Key Takeaways

- Definition: Highway design is the geometric and functional layout of roadways\u2014alignment, cross-section, sight distance, and roadside features\u2014so drivers can travel safely and comfortably at a chosen design speed.

- Application: Transportation engineers apply highway design principles on projects ranging from rural two-lane upgrades to complex interchanges, balancing safety, capacity, cost, and environmental constraints.

- Outcome: After reading this guide, you will understand core highway design elements, the key equations behind stopping sight distance and curves, and the standards that govern real-world design decisions.

- Context: Highway design sits at the intersection of geometric design, traffic engineering, safety, and pavement/drainage, and is a core topic in most transportation engineering curricula.

Table of Contents

Featured diagram

Introduction

Highway design is where transportation engineering becomes tangible: it is the process of translating traffic forecasts, safety goals, and environmental constraints into a physical roadway that drivers experience every day. A well-designed highway feels intuitive and forgiving. Curves match driver expectations, signs and markings are easy to interpret, and the road performs reliably in good weather and bad. A poorly designed highway, on the other hand, can feel confusing, tiring, or even dangerous.

This guide walks through the core elements of highway design, from design speed and horizontal alignment to cross-sections, sight distance, and roadside safety. We will highlight the key equations behind stopping sight distance and curves, show how traffic volumes feed into design decisions, and anchor everything in the standards that practicing engineers use, such as the AASHTO Green Book and the Highway Capacity Manual. Whether you are a student, hobbyist, or practicing engineer, the goal is to give you enough depth to understand the why behind the geometry you see on real projects.

What is highway design in transportation engineering?

Highway design is the discipline of shaping the three-dimensional geometry and roadside environment of roads so that users can travel safely, comfortably, and efficiently at a selected design speed. It includes the layout of horizontal and vertical curves, lane and shoulder widths, medians, intersections and interchanges, roadside slopes, barriers, and drainage features. At its core, highway design tries to predict how people will drive and then provides enough guidance, space, and forgiveness to keep them within a safe operating envelope.

In a typical project workflow, traffic engineers estimate future volumes, vehicle mixes, and turning movements; planners identify corridors and cross-sections that fit broader network and land-use goals; and highway designers convert all that into detailed plans and profiles. You will see highway design concepts in courses like geometric design, transportation planning, and traffic safety, and in field work whenever a road is widened, realigned, or reconstructed. On the job, you use the same principles whether you are designing a rural two-lane highway or adding auxiliary lanes to a congested urban freeway.

Key design drivers, variables, and units

Before drawing a single curve, highway designers establish a handful of key parameters that drive nearly every geometric decision. These include the design speed, the design vehicle, the design traffic volumes, and the terrain and roadside environment. Each parameter has associated variables and units that appear repeatedly in design equations and checks.

Key variables and typical ranges

The variables below show up across sight distance, curve design, and cross-section decisions. Exact values depend on whether you are working in metric or U.S. customary units; this guide uses SI units for equations unless noted otherwise.

- V Design speed (km/h or m/s). Typical freeway values: 80–120 km/h. Urban arterials: 50–80 km/h.

- t Perception–reaction time (s). Commonly 2.0–2.5 s for design of stopping sight distance.

- g Acceleration due to gravity (9.81 m/s² in SI design).

- f Coefficient of longitudinal friction between tires and pavement (dimensionless). Often 0.30–0.40 for dry pavement at highway speeds.

- G Grade of the roadway (decimal). Positive for upgrades, negative for downgrades; typical design grades: ±2–6%.

- R Radius of a horizontal curve (m). Higher speeds require larger radii to keep lateral acceleration comfortable.

When reviewing a set of highway plans, do a quick sanity check on the combination of design speed, radius, and grade. If a curve looks tight for the posted speed or grades exceed what you expect for the terrain, it is worth double-checking that the correct values were used in the design checks and that the assumptions still match current standards.

Key highway design equation: stopping sight distance

Many geometric decisions ultimately come back to one simple question: can a driver see far enough ahead to stop safely if something unexpected appears in the roadway? The stopping sight distance (SSD) equation captures this by combining perception–reaction time and braking distance into a single required length along the roadway.

