Thermodynamics · Heat Capacity Equation

Heat Capacity Equation – relating heat, temperature change & material properties

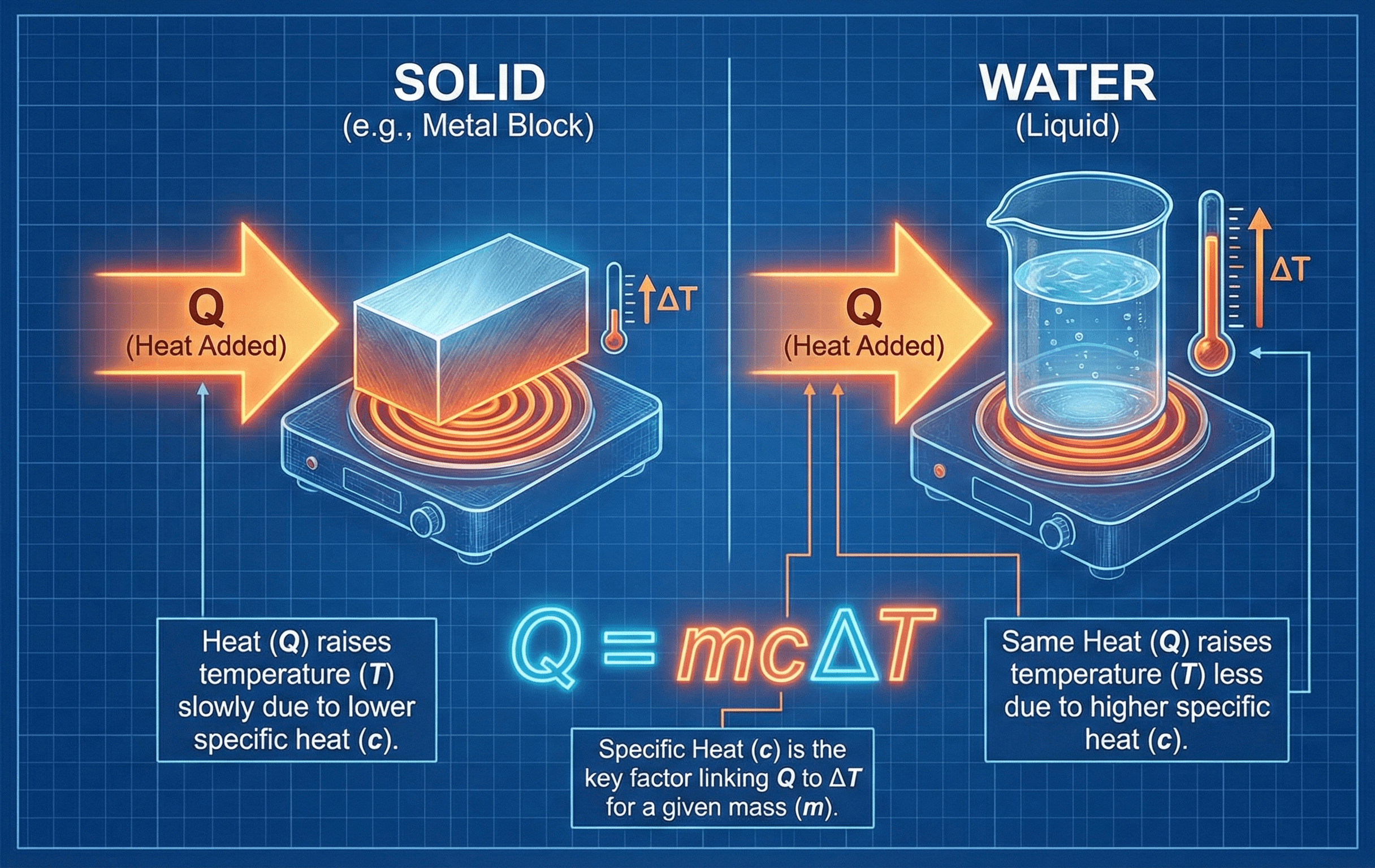

The heat capacity equation connects the amount of heat added or removed from a system to its temperature change and material properties, giving you a direct way to size heaters, coolers, and thermal storage in real engineering problems.

Quick answer: what the heat capacity equation tells you

Core formulas

The heat capacity equation says that the heat added or removed from a system is proportional to its heat capacity (or specific heat capacity), its mass, and the temperature change: if you know any three of \(Q\), \(m\), \(c\), and \(\Delta T\), you can solve for the fourth.

