Engineering Mathematics · Pythagorean Theorem

Pythagorean Theorem – right triangles, distance & engineering layouts explained

The Pythagorean Theorem links the two perpendicular legs of a right triangle to its diagonal, giving engineers a simple but powerful way to compute distances, diagonals, clearances, and resultants in 2D layouts and design checks.

Quick answer: what the Pythagorean Theorem tells you

Core formula for a right triangle

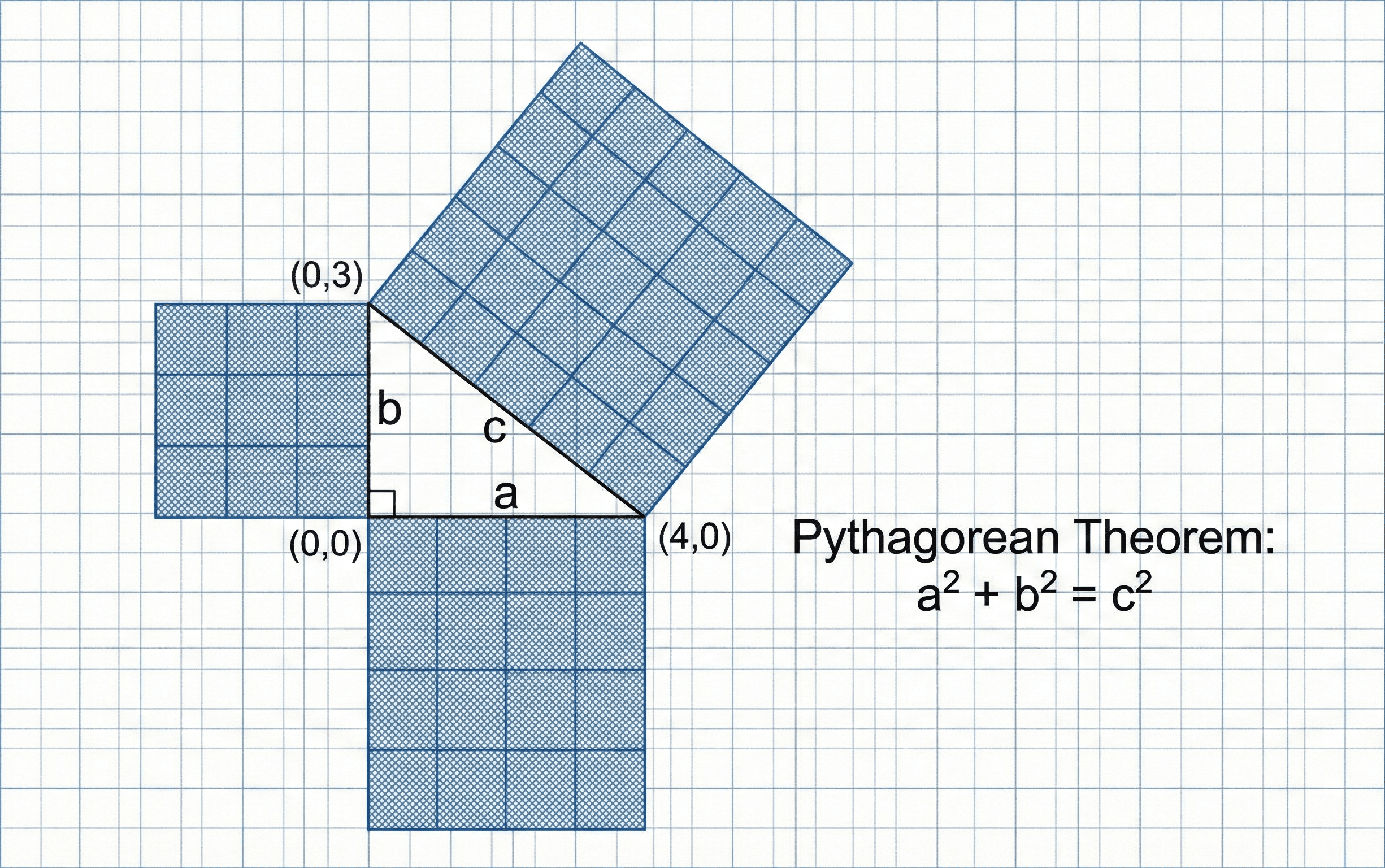

The Pythagorean Theorem states that in a right triangle, the square of the hypotenuse \(c\) equals the sum of the squares of the two perpendicular legs \(a\) and \(b\); this lets you turn a pair of perpendicular offsets into a single diagonal distance.

