insights, and capacity/performance assessment.

Microscopic (vehicle-based) approach

Microscopic models represent individual vehicles and their interactions (car-following, lane-changing, gap acceptance). They’re useful when geometry, control, and driver behavior details matter—like merge areas, weaving segments, and intersection operations.

If you need “how much” (capacity, throughput, speed), start macroscopic. If you need “how” (conflicts, merges, queue interactions by lane), go microscopic.

How engineers apply Traffic Flow Theory in real projects

The most useful way to learn Traffic Flow Theory is to see how it shows up in everyday work. A common workflow looks like this:

- Define the facility and question: freeway segment, bottleneck, arterial, or intersection; capacity concern, queue concern, or performance concern.

- Collect or estimate traffic states: flows, speeds, and occupancy/density proxies (detectors, probe data, counts, turning movements).

- Identify regimes and constraints: free-flow vs near-capacity vs congested; geometry constraints (lane drops, merges), control constraints (signals, ramp meters).

- Use theory to interpret behavior: read the fundamental diagram logic; locate likely breakdown points; understand shockwave direction and spillback risk.

- Evaluate countermeasures: demand management, metering, signal timing, geometric changes, or operational strategies.

- Validate with field reality: compare to observed travel times, queue lengths, and bottleneck locations; refine assumptions and document limitations.

Treating short-term “peaks” in measured flow as sustainable capacity. In near-capacity conditions, brief surges can occur due to platoons or detector noise, but sustained performance depends on stability and downstream discharge behavior.

Worked example: interpreting a traffic state with the fundamentals

Example

Suppose a freeway lane is observed to carry \(q = 1{,}800\) veh/h/ln at an average speed of \(v = 45\) mph. Estimate the density and interpret whether the condition is likely free-flow or approaching congestion (conceptually).

A density of 40 veh/mi/ln indicates substantial interaction between vehicles. Whether it’s “congested” depends on local free-flow speed, facility type, and how close you are to the critical density where maximum flow occurs. The engineering takeaway is that this state is not “empty-road” free-flow; it’s a condition where small disturbances can begin to matter, especially near known bottlenecks.

Always pair your computed density with the context: how many lanes, heavy-vehicle percentage, grades, and whether there is a downstream merge or lane drop. The same computed density can behave differently depending on bottleneck sensitivity.

Common mistakes and quick engineering checks

Traffic Flow Theory becomes “useful” when it helps you avoid wrong conclusions. Here are the most common failure modes engineers see in practice:

- Unit inconsistency: mixing veh/hr with veh/min, or density per lane vs per facility.

- Misreading detectors: occupancy is not density unless calibrated; aggregation intervals matter.

- Ignoring regime changes: using a free-flow relationship when the system is congested (or vice versa).

- Assuming capacity is constant: weather, incidents, driver behavior, and lane-blocking events change the effective capacity.

- Forgetting the network: downstream signals or spillback can cap throughput even if the upstream segment “looks” fine.

| What you computed | What to verify | Why it matters | Quick check |

|---|---|---|---|

| High flow and high speed | Per-lane vs total flow, detector health | Implausible states often come from definitions | Confirm lanes and aggregation period |

| Density from occupancy | Calibration assumptions | Occupancy varies by vehicle length and speed | Compare to probe travel time |

| Queue growth estimate | Downstream discharge stability | Capacity drop changes how fast queues grow | Use observed discharge rates if possible |

When you compute a traffic state, always write it as \((q, v, k)\) with units. If you can’t state the units clearly, the result isn’t ready for design decisions.

Relevant standards and design references

Traffic Flow Theory shows up directly in the references transportation engineers use to define performance, capacity, and operational quality. These are the most common places you’ll see the theory operationalized into procedures, default values, and accepted methods.

- Highway Capacity Manual (HCM): Core reference for capacity and operational analysis; connects flow, speed, density, and performance measures like LOS.

- FHWA operations guidance: Practical guidance on congestion management, freeway operations, ramp metering, and performance measurement using traffic state concepts.

- AASHTO “Green Book”: Geometric design context that influences free-flow speed, bottleneck formation, and operating performance.

- MUTCD: Traffic control standards; while not a traffic flow textbook, it affects driver behavior and operations through signing, markings, and control devices.

Frequently asked questions

Traffic Flow Theory is used to relate speed, flow, and density so engineers can estimate capacity, interpret congestion and breakdown, and evaluate operational performance on highways, arterials, and intersections.

When traffic is near capacity, small disturbances like brief braking or lane changes can amplify, producing stop-and-go waves that propagate upstream as a shockwave even without an incident.

The fundamental diagram describes how flow, density, and speed relate, showing free-flow behavior at low density, a maximum flow at capacity, and reduced flow under congested conditions.

Most practical work uses algebra, careful units, and basic rate concepts; more advanced calculus and differential equations mainly appear in higher-level kinematic-wave and research models.

Macroscopic models treat traffic as an aggregate flow using variables like density and flow, while microscopic models represent individual vehicle interactions such as car-following and lane-changing behavior.

Summary and next steps

Traffic Flow Theory gives transportation engineers a clean way to think about what traffic is doing and why. By framing traffic as a system described by speed, density, and flow, the theory explains the transition from free-flow to congestion, the meaning of capacity, and the upstream movement of congestion waves. When you can describe a facility using traffic states and regimes, you can diagnose bottlenecks faster and make better decisions about operations and design.

For students, the biggest win is learning to interpret the fundamental diagram and connect equations to physical behavior. For practicing engineers, the biggest win is using theory to avoid wrong conclusions from messy field data—especially near capacity where small disturbances can dominate. If you remember only one thing, remember that near-capacity traffic is fragile, and preventing breakdown is often more effective than trying to “fix” congestion after it starts.

Next, deepen your understanding by linking these ideas to capacity procedures, control strategies, and facility-specific analysis methods within Transportation Engineering.

Where to go next

Continue your learning path with these curated next steps.

-

Highway capacity analysis

See how capacity and operational performance measures are computed and interpreted for common facility types.

-

Traffic signal operations

Connect flow concepts to saturation flow, queues, progression, and intersection performance.

-

Transportation Engineering hub

Browse more transportation resource pages and build your study path from fundamentals to applied design.