In this form, SSD is the minimum distance required for a driver traveling at speed V (m/s) to perceive a hazard, react, and bring the vehicle to a stop on a grade G, given a friction coefficient f and gravity g. The first term, \(V t\), is the perception–reaction distance. The second term, \(\frac{V^2}{2 g (f + G)}\), is the braking distance. Designers compare this required SSD to the available sight distance on tangents and curves; if the available distance is less than SSD, the geometry must be adjusted or mitigations (signing, speed management, barriers) considered.

In U.S. customary practice, the same concept appears in slightly different forms with speed in mph and SSD in feet, but the underlying physics is identical. The important point is that SSD increases rapidly with speed, which is why seemingly small changes in posted speed can drive significant changes in curve layout, crest vertical curves, and roadside clear zones.

Highway design workflow from concept to plans

Although every agency and consultant has its own templates, most highway design workflows follow a similar set of stages. As you work through them, you will move from coarse decisions about alignment and cross-section to detailed checks of every curve and roadside element.

- Define context and performance goals. Establish project limits, functional classification, design speed, access expectations, and multimodal needs (freight, transit, bikes, pedestrians).

- Lay out preliminary alignment and cross-section. Select a corridor, then sketch horizontal and vertical alignments, lane and shoulder widths, medians, and side slopes for each segment.

- Check sight distance and curvature. Apply stopping and passing sight distance checks, verify horizontal curve radii and superelevation, and design crest/sag vertical curves to meet comfort and visibility criteria.

- Detail intersections, interchanges, and access. Design ramp terminals, left-turn lanes, tapers, channelization, and access management features, including driveways and frontage roads.

- Integrate drainage, structures, and utilities. Coordinate cross-drainage, culverts, bridges, and retaining structures with the highway geometry; ensure that inlets, ditches, and barriers fit the design.

- Refine plans and verify constructibility. Run final checks on cross-sections, earthwork, clear zones, and safety hardware, then produce plan/profile sheets, typical sections, and detail sheets for construction.

Experienced highway designers mentally walk the roadway in both directions and imagine driving at the design speed in day and night, wet and dry conditions. They look for sudden changes in curvature, inconsistent lane drops, awkward sight lines at ramps or intersections, and conflicts between roadside objects and clear zones. If something would surprise them as a driver, it usually deserves another pass in the design.

Worked example: checking stopping sight distance

Example

Suppose you are designing a rural two-lane highway with a design speed of 90 km/h on a level grade. Using a perception–reaction time \(t = 2.5\) s and friction coefficient \(f = 0.35\), estimate the minimum stopping sight distance in meters.

First, convert 90 km/h to m/s: \( V = 90 \times \frac{1000}{3600} \approx 25 \,\text{m/s} \). The perception–reaction distance is: \( V t = 25 \times 2.5 = 62.5 \,\text{m} \).

With level grade (\(G = 0\)), the braking distance becomes: \[ \frac{V^2}{2 g (f + G)} = \frac{25^2}{2 \times 9.81 \times 0.35} \approx \frac{625}{6.867} \approx 91 \,\text{m}. \] Adding both components yields: \( SSD \approx 62.5 + 91 \approx 154 \,\text{m} \).

If your crest vertical curve or horizontal curve provides less than about 154 m of sight distance, you would need to adjust the geometry, manage speeds, or add mitigation measures. In practice, design tables in standards round and slightly increase these numbers for conservatism, but doing the calculation yourself builds intuition for how speed, friction, and reaction time interact.

Common pitfalls and engineering checks in highway design

Even when designers use the right equations, several recurring pitfalls show up in design reviews and safety audits. Recognizing them early can save rework and reduce the risk of crashes after opening day.

- Selecting a design speed that is too low for the surrounding network, leading to operating speeds much higher than the design assumptions.

- Misapplying stopping sight distance equations on steep downgrades or confusing passing sight distance with SSD.

- Using curve radii or superelevation values outside the recommended range for climate, speed, or terrain.

- Overlooking sight obstructions from cut slopes, bridge piers, barriers, or vegetation when laying out curves or ramp terminals.

- Ignoring multimodal users (transit, cyclists, pedestrians) on facilities that are classified as highways but function as urban arterials with many access points.

One costly mistake is designing crest vertical curves based solely on comfort criteria (rate of change of grade) and forgetting to check headlight and stopping sight distance for nighttime conditions. A curve that feels smooth in daylight may leave drivers unable to see an object in time at night, especially on high-speed rural facilities.

