Fluid Mechanics · Continuity Equation

Continuity Equation – flow area, velocity & conservation of mass explained

The continuity equation is the formal statement of conservation of mass for flowing fluids, linking cross-sectional area, velocity, and density so you can relate flow rates through pipes, ducts, nozzles, and open channels.

Quick answer: what the continuity equation says

Core formula (steady, incompressible, single stream)

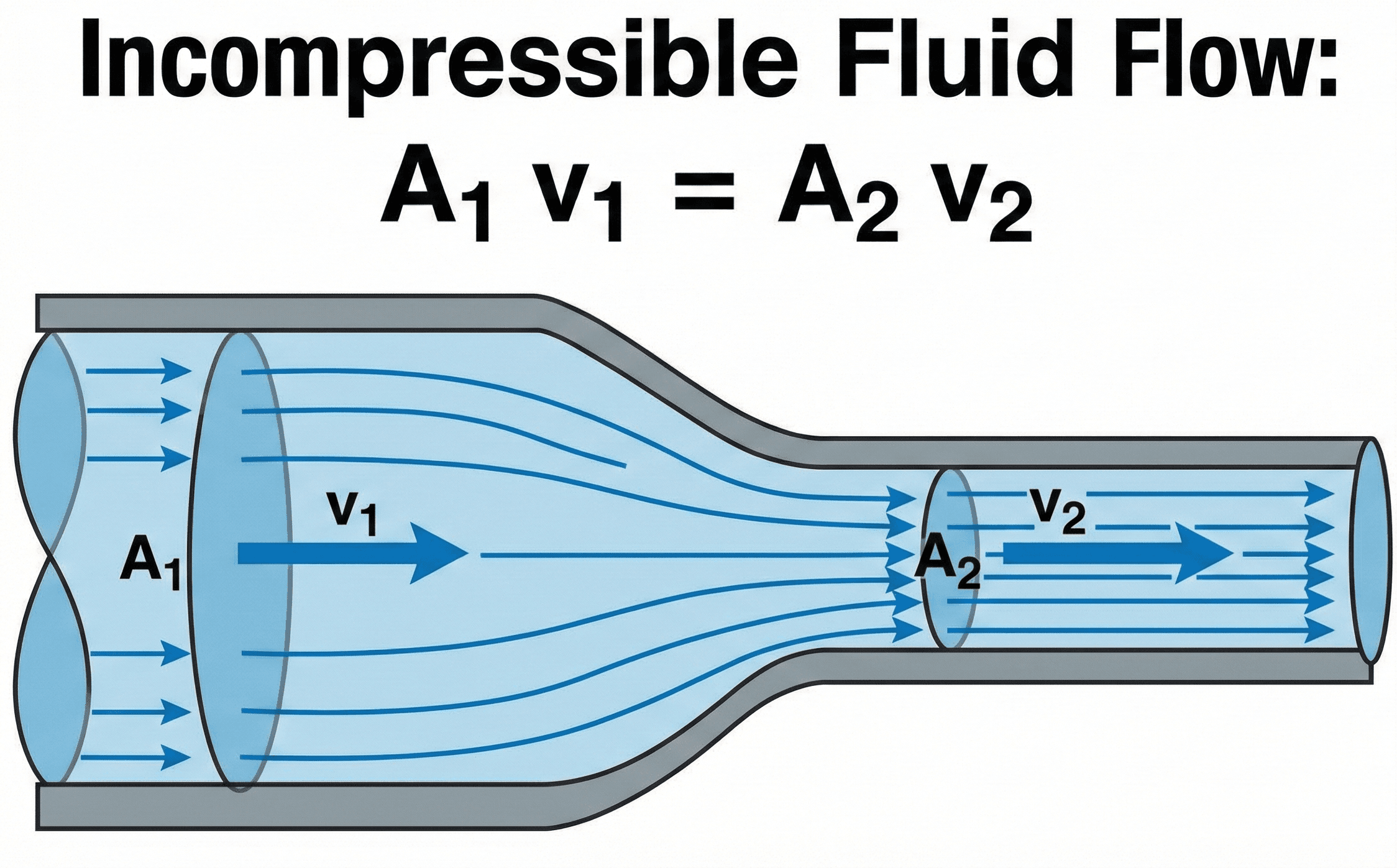

In everyday fluid mechanics, the continuity equation says that for a steady, incompressible flow with no leaks, the volumetric flow rate \(Q\) is the same at every cross-section, so if the area gets smaller the average velocity must increase, and if the area gets larger the velocity must decrease.