In everyday engineering, the heat capacity equation is your first stop when sizing thermal systems. You combine it with power and time relationships (\( Q = P t \)) to see whether a given heater, heat exchanger, or thermal store can deliver the required temperature change within a desired time window. The most common working form is \( Q = m c \Delta T \), where \(c\) is the specific heat capacity of the material.

Because the equation is linear in both mass and temperature change, doubling the mass or the required \(\Delta T\) doubles the required heat input. This simple proportionality makes it easy to scale examples from the lab to full-size systems. The main subtlety lies in picking the correct \(c\) value (solid vs liquid, constant-pressure vs constant-volume, temperature range, mixture composition) and in being careful with units.

In the sections below, we’ll define each symbol precisely, walk through how to use the equation step by step, and then apply it to realistic design-style problems in the worked examples section.

Symbols, units & notation in the heat capacity equation

The heat capacity equation is usually written in one of two closely related forms. In “lumped” form, you work with an overall heat capacity \(C\) for the whole object: \( Q = C \Delta T \). In material-property form, you write \( Q = m c \Delta T \), where the specific heat capacity \(c\) is tabulated for different materials. The table below summarizes the most common symbols and engineering units.

Common notation & base units

| Symbol | Quantity | Typical SI unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( Q \) | Heat (thermal energy) | Joule (J) or kJ | Total heat added to or removed from the system. Positive \(Q\) is usually taken as heat added; negative \(Q\) as heat removed. |

| \( C \) | Heat capacity | J/K | Overall ability of an object or system to store heat. Relates heat to temperature change via \( C = Q / \Delta T \) for that whole body. |

| \( c \) | Specific heat capacity | J/(kg·K) | Heat capacity per unit mass. Relates heat to mass and temperature change through \( Q = m c \Delta T \). Sometimes written as \(c_p\) or \(c_v\). |

| \( c_p \) | Specific heat at constant pressure | J/(kg·K) | Specific heat capacity measured or applied at constant pressure (most common for liquids and gases in HVAC, process, and power calculations). |

| \( c_v \) | Specific heat at constant volume | J/(kg·K) | Specific heat capacity at constant volume, often used in ideal-gas and internal energy relations for closed systems. |

| \( m \) | Mass | kg | Mass of the body or fluid experiencing the temperature change. For mixtures, \(m\) can be the mass of a single component or the total mass depending on context. |

| \( \Delta T \) | Temperature change | K or °C | Final minus initial temperature: \( \Delta T = T_2 – T_1 \). A change of 1 K equals a change of 1 °C, so increments are interchangeable in most engineering work. |

Unit systems & practical notes

- In SI, pair Joules (J), kilograms (kg), and Kelvin or degrees Celsius for temperature differences. This keeps \( Q = m c \Delta T \) dimensionally clean.

- In U.S. customary units, the analogous equation uses Btu, lbm, and °F with specific heat often given in Btu/(lbm·°F). Be careful not to mix SI and U.S. units in the same calculation.

- For temperature differences only, \(\Delta T\) in K and °C are numerically identical; you do not add 273.15 to a temperature difference.

- Many tables give \(c_p\) and \(c_v\) that vary with temperature; using a single “average” value over a broad range introduces error you should account for in your safety margins.

Once your symbols and units are clear, you can plug numbers into the heat capacity equation by hand or use a dedicated Heat Capacity Calculator to iterate quickly on different materials, masses, and temperature targets.

How the heat capacity equation links energy and temperature

At its core, the heat capacity equation states that temperature change is a consequence of energy input divided by how “thermally inert” the system is. A large heat capacity means you can add a lot of heat with only a small rise in temperature; a small heat capacity means even modest heating causes large temperature swings.

For a single, uniform material, the most useful working form is:

This is the version you’ll use in most hands-on calculations and in the worked examples later on. It assumes that the specific heat capacity is approximately constant over the temperature range of interest and that temperature is uniform within the body (a “lumped” capacitance assumption).

Step-by-step: using \( Q = m c \Delta T \) in practice

When someone asks “How much heat is required to heat this fluid?” or “What will the final temperature be after a certain heat input?”, they’re really asking you to apply this equation. A typical workflow looks like:

- Identify the system (for example, a tank of water, an aluminum block) and isolate the mass \(m\) that will change temperature.

- Choose an appropriate value of \(c\) from a reliable table at a representative temperature and state (solid, liquid, gas).

