Electrical Engineering · Kirkoff’s Voltage Law

Kirkoff’s Voltage Law – loop voltages, drops & energy conservation in circuits

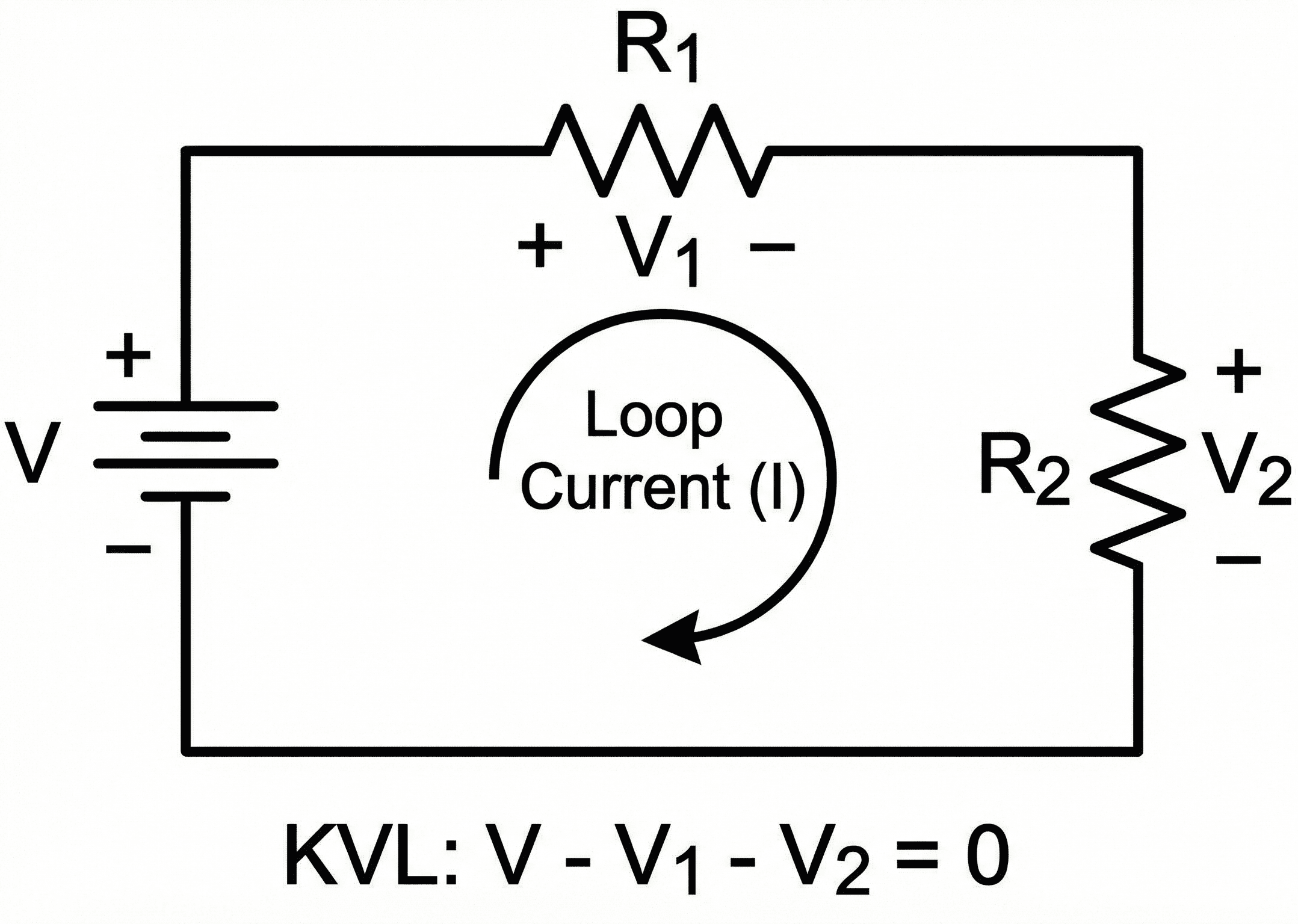

Kirkoff’s Voltage Law (properly Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law, KVL) states that the algebraic sum of all voltage rises and drops around any closed loop in a circuit is zero, capturing energy conservation in lumped electrical networks.

