Battery Life Calculator

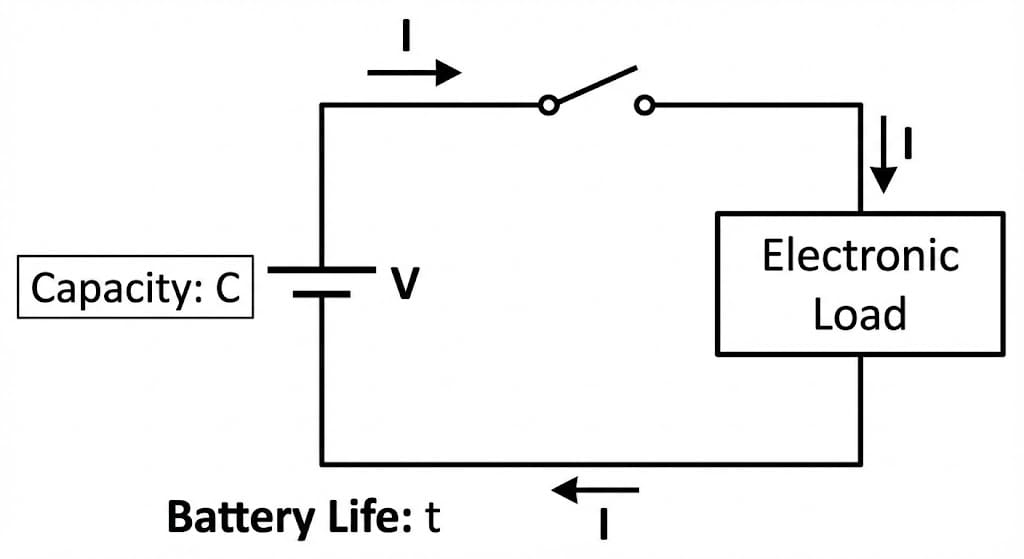

Estimate battery runtime or required capacity using clear electrical variables: capacity C, voltage V, load current I or power P, duty cycle D, and usable fraction η.

Calculation Steps

Topic · Battery Life

Battery Life Calculator – formulas, workflow & real-world examples

This guide explains how battery life is calculated from capacity, voltage, load current or power, duty cycle, and usable capacity, and shows how to use the Battery Life Calculator above to size batteries and estimate runtime for real devices.

How to use the Battery Life Calculator step by step

The Battery Life Calculator above is built to answer two questions engineers ask all the time: “How long will this battery last?” and “How big does my battery need to be?”. It lets you work in either current or power, apply a duty cycle, and include a realistic usable-capacity margin so your design does not die early in the field.

You can run it in two modes: solve for battery life \(t\) from a known battery and load, or solve for required capacity \(C\) given a target runtime. The “Calculation Mode” then decides whether the load is specified as current \(I\) or power \(P\).

-

1

In Solve For, choose either Battery Life t (hours) to estimate runtime, or Required Capacity C (Ah) to size a battery for a desired runtime. The calculator will hide the corresponding input and report that variable in the result box.

-

2

In Calculation Mode, select By Current Draw I if you know the average current in mA or A, or By Power Draw P if your load is specified in watts and you know the battery voltage. The calculator automatically shows the relevant fields (I or P).

-

3

Enter the battery parameters: rated capacity \(C\) (mAh, Ah, or Wh), nominal voltage \(V\), duty cycle \(D_\text{duty}\) (% of time on), and usable capacity / margin \(\eta\) (%). Then enter the load (current or power) using realistic average values.

-

4

Press Calculate (or let the calculator update automatically, depending on the page setup). The result row shows the estimated battery life or required capacity, and the Quick stats table expands with helper metrics like runtime in days, battery energy in Wh, and effective load current.

What battery life really means in engineering terms

At its core, battery life is a simple ratio: how much usable energy the battery can deliver divided by how fast your circuit consumes that energy. The Battery Life Calculator expresses that in hours, but the same idea applies whether you are powering a tiny sensor node or a multi-cell pack in an industrial system.