- Compute the temperature change \(\Delta T = T_2 – T_1\) based on the required or resulting conditions.

- Apply \( Q = m c \Delta T \) and solve for the unknown: \(Q\), \(m\), \(c\), or \(\Delta T\).

- Check that the result’s units and magnitude are physically reasonable before using it in design decisions.

In design sizing, you often then relate \(Q\) to heater or chiller power using \( Q = P t \) (with \(P\) in watts and \(t\) in seconds) to decide whether the available equipment can achieve the temperature change in the available timeframe.

Overall heat capacity \(C\) vs. specific heat capacity \(c\)

For complex objects, you may not want to track individual materials. Instead, you can treat the entire system as having a single effective heat capacity \(C\). In that case, you work with:

where \(C\) has units of J/K. If the system is made of a single material, then \( C = m c \). For composite systems (for example, water plus tank walls plus internal components), you can build an effective \(C\) by summing the individual contributions:

This approach is especially useful in controls and lumped-capacitance models, where you want a simple first-order relationship between heat input and temperature response without resolving every detail of the geometry.

Dimensional checks & typical magnitudes

A quick dimensional check helps catch algebra and unit mistakes. In SI, the dimensions of \( Q = m c \Delta T \) are:

Typical specific heat capacities at room temperature give you an intuition benchmark: water is about \(4.18~\text{kJ/(kg·K)}\), many oils are in the \(1.5\text{–}2.5~\text{kJ/(kg·K)}\) range, and common metals are much lower (for example, steel is roughly \(0.45~\text{kJ/(kg·K)}\)). If your calculation says a small mass of metal needs more heat than the same mass of water for the same \(\Delta T\), something is probably off.

Worked examples using the heat capacity equation

The questions people ask most often about the heat capacity equation are practical: “How much energy does my heater need?”, “What final temperature will I reach after a given heating time?”, or “What is the specific heat of this material from my lab data?”. The examples below mirror those real-world tasks and show how to move from word problem to numbers.

Example 1 – Heat required to raise water temperature

A small hot-water tank contains \( 80~\text{L} \) of water at \( 20^\circ\text{C} \). You want to raise the water to \( 60^\circ\text{C} \) for domestic use. Assuming the density of water is \( 1{,}000~\text{kg/m}^3 \) and its specific heat capacity is \( c = 4.18~\text{kJ/(kg·K)} \), how much heat energy is required?

- Convert the volume of water to mass.

- Compute the temperature change \(\Delta T\).

- Apply \( Q = m c \Delta T \) using consistent units.

Result: You need roughly \(13.4~\text{MJ}\) of heat to raise the 80 L of water from \(20^\circ\text{C}\) to \(60^\circ\text{C}\). In design, you would pair this with heater power to estimate warm-up time: for example, a 6 kW heater could supply this heat in about \(13{,}376~\text{kJ} / 6~\text{kJ/s} \approx 2{,}230~\text{s}\), or roughly 37 minutes (ignoring losses).

Example 2 – Final temperature after heating a metal block

An aluminum block with mass \( m = 2.5~\text{kg} \) is initially at \( 25^\circ\text{C} \). A lab heater supplies \( Q = 90~\text{kJ} \) of heat to the block while it is thermally isolated from the surroundings. Take the specific heat capacity of aluminum as \( c = 900~\text{J/(kg·K)} \). What is the final temperature of the block?

- Convert all quantities to base SI units (J, kg, K).

- Rearrange \( Q = m c \Delta T \) to solve for \(\Delta T\).

- Add \(\Delta T\) to the initial temperature to find the final temperature.

Result: The aluminum block warms from \(25^\circ\text{C}\) to \(65^\circ\text{C}\). This example highlights how metals with relatively low specific heat capacities heat up quickly compared to water for the same energy input.

Example 3 – Back-calculating specific heat from calorimetry data

In a simple calorimetry experiment, a \( 0.40~\text{kg} \) sample of an unknown solid at \( 150^\circ\text{C} \) is dropped into \( 0.80~\text{kg} \) of water initially at \( 20^\circ\text{C} \) inside an insulated container. After stirring, the final equilibrium temperature is \( 30^\circ\text{C} \). Assuming no heat loss and taking the specific heat capacity of water as \( c_{\text{water}} = 4{,}180~\text{J/(kg·K)} \), find the solid’s specific heat capacity.

- Write an energy balance: heat lost by the solid equals heat gained by the water.

- Express each heat term using \( Q = m c \Delta T \).