In practice, engineers rarely think about “triangles” in isolation. Instead, they draw a plan, mark perpendicular offsets, and then need the distance between two points, the diagonal length of a panel, or the magnitude of a resultant load. The Pythagorean Theorem is the shortcut that turns those perpendicular dimensions into a single length using \( c = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2} \).

The same idea underlies the 2D distance formula in coordinate geometry and the way you compute magnitudes of rectangular vectors. Whenever two directions are perpendicular and you know the components along each axis, you can safely combine them using the Pythagorean relationship. As the worked examples show, this crops up everywhere from estimating cable lengths to checking that a foundation is built square.

Symbols, units & notation in the Pythagorean Theorem

The Pythagorean relationship is usually written as \( a^2 + b^2 = c^2 \), where \(a\) and \(b\) are the lengths of the legs forming the right angle and \(c\) is the hypotenuse. In coordinate form, the same idea appears as the distance formula between two points in a plane:

Whatever notation you use, the rule of thumb is simple: all lengths must be in the same units, and the theorem applies only when the angle between the legs is exactly 90°. The table below summarizes common symbols, units, and interpretations you will see in engineering contexts.

Common notation for right triangles & distances

| Symbol | Quantity | Typical units | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( a \) | Leg 1 (adjacent side) | m, mm, ft, in | One of the perpendicular sides forming the right angle; often called the “run,” “width,” or “x-offset” depending on the drawing. |

| \( b \) | Leg 2 (opposite side) | m, mm, ft, in | The other perpendicular side; often referred to as the “rise,” “height,” or “y-offset.” |

| \( c \) | Hypotenuse | m, mm, ft, in | Side opposite the right angle and the longest side in the triangle. Represents the diagonal distance between the endpoints of \(a\) and \(b\). |

| \( d \) | Distance | m, mm, ft, in | Generic symbol for distance; in coordinate form, \( d = \sqrt{(\Delta x)^2 + (\Delta y)^2} \) is just the Pythagorean Theorem in disguise. |

| \( \Delta x \) | Horizontal difference | m, mm, ft, in | Difference in x-coordinate between two points: \( \Delta x = x_2 – x_1 \). Plays the role of leg \(a\) when your axes are perpendicular. |

| \( \Delta y \) | Vertical difference | m, mm, ft, in | Difference in y-coordinate between two points: \( \Delta y = y_2 – y_1 \). Plays the role of leg \(b\). |

Unit consistency & field practice

- Always convert all legs into the same unit system (for example, all in mm or all in ft) before squaring and adding.

- In CAD and layout work, \(\Delta x\) and \(\Delta y\) often come directly from coordinate readouts; feeding them into \( c = \sqrt{\Delta x^2 + \Delta y^2} \) gives the straight-line distance.

- In field checks (for example, verifying that a slab is square), you typically measure both legs and the diagonal and compare \(c_{\text{measured}}\) to the theoretical value from \( a^2 + b^2 = c^2 \).

Once you are comfortable with the core notation, the rest of this guide shows how to apply the Pythagorean Theorem in realistic layouts, as detailed in the worked examples and the design tips & checks sections.

How the Pythagorean Theorem connects squares, distance & vectors

At its core, the Pythagorean Theorem is a statement about areas and right angles. If you construct a square on each side of a right triangle, the area of the square on the hypotenuse equals the sum of the areas on the legs. Translating “area of a square” into algebra (\(\text{area} = \text{side}^2\)) gives the familiar relationship \( a^2 + b^2 = c^2 \).

In engineering use, we rarely draw the squares; instead we treat the theorem as a compact way to combine perpendicular components. Whenever you have two orthogonal directions (say x and y on a drawing, or two perpendicular load components), you can treat them as legs of a right triangle and use the Pythagorean relationship to get the resulting magnitude.