Manufacturers usually rate batteries in amp-hours (Ah) or milliamp-hours (mAh). For example, a 3000 mAh Li-ion cell can theoretically deliver 3000 mA for one hour, or 300 mA for ten hours, under ideal conditions. In practice, temperature, discharge rate, age, and safety margins reduce that runtime.

To connect capacity to energy, you also need the nominal voltage \(V\). A 3000 mAh, 3.7 V cell has:

Your load then draws either:

- an average current \(I\) (mA or A), or

- an average power \(P\) (W or mW).

If you model the load as a current sink, runtime is proportional to \(C / I\). If you model the load as a power sink, runtime is proportional to \(E / P\). The Battery Life Calculator supports both views so you can match the data sheet or measurement you actually have.

Core battery life formulas & variables used in the calculator

The Battery Life Calculator uses straightforward but flexible formulas so that different unit choices still map to the same physics. The exact path depends on whether you choose current mode or power mode, but the structure is always: usable energy divided by effective load.

Capacity and energy

First, the calculator converts whatever capacity unit you choose into amp-hours and watt-hours:

Duty cycle and effective load

Many devices are not on 100 % of the time. Instead, they wake up, take a measurement or transmit data, then sleep. The calculator models this with a duty cycle \(D_\text{duty}\) in percent:

In current mode, the effective average current is:

In power mode, the effective average power is:

Usable capacity and safety margin

You rarely want to drain a battery to 0 %. You also lose capacity to efficiency, internal resistance, temperature, and aging. The calculator models all of that with a single factor \(\eta\) (% usable capacity):

Battery life and required capacity

Finally, the calculator either solves for runtime \(t\) or for capacity \(C\).

When solving for battery life \(t\) (current mode):

When solving for battery life \(t\) (power mode):

When solving for required capacity \(C\) from a target runtime:

The Battery Life Calculator performs these conversions behind the scenes, and the Quick stats table exposes helper values like effective current and energy so you can cross-check the math.

Duty cycle, usable capacity & why real runtime is shorter

Beginners often take the rated capacity from a data sheet, divide it by load current, and expect that number of hours in the real device. In practice, you almost never get that full ideal runtime. Two of the biggest corrections are duty cycle and usable capacity / efficiency, both of which are explicitly modeled in the Battery Life Calculator.