- Solve the resulting equation for the unknown specific heat \(c_{\text{solid}}\).

Result: The unknown solid has a specific heat capacity of about \(700~\text{J/(kg·K)}\), comparable to some common metals and ceramics. This is exactly the sort of “find \(c\) from experimental data” problem where the heat capacity equation is the main workhorse.

Design tips, limitations & checks when using the heat capacity equation

In design, the heat capacity equation is just one piece of the puzzle. Real systems have heat losses, non-uniform temperatures, phase changes, and temperature-dependent properties. Still, a clean first-pass \( Q = m c \Delta T \) calculation gives you an essential sanity check: it tells you whether your heater or cooler is even in the right ballpark before you invest time in detailed simulations.

The first choice is which “flavor” of heat capacity to use for the problem at hand.

- For a solid block or a well-mixed liquid volume, \( Q = m c \Delta T \) with tabulated \(c\) is usually the most straightforward.

- For gases in open systems (ducts, HVAC coils, compressors), \( c_p \) is typically the correct property to use, since pressure is roughly constant.

- For closed, fixed-volume gas systems, \( c_v \) is more appropriate when relating heat to temperature change at constant volume.

- For composite systems or control models, an overall heat capacity \(C_{\text{total}} = \sum m_i c_i\) gives a useful lumped parameter.

- Mixing temperature levels and temperature differences (for example, adding 273.15 to \(\Delta T\) or using Kelvin for one term and Celsius for another inconsistently).

- Ignoring heat losses to the environment, especially when warm-up times seem “too optimistic” compared to real systems.

- Using a single constant \(c\) over a huge temperature range where the property changes significantly (for example, near boiling or phase change regions).

- Applying \( Q = m c \Delta T \) through a phase change without adding latent heat terms, which can dominate the energy budget.

Before finalizing a design based on the heat capacity equation, a few quick checks can keep you out of trouble.

- Compare your required \(Q\) and heater power \(P\) to see if the warm-up or cool-down time is realistic for the application.

- Check that predicted temperatures stay comfortably within material and fluid limits, with adequate safety factors for degradation or boiling.

- Ask whether thermal stratification, poor mixing, or large Biot numbers might invalidate the “lumped temperature” assumption, signaling the need for more detailed modeling.

Heat capacity equation – FAQ

What is the heat capacity equation in simple terms?

In simple terms, the heat capacity equation says that the heat required to change a material’s temperature is proportional to how much material you have, the material’s ability to store heat, and how big a temperature change you want. Written as \( Q = m c \Delta T \), it tells you that doubling the mass or the required temperature rise doubles the heat needed, assuming the specific heat \(c\) stays the same.

How do I calculate heat required using the heat capacity equation?

To calculate the required heat, identify the mass \(m\) of the material, pick an appropriate specific heat capacity \(c\) from a reliable table, and compute the temperature change \(\Delta T = T_2 – T_1\). Then plug into \( Q = m c \Delta T \). Make sure all units are consistent (for example, kg, J/(kg·K), and K) so that \(Q\) comes out in Joules. If you know heater power \(P\), you can estimate heating time from \( t = Q / P \).

What is the difference between heat capacity and specific heat capacity?

Heat capacity \(C\) is an extensive property of a whole object or system and has units of J/K; it tells you how much heat is needed to raise that specific system by 1 K. Specific heat capacity \(c\) is an intensive material property with units of J/(kg·K) that tells you how much heat is needed per kilogram for a 1 K rise. They are related by \( C = m c \). In many design calculations, you work directly with \(c\) and the mass, but overall system models often use a single lumped \(C\).

Should I use \(c_p\) or \(c_v\) in my calculations?

For most liquids and solids, \(c_p\) and \(c_v\) are very similar, so basic heating and cooling calculations can safely use tabulated “specific heat” values without worrying about the distinction. For gases, however, the difference matters. Use \(c_p\) for processes at roughly constant pressure (such as flow through heat exchangers and ducts) and \(c_v\) for constant-volume or internal-energy-focused calculations in closed systems. When in doubt, check how the property was defined in your data source and match it to the physical situation.

References & further reading

- Standard thermodynamics and heat transfer textbooks covering specific heat, heat capacity, and energy balances for engineering systems.

- Property tables and charts from reputable handbooks and data compilations providing temperature-dependent specific heat values for common engineering materials.

- Application notes from heater, chiller, and heat exchanger manufacturers that walk through sizing examples using \( Q = m c \Delta T \) and related relationships.