Quick answer: what Kirkoff’s Voltage Law (KVL) tells you

Core loop equation

Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law (often misspelled as Kirkoff’s Voltage Law) says that if you start at any point in a circuit and walk around a closed loop, adding voltage rises and subtracting voltage drops with signs, you must end up back at zero.

Conceptually, KVL is just energy conservation written in voltage form. Voltage is energy per unit charge, so when a test charge goes around a closed loop, the total energy gained from sources must equal the energy lost in loads and resistive drops. If you treat voltage rises (for example, going from the negative to the positive terminal of a source) as positive and voltage drops (for example, across a resistor in the direction of current) as negative, the signed sum must be zero.

In practice, you pick a loop direction, assign polarities, and write an equation like \( +V_{\text{source}} – V_{R1} – V_{R2} – \cdots = 0 \). Combined with Ohm’s Law and device models, those loop equations let you solve for unknown currents, drops, and sometimes even missing source values. KVL is one of the two core “Kirchhoff laws” you use constantly in circuit analysis, alongside Kirchhoff’s Current Law (KCL) at nodes.

Symbols, loop notation & units in Kirkoff’s Voltage Law

Mathematically, Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law is usually written as \( \sum_{k=1}^{n} v_k = 0 \) around a closed loop. In many textbooks and circuit analysis courses, you’ll also see forms like \( \sum \text{rises} = \sum \text{drops} \) or \( V_{\text{source,total}} = \sum \text{load drops} \). The table below summarizes common symbols and how they’re used with KVL.

Common KVL notation & quantities

| Symbol | Quantity | Typical unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( v_k \) | Element voltage | Volt (V) | Signed voltage across the \(k\)-th element in the loop. Positive or negative depending on your loop direction and chosen polarity. |

| \( \sum_{k=1}^{n} v_k \) | Loop sum | Volt (V) | Algebraic sum of all element voltages around a closed loop. KVL states that this sum is zero for valid lumped circuits. |

| \( V_{\text{s}} \) | Source voltage | Volt (V) | Applied source or supply voltage (battery, DC supply, AC source). Often treated as a voltage rise in the loop direction. |

| \( V_R \) | Resistor drop | Volt (V) | Voltage drop across a resistor, commonly modeled using Ohm’s Law \( V_R = I R \). Treated as a voltage drop in the direction of current. |

| \( I \) | Loop current | Ampere (A) | Assumed current circulating around a loop. In simple series circuits, the same current flows through every element in the loop. |

| \( \oint \vec{E} \cdot d\vec{\ell} \) | Field line integral | Volt (V) | Continuous version of KVL from electromagnetics: line integral of electric field around a closed path. Zero for electrostatic fields (no time-varying magnetic flux). |

Unit systems, signs & phasors

- SI units: voltage in volts (V), current in amperes (A), resistance in ohms (Ω). KVL itself is unit-agnostic as long as all voltages share the same unit.

- Sign conventions: pick a loop direction (clockwise or counter-clockwise) and stick to it. Treat going from − to + across a source in the loop direction as a rise and across a passive element in the direction of current as a drop.

- AC analysis: in sinusoidal steady-state, KVL applies to complex phasor voltages. The loop sum of phasor voltages is still zero; you just keep track of magnitudes and phase angles.

In installation design, KVL is what tells you how much voltage you lose along long feeders and branch circuits. Once you know the allowable voltage drop and loop currents, you can size conductors appropriately with tools like the Cable Sizing Calculator to keep loads within their required voltage range.

How Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law comes from energy conservation

At its core, KVL is a statement about energy per unit charge. Imagine a test charge making a complete lap around a closed loop. As it passes through sources, it may gain energy; as it passes through resistors and loads, it loses energy as heat, light, motion, or some other form. By the time it returns to the starting point, the net change in energy must be zero. Divide by the charge and you get the KVL statement that the sum of voltage changes is zero.