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical units | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design speed | V | km/h | Drives sight distance, curve radii, and clear zone requirements. |

| Stopping sight distance | SSD | m | Must be available along the driver\u2019s line of sight on tangents and curves. |

| Horizontal curve radius | R | m | Selected based on speed, superelevation, and comfort; larger is generally safer. |

| Maximum grade | Gmax | % | Limited by terrain, climate, and truck performance; steeper grades reduce SSD on upgrades and increase it on downgrades. |

| Lane width | – | m | Common values are 3.3–3.6 m on high-speed facilities; narrower lanes may be acceptable in constrained urban contexts. |

Work with real numbers

Engineering calculators & equation hub

Jump from theory to practice with interactive calculators and equation summaries covering civil, mechanical, electrical, and transportation topics.

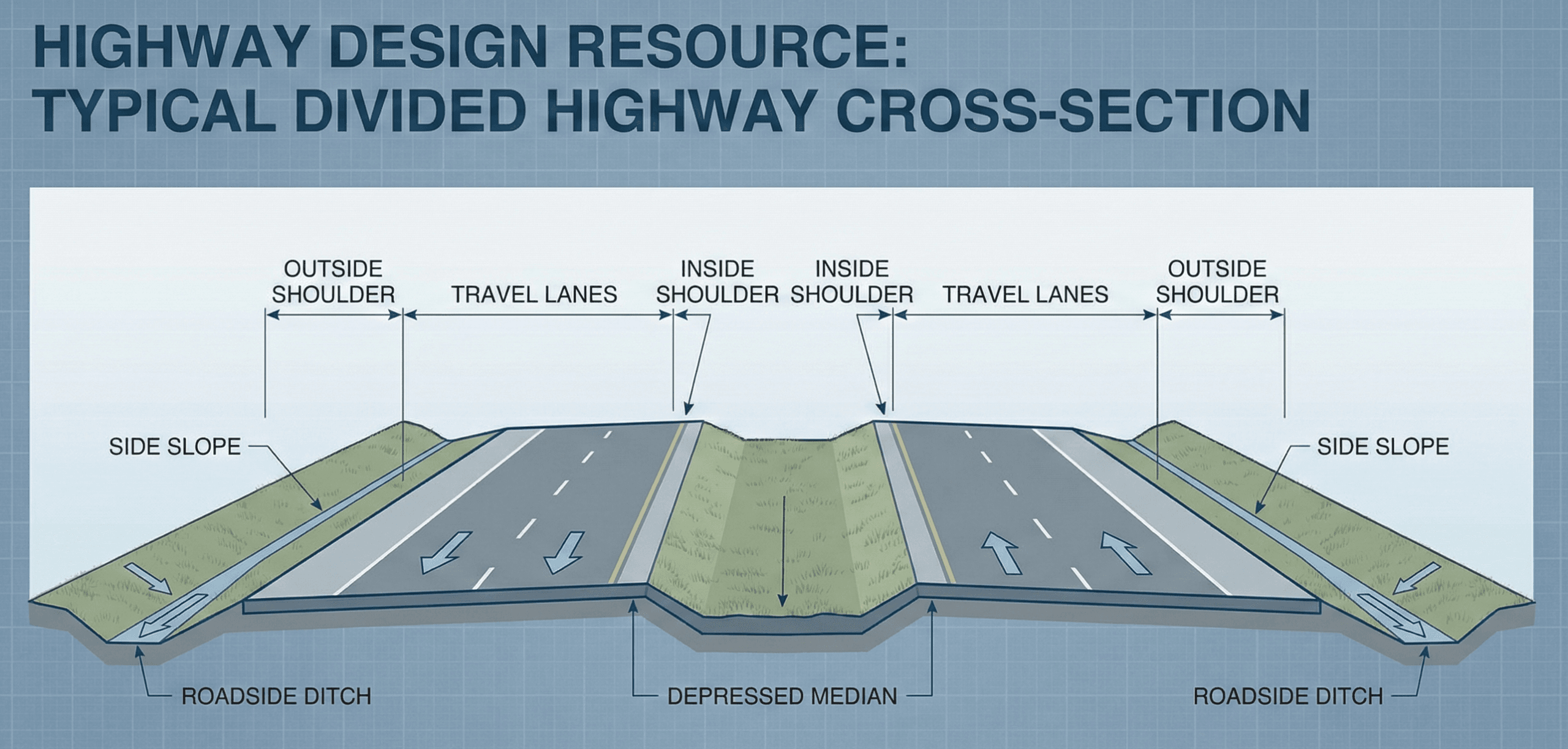

Visualizing a typical highway cross-section

It is often easier to understand highway design by looking at a cross-section slice rather than a plan view. A typical cross-section shows lanes, shoulders, medians, side slopes, ditches, and clear zones all in one view, making it clear how vertical constraints, drainage, and roadside safety interact.