Rearranging the theorem for unknown legs or diagonals

The most common algebraic forms boil down to “solve for the side you don’t know.” Starting from the basic relationship:

You can solve for any side as long as you know the other two:

In layout problems, you most often use \( c = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2} \) to get the diagonal from known offsets. In quality checks, you may invert the relationship to solve for what the diagonal should be, then compare it to measurements to see how far from square you are.

From triangles to distance formulas and vector magnitudes

The 2D distance formula is simply the Pythagorean Theorem written in terms of coordinate differences. Given two points \( (x_1, y_1) \) and \( (x_2, y_2) \), the horizontal separation is \( \Delta x = x_2 – x_1 \) and the vertical separation is \( \Delta y = y_2 – y_1 \). Treating these as legs of a right triangle gives:

The same geometry appears in vectors. If a 2D vector has components \(V_x\) and \(V_y\), then its magnitude is:

In both cases, the right angle between the axes is crucial. The theorem is built into the way we define perpendicular coordinate systems, which is why it appears so naturally in CAD distance tools, structural layout checks, and basic statics and dynamics calculations whenever you resolve loads into orthogonal components.

The Pythagorean Theorem assumes flat, Euclidean geometry and exact right angles. In curved spaces (for example, spherical geometry) or when your axes are not perpendicular, more general relationships like the law of cosines take over. But for almost all day-to-day engineering drawings and right-angle layouts, the Pythagorean Theorem plus a calculator gives accurate, fast distance estimates.

Worked examples using the Pythagorean Theorem in engineering

The examples below mirror typical questions people search for: “how do I find the diagonal?”, “how long does this cable need to be?”, or “how can I check if my slab is square?”. Each example follows the same pattern: set up a right triangle, identify the legs, and then apply \( a^2 + b^2 = c^2 \) or one of its rearrangements step by step.

Example 1 – Diagonal brace in a rectangular frame

A rectangular braced frame in a small equipment rack is 600 mm wide and 800 mm tall between connection centers. You want to add a diagonal brace from the lower left corner to the upper right corner. Neglecting connection eccentricities, what is the theoretical length of the brace?

- Identify the right triangle formed by the frame width, height, and diagonal brace.

- Assign \(a\) and \(b\) to the perpendicular legs and \(c\) to the diagonal.

- Apply \( c = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2} \) and compute the result.

Result: The brace should be 1,000 mm long between connection centers. In practice, you would adjust this slightly to account for connection details and fabrication tolerances, but the Pythagorean Theorem gives the exact geometric diagonal.

Example 2 – Cable length between offset supports

A light fixture is suspended from the ceiling using a cable that runs from a ceiling anchor point to the top of the fixture. The fixture’s center is 2.8 m below the ceiling and 1.2 m horizontally offset from the anchor point. Assuming the cable runs straight, how long does the cable need to be?

- Take the vertical drop as one leg and the horizontal offset as the other leg of a right triangle.

- Use \( c = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2} \) to find the cable length \(c\).

- Interpret the result and consider any extra length for terminations.

Result: The straight-line distance between the anchor point and the fixture top is about \(3.05~\text{m}\). In real installations, you would add some allowance for hardware and adjustment, but the Pythagorean Theorem gives the minimum geometric cable length.

Example 3 – Checking squareness of a concrete slab

A small rectangular slab is supposed to be 4.0 m by 5.0 m. To check if the formwork was square before pouring, a crew measured one diagonal and got 6.4 m. Does this match the theoretical diagonal from the Pythagorean Theorem, or is the slab out of square?

You know the design dimensions along both directions, so you can compute the theoretical diagonal and compare it to the field measurement. A significant difference would indicate that the corners are not at exactly 90°.

Result: The theoretical diagonal is about \(6.403~\text{m}\), very close to the measured \(6.4~\text{m}\). Within normal measurement tolerance, this is consistent with a square slab. If the measured diagonal had been far off (for example 6.1 m), the Pythagorean check would flag a squareness problem that might affect future framing or cladding.