From electric field to lumped-circuit KVL

In continuous form, the electric field \( \vec{E} \) around a closed loop obeys

for electrostatic conditions (no time-varying magnetic flux linking the loop). When you partition the loop into discrete elements and define each element voltage as \( v_k = -\int_{\ell_k} \vec{E} \cdot d\vec{\ell} \), the line integral over the whole closed path becomes the sum of the individual element voltages. The continuous equation above therefore turns into the discrete KVL form

This is why KVL works so well in lumped circuits: we assume that voltage drops are localized across components and that fields are “confined” inside them, so the circuit graph captures the essential energy story.

Loop direction, polarities & algebraic signs

In real calculations, the trickiest part of KVL is sign conventions. A robust procedure is:

- Draw the circuit schematically and pick a loop direction (clockwise is a common choice, but either is fine).

- Label polarities on element voltages, usually following the passive sign convention (current enters the positive-labeled terminal of passive elements).

- Walk around the loop in your chosen direction. When you go from − to + across an element, add its voltage; when you go from + to −, subtract it.

If you make a sign mistake, the math will often “fix” it by returning a negative current or voltage value, indicating that your assumed direction is opposite to the actual one. The law itself does not fail; the algebra just encodes your initial assumptions and their consequences.

KVL and KCL work together. KVL constrains voltages around loops, while KCL constrains currents at nodes. In systematic methods like mesh analysis and nodal analysis, you use KVL-based loop equations or KCL-based node equations to build solvable linear systems for complex circuits with many unknowns.

Worked KVL examples for real circuits

The value of Kirkoff’s Voltage Law becomes clear when you use it on actual circuits. The examples below walk through single-loop and multi-loop scenarios, including one that connects directly to voltage-drop constraints on long cable runs. You can adapt the same patterns to much larger networks.

Example 1 – Single loop with series resistors

A 12 V DC supply feeds three series resistors: \(R_1 = 100~\Omega\), \(R_2 = 220~\Omega\), and \(R_3 = 330~\Omega\). Find the current in the loop and the voltage drop across each resistor. Verify your result with KVL.

- Compute the equivalent series resistance \(R_{\text{eq}}\).

- Use Ohm’s Law with the supply voltage to find the loop current.

- Compute each drop \(V_{Ri} = I R_i\) and check that their sum equals the source voltage.

Check KVL around the loop (taking the source as a rise and resistor drops as negatives):

Result: The loop current is about \(18.5~\text{mA}\), and the three voltage drops are approximately 1.85 V, 4.06 V, and 6.09 V. Their algebraic sum with the 12 V source returns zero, as KVL requires.

Example 2 – Two sources in one loop

Consider a loop with two DC sources and two resistors: a 24 V source, a 9 V source (opposing the 24 V), \(R_1 = 150~\Omega\), and \(R_2 = 270~\Omega\) in series. Assume clockwise loop current \(I\). Find \(I\) using KVL.

- Choose a loop direction (clockwise) and mark polarities consistent with that direction.

- Write a single KVL equation around the loop, treating the 24 V source as a rise and the 9 V source as a drop (since it opposes).

- Solve for \(I\), then interpret the sign of the result.

Result: The loop current is about \(35.7~\text{mA}\) in the assumed clockwise direction. Plugging back into KVL shows that the 24 V source “wins” over the opposing 9 V source, with the remainder dropping across the series resistance.

Example 3 – Voltage drop along a feeder to a load

A 120 V single-phase circuit feeds a 10 A load via a long copper cable with total loop resistance (out and back) of \(0.8~\Omega\). What is the voltage at the load terminals, and what fraction of the source voltage is lost in the cable? Assume steady-state DC behavior so KVL applies in the usual lumped sense.

- Model the circuit as a source, series cable resistance, and load resistance in one loop.

- Use Ohm’s Law to find the cable voltage drop \(V_{\text{cable}} = I R_{\text{cable}}\).

- Apply KVL to compute the load voltage and express the drop as a percentage.

Result: The load sees about 112 V, meaning roughly 6.7% of the source voltage is lost in the cable. Many wiring standards limit branch-circuit voltage drop to around 3–5%, so a KVL-based drop check like this is a key first step before formally sizing the cable.

Design tips, limits & sanity checks for KVL

In everyday use, Kirkoff’s Voltage Law feels almost trivial: “of course the voltages must add up.” But in real circuits and design work, there are important assumptions hiding behind that simplicity. Being explicit about them helps you apply KVL safely and spot cases where deeper models are needed.