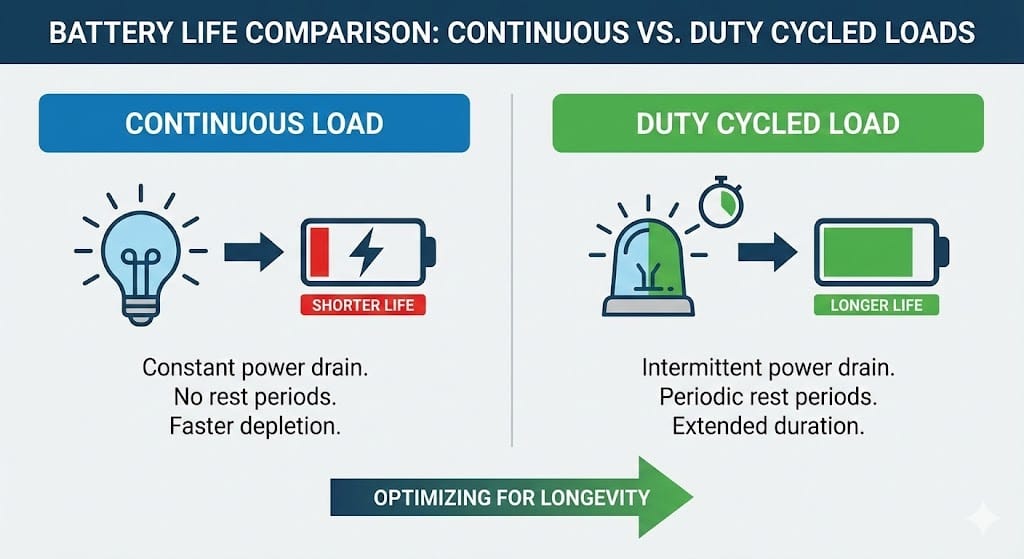

Duty cycle \(D_\text{duty}\) accounts for the fact that many systems sleep most of the time. For example, a sensor that wakes up for 1 s every 10 s has a duty cycle of 10 %. Even if it draws 100 mA while on, the average current over a long period is only 10 mA.

Use this for motors, heaters, or devices that are essentially always on.

IoT nodes, data loggers, and wireless sensors can have duty cycles below 1 %.

Wi-Fi, LTE, or LoRa modules may have short, high-current transmit bursts with long idle periods.

MCUs and displays often draw microamps in sleep and tens of milliamps when active.

The usable capacity factor \(\eta\) then compensates for everything that makes a real battery worse than its headline number. For example:

- Colder temperatures reducing available capacity.

- Voltage cut-off in your regulator or device.

- Internal resistance causing voltage sag at high current.

- Battery aging over years of use or storage.

- Design guard band so the product does not shut off exactly at the spec limit.

A common rule of thumb is to start with \(\eta \approx 70\text{–}85\%\) for consumer gear and a more conservative value for critical systems. In the calculator, simply set the Usable Capacity / Safety Margin \(\eta\) to match how pessimistic you want to be.

When to use current mode vs power mode in the Battery Life Calculator

The Battery Life Calculator offers two practical ways to describe the load: current-based and power-based. Both methods lead to the same answer if the inputs are consistent, so the choice comes down to what information you have.

Current mode – use when you know I

Choose By Current Draw I when the data sheet lists typical current consumption or when you have measured it with an ammeter.

This mode is ideal for microcontrollers, sensors, and analog circuits where current is the natural spec. You specify the unit (mA or A), and the calculator handles all conversions.

Power mode – use when you know P

Choose By Power Draw P when your load is defined by watts, for example for DC–DC converters, LED lighting, or modules specified as “5 W @ 12 V”.

You enter power in W or mW plus the battery voltage. The calculator converts to effective current internally and still exposes energy in the quick-stats table.

Worked battery life examples you can load into the calculator

This section walks through two common scenarios and shows how to plug the numbers into the Battery Life Calculator. For the first example, you can click the Load into Calculator button to pre-fill the fields and view the solution steps above.

Example 1 – 3.7 V Li-ion cell powering a 500 mA load

Suppose you have a single 3.7 V Li-ion cell rated at 3000 mAh. Your device draws 500 mA continuously, and you assume 85 % usable capacity (\(\eta = 85\%\)) with a 100 % duty cycle. How long will the battery last?

Step 1 – convert capacity to Ah and compute usable capacity:

Step 2 – compute effective current (continuous load):

Step 3 – compute battery life:

Result: The calculator will report an estimated battery life of about 5.1 hours, with quick-stats also showing runtime in days (\(\approx 0.21\) days) and battery energy around 9.4 Wh (after applying \(\eta\)).

Example 2 – Low-power sensor with duty-cycled radio

Now consider a battery-powered wireless sensor running from a 2400 mAh AA pack at 3.0 V. The MCU and sensors draw 10 mA when awake for 2 s every minute, and virtually nothing in sleep. The radio bursts at 60 mA for 0.5 s during that 2 s window. Over many minutes, the effective duty cycle for the active period is:

The average current during the 2 s window is roughly \((10~\text{mA} \cdot 1.5~\text{s} + 60~\text{mA} \cdot 0.5~\text{s})/2~\text{s} = 22.5~\text{mA}\). Multiplying by the duty cycle gives:

With \(\eta = 80\%\), the usable capacity is \(C_\text{usable} = 2400~\text{mAh} \cdot 0.8 = 1920~\text{mAh} = 1.92~\text{Ah}\). The estimated battery life becomes:

Result: The sensor can run for on the order of 3–4 months on a fresh pack, depending on temperature and aging. In the Battery Life Calculator, you would enter \(C = 2400~\text{mAh}\), \(I = 0.75~\text{mA}\), \(D_\text{duty} = 100\%\) (since the 0.75 mA is already averaged) and \(\eta = 80\%\).