Design tips, limits & sanity checks for the Pythagorean Theorem

Although the Pythagorean Theorem looks simple, most practical mistakes come from using it when the geometry is not a true right triangle, or from mixing units. The points below summarize the main assumptions and checks you should keep in mind when using it in design or field work.

The theorem only holds exactly when the angle between the legs is 90°. If your angle is slightly off, the computed diagonal will be slightly off; if the angle is far from 90°, the error can be large.

- Use the 3–4–5 rule (or scaled multiples like 6–8–10) in the field to set or verify right angles.

- If you know all three sides but the angle is unknown, use the Pythagorean relationship as a quick check: if \( a^2 + b^2 \) is much larger or smaller than \( c^2 \), the corner is not square.

- For non-right triangles, switch to the law of cosines rather than forcing the Pythagorean Theorem to fit.

Because the theorem involves squaring lengths, unit mistakes compound quickly. A mixed set of inches and millimeters, for example, can produce diagonals that are wildly wrong.

- Convert all dimensions to a single unit (for example, mm in structural details or ft in building plans) before squaring.

- For very large or very small dimensions, consider scaling to avoid numerical issues (for example, express everything in meters or millimeters consistently).

- Round only at the end of the calculation; premature rounding after squaring can introduce visible discrepancies in field checks.

The Pythagorean Theorem is exact for flat, 2D, right-angle geometry. As soon as your problem moves beyond that, you may need a different tool.

- For 3D diagonals (for example, corner-to-corner distance in a room or on a tank), extend the idea: apply the theorem twice or use \( d = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2 + c^2} \) for orthogonal x, y, z axes.

- For curved paths or non-orthogonal grids, use appropriate geometry (for example, law of cosines or geodesic distances) rather than assuming a right triangle.

- When tolerances are tight (precision machining, optics, etc.), combine the Pythagorean result with a tolerance analysis instead of treating the diagonal as exact.

For many everyday engineering tasks—laying out bracing, estimating cable runs, checking squareness, or computing 2D vector magnitudes—the Pythagorean Theorem is all you need. When your geometry becomes more complex, it still remains the intuitive backbone behind more general formulas, so mastering it pays off in later topics as well.

Pythagorean Theorem – FAQ

What is the Pythagorean Theorem in simple terms?

In simple terms, the Pythagorean Theorem says that in any right triangle, the square of the longest side (the hypotenuse) equals the sum of the squares of the other two sides. If the legs are \(a\) and \(b\) and the hypotenuse is \(c\), then \( a^2 + b^2 = c^2 \). It’s the rule behind “3–4–5” triangles and almost every “find the diagonal” calculation in basic geometry.

How do I know when I can use the Pythagorean Theorem?

You can use the theorem when two conditions are met: (1) you are dealing with a right triangle (one angle is exactly 90°), and (2) the two sides you know or want to combine are the sides that meet at that right angle. In coordinate problems, that usually means your x and y axes are perpendicular and your distances are measured along those axes.

Do the units matter in the Pythagorean Theorem?

The theorem itself is unit-agnostic, but you must keep units consistent. All sides must be expressed in the same units before squaring and adding; otherwise the result is meaningless. For example, convert everything to millimeters, meters, inches, or feet first, then apply \( a^2 + b^2 = c^2 \) and interpret the result in that unit.

How is the Pythagorean Theorem related to the distance formula?

The 2D distance formula \( d = \sqrt{(x_2 – x_1)^2 + (y_2 – y_1)^2} \) is just the Pythagorean Theorem applied to a right triangle whose legs are the horizontal and vertical differences between two points. In engineering drawings, CAD systems silently apply this relationship every time you use a “measure distance” tool in a standard x–y view.

References & further reading

- Standard geometry and trigonometry textbooks covering right triangles, distance formulas, and applications of the Pythagorean Theorem in coordinate geometry and vector analysis.

- Open educational resources (OER) such as university lecture notes and problem sets that provide proof sketches and a wide range of practice problems involving diagonals, layouts, and vector magnitudes.

- Structural and architectural layout guides that recommend using diagonal measurements and Pythagorean checks to verify squareness of slabs, frames, and panels in the field.