The standard lumped-circuit KVL model assumes that wavelengths are long compared to circuit dimensions and that fields are mostly confined to components. Under those conditions, you can safely use KVL in:

- Low-frequency DC and AC power circuits (mains, industrial control panels, basic power supplies).

- Electronics where trace lengths are short relative to signal wavelength (most low-speed analog and digital boards).

- Feeder and branch circuits where you care about total voltage drop rather than distributed field effects.

- Mixing sign conventions – for example, treating a source as a rise in one part of the loop and as a drop in another, or reversing resistor polarities relative to current direction.

- Forgetting elements – leaving out contact resistance, cable resistance, or small drops across protection devices when they actually matter for tight voltage budgets.

- Writing more independent KVL equations than the circuit can support, leading to redundant equations and confusion when setting up simultaneous solutions.

KVL is not “wrong” in advanced cases, but the simple lumped form \( \sum v_k = 0 \) no longer captures all effects. Watch out for:

- High-frequency or RF circuits: when line lengths are comparable to a signal’s wavelength, you must model transmission-line behavior and distributed parameters, not just lumped voltage drops.

- Loops with time-varying magnetic flux: if a changing magnetic field links your loop (for example, in transformer cores or large inductive structures), Faraday’s Law adds an induced emf term. The simple “sum of element voltages equals zero” becomes “sum of element voltages equals the negative rate of change of linked flux.”

- Non-ideal references and grounds: long or resistive ground paths can carry significant current, so “ground” nodes are not at the same potential everywhere. KVL still applies, but your circuit model must include those impedances explicitly.

As long as you are aware of these limits, KVL remains one of the most powerful quick-check tools in electrical engineering. Anytime a set of measured voltages around a loop does not add up (within measurement uncertainty), it is a strong hint of wiring errors, failing components, or incorrect assumptions about the circuit topology.

Kirkoff’s Voltage Law – FAQ

What is Kirkoff’s Voltage Law in simple terms?

In plain language, Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law says that if you start at one point in a circuit and go all the way around a closed loop, the total “ups” in voltage must equal the total “downs.” Sources give energy to charges (voltage rises), and loads take it away (voltage drops), so by the time you return to where you started the net change is zero. Mathematically, that is written as \( \sum v_k = 0 \) around any closed loop.

How do you apply KVL step by step?

The standard workflow is:

- Draw a clear circuit diagram and label all known voltages, currents, and components.

- Choose a loop (or set of loops) and assign a direction for each loop current.

- Mark polarities on element voltages consistent with your loop directions and current assumptions.

- Walk around each loop, adding voltage rises and subtracting drops to write a KVL equation that equals zero.

- Combine those equations with Ohm’s Law and device relationships, then solve the resulting system for the unknowns.

If a calculated current comes out negative, it simply means the actual current direction is opposite to what you assumed; KVL itself is still satisfied.

When does Kirkoff’s Voltage Law not strictly hold?

The lumped-circuit form of KVL assumes that electric and magnetic fields are quasi-static and that no significant time-varying magnetic flux links the loop. At very high frequencies, in RF circuits, or in situations where a loop encloses changing magnetic flux (like around transformer windings), a more general form of Faraday’s Law applies, and you must include induced emf terms. In those cases, a simple sum of component voltages set to zero no longer captures all the physics, even though underlying energy conservation still holds.

Is KVL the same as conservation of energy?

KVL is a direct consequence of conservation of energy, but expressed in voltage terms for lumped circuits. It says that the net change in energy per unit charge around a closed path is zero, which is a specific application of the broader conservation law. However, conservation of energy is more general – it applies even when simple circuit models break down, while KVL in its basic form assumes a valid lumped circuit representation and negligible radiation or distributed effects.

References & further reading

- Standard introductory circuit analysis textbooks, which derive Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law from Maxwell’s equations and show its use in mesh analysis and network theorems.

- Power systems and wiring design handbooks that discuss voltage drop limits, feeder and branch-circuit design, and how KVL underpins allowable voltage variation at loads.

- University lecture notes on basic circuit theory and electromagnetics, especially sections connecting the line integral of electric field to discrete circuit equations like KVL and KCL.