Key standards and design references for highway design

Highway design is heavily standards-driven. While exact requirements vary by country and agency, most practitioners rely on a small set of core references and then supplement them with local design manuals.

- AASHTO Green Book (Geometric Design of Highways and Streets): The primary reference for geometric design in many jurisdictions, covering design speed selection, sight distance, horizontal and vertical alignment, cross-section elements, and roadside design.

- Highway Capacity Manual (HCM): Provides methods for analyzing capacity, level of service, and performance for freeways, multilane highways, arterials, intersections, and interchanges. Traffic and capacity outputs often feed directly into highway design decisions.

- Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) or equivalent: Governs signs, markings, and traffic control devices used in conjunction with the physical roadway so that drivers receive consistent guidance across the network.

- State or national road design manuals: Many transport agencies publish their own geometric design manuals that adapt AASHTO or similar guidance to local conditions, climate, and policy, including region-specific rules for clear zones, barrier use, superelevation, and context-sensitive design.

As a student or early-career engineer, becoming comfortable navigating these documents is just as important as memorizing any single equation. Real design work is about knowing which chapter to open, how to interpret its tables and figures, and how to document your assumptions clearly.

Frequently asked questions

Highway design focuses on the physical layout of the road\u2014its alignment, cross-section, curves, and roadside treatment\u2014while traffic engineering focuses on how vehicles and people move along that road using signals, signs, and operational strategies. In practice, traffic engineers provide volumes, speeds, and turning movements, and highway designers use those inputs to shape a facility that is safe and comfortable to drive. Most successful projects involve tight collaboration between the two disciplines from concept through construction.

You should be comfortable with algebra, trigonometry, and basic calculus, plus the physics of motion and friction. Highway design equations use unit conversions, right-triangle relationships for curves and grades, and parabolic vertical curve formulas. You do not need advanced mathematics to start, but being able to manipulate equations and interpret graphs will make geometric design courses and real projects much easier to follow.

Highway design is central to interstate reconstruction, new bypasses around towns, rural safety improvement projects, urban corridor retrofits, and interchange upgrades. You will use the same principles when adding climbing lanes on steep grades, reconfiguring ramp terminals, designing roundabouts on high-speed approaches, or improving sight distance at rural intersections. Even smaller access projects, like new driveways for major developments, often require geometric design checks to keep the surrounding network safe and efficient.

Summary and next steps

Highway design brings together physics, human behavior, and policy to create roadways that feel natural to drive while quietly meeting strict safety and performance criteria. By understanding design speed, sight distance, horizontal and vertical alignment, and the role of roadside features, you can look at any highway cross-section or plan sheet and see why it was shaped that way. The key equation for stopping sight distance provides a powerful mental model: at higher speeds, drivers need much more time and space, and the geometry must respect that reality.

As you move deeper into transportation engineering, you will see these concepts applied repeatedly in corridors of all sizes, from rural collectors to multilane freeways. The standards you use may change from country to country or agency to agency, but the underlying design philosophy remains remarkably consistent: give drivers a predictable path, sufficient visibility, and a forgiving roadside, and the network will operate more safely and reliably.

To build mastery, practice reading real design plans, tracing alignments through Google Earth, and working through additional design examples. The more cross-sections, profiles, and typical sections you see, the faster you will be able to spot good and bad design decisions in the wild.

Where to go next

Continue your learning path with these transportation engineering resources.

-

Explore the Transportation Engineering hub

See an overview of transportation engineering topics, including traffic flow theory, planning, and safety, with links to more in-depth guides.

-

Learn about Traffic Flow Theory

Understand how flow, speed, and density relate, and how those relationships influence lane counts, control strategies, and design decisions.

-

Read the guide on Transportation Planning

See how long-range planning, demand forecasting, and corridor selection feed into the highway design work covered on this page.

Work with real numbers

Engineering calculators & equation hub

Jump from theory to practice with interactive calculators and equation summaries covering civil, mechanical, electrical, and transportation topics.