Design tips, safety margins & common battery life pitfalls

Even with a good calculator, it is easy to over-estimate battery life. This section highlights practical tips to make your estimates more robust and your designs more reliable.

- Use realistic average current or power. Measure the actual device profile with an ammeter or power analyzer instead of guessing from data sheet “typical” numbers.

- Include worst-case duty cycle. Assume the device may transmit more often, stay awake longer, or run extra computations under heavy use.

- Derate capacity for temperature. Cold environments can significantly reduce usable capacity, especially for certain chemistries.

- Consider battery aging. If your product must last years in the field, reduce \(\eta\) to account for loss of capacity over time.

- Watch regulator cut-off voltage. Your system may shut down while the battery still appears to have some capacity left, especially with buck or boost converters.

- Check C-rate limits. High discharge currents raise internal losses and reduce effective capacity; for high-power loads, consider larger packs or different chemistries.

The Battery Life Calculator helps here by letting you quickly try different “what-if” scenarios: increase duty cycle, lower usable capacity, or change the load, and see how the runtime moves. The quick-stats panel makes it easier to communicate results to teammates (for example, “Our design runs about 3 days at 100 % duty, 10 days at 30 % duty.”).

Battery Life & Battery Life Calculator – frequently asked questions

How do I calculate battery life from mAh and mA?

Convert capacity to amp-hours and divide by the effective load current. If your battery is \(C_\text{mAh}\) and your average current is \(I_\text{mA}\), a quick ideal estimate is:

In the Battery Life Calculator, you can refine this by adding duty cycle and usable capacity \(\eta\). Set \(C\) in mAh, choose current mode, enter \(I\), and optionally adjust duty cycle and \(\eta\) to get a more realistic runtime.

How do I use the Battery Life Calculator to size a battery for a target runtime?

In Solve For, choose Required Capacity C (Ah), then enter your target runtime \(t\) in hours. Fill in the load (current or power), duty cycle, and desired usable capacity \(\eta\). The calculator will output the required capacity in amp-hours, which you can convert to mAh or Wh as needed when picking a specific cell or pack.

What duty cycle should I enter for devices that sleep most of the time?

If you already know the average current over a long time window, you can set duty cycle to 100 % and simply use that average current. If you only know the active current and active time, compute:

Then either let the calculator apply that duty cycle, or compute the averaged current yourself and enter it with duty cycle set to 100 %.

Why is the real battery life shorter than what the calculator predicts?

Any battery life calculation depends heavily on assumptions. If your real runtime is shorter, common causes include: colder temperatures, higher actual duty cycle, higher peak currents causing voltage sag, battery aging, or an optimistic usable capacity \(\eta\). Try lowering \(\eta\), increasing duty cycle, or using measured current waveforms to align the calculator with your real system.

Can I use the Battery Life Calculator for multi-cell packs and series/parallel configurations?

Yes. For series packs, capacity in Ah stays the same while voltage increases, so enter the pack voltage and capacity of one string. For parallel packs, capacity increases while voltage stays the same, so enter the summed capacity and nominal voltage. As long as you use the correct pack-level capacity and voltage, the Battery Life Calculator will give a valid energy-based runtime estimate.

How should I choose the usable capacity / safety margin percentage?

There is no single right value, but common practice is: 70–80 % for consumer devices, 60–70 % for long-life remote systems, and even lower for safety-critical applications. Start with 80–85 % for rough estimates, then tighten the margin once you have real test data on how your battery behaves under your specific load profile and temperature range.