Physically, the continuity equation is just “what goes in must come out” written in math form. For a control volume that encloses a segment of pipe or duct, the mass of fluid cannot magically appear or disappear. If density is roughly constant (as it is for most liquid water systems) and the flow has settled into a steady pattern, the same volume of fluid that enters each second must leave each second. That is why engineers write \(A_1 v_1 = A_2 v_2\) for two sections along the same stream.

When density changes significantly, for example in gas pipelines, high-speed jets, or strongly heated flows, the more general statement is that \(\rho_1 A_1 v_1 = \rho_2 A_2 v_2\). In vector calculus form, the full continuity equation becomes \(\frac{\partial \rho}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (\rho \vec{v}) = 0\). But for many practical engineering systems—municipal water lines, HVAC ducts at modest speeds, cooling circuits, and laboratory rigs—the simple \(A v = \text{constant}\) version is more than enough.

Throughout this guide, we’ll treat the continuity equation as a design and troubleshooting tool. You’ll see how to compute unknown velocities from known pipe sizes, how to estimate flow splits at branches, and how to spot continuity violations that often signal measurement errors or leaks. We’ll reinforce these ideas with realistic worked examples that match typical homework and field calculations.

Symbols, subscripts & units in the continuity equation

In fluid mechanics, the continuity equation is often written in several equivalent forms, depending on whether you are tracking volumetric flow rate, mass flow rate, or a fully general field. At the 1D engineering level, the most common versions are \(Q = A v\) and \(A_1 v_1 = A_2 v_2\). In more advanced contexts, you’ll see \(\rho_1 A_1 v_1 = \rho_2 A_2 v_2\) or the differential form \(\frac{\partial \rho}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (\rho \vec{v}) = 0\). The table below summarizes the key symbols and units.

Common notation for continuity in pipes & ducts

| Symbol | Quantity | Typical SI unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(Q\) | Volumetric flow rate | m³/s | Volume of fluid passing a section per unit time. For uniform velocity across the section, \(Q = A v\). |

| \(A\) | Cross-sectional area | m² | Internal flow area at a given section, often computed from diameter \(A = \tfrac{\pi D^2}{4}\) for circular pipes or width × depth for rectangular ducts. |

| \(v\) | Average flow velocity | m/s | Mean fluid speed normal to the section. Defined so that \(Q = A v\); local velocity can vary over the area, but the average satisfies continuity. |

| \( \dot{m} \) | Mass flow rate | kg/s | Mass of fluid crossing a section per unit time. Related to volumetric flow via \(\dot{m} = \rho Q = \rho A v\). |

| \( \rho \) | Density | kg/m³ | Mass per unit volume. Roughly constant for many liquids, but can vary strongly for gases with pressure, temperature, or composition. |

| Subscripts 1, 2, 3… | Section labels | – | Identify different locations in a flow (upstream, downstream, branch lines, etc.), as in \(A_1 v_1 = A_2 v_2\) or \(Q_{\text{in}} = Q_{\text{out,1}} + Q_{\text{out,2}}\). |

Unit systems & practical notes

- SI practice: Use m, s, and kg. Typical water distribution problems use m³/s or L/s for \(Q\), m/s for \(v\), and m² for \(A\).

- U.S. customary units: You’ll see gal/min (gpm) or ft³/s for \(Q\), ft/s for \(v\), and ft² for \(A\). Be careful when converting mixed specifications (for example, gpm with pipe diameters given in inches).

- Liquids vs. gases: For liquids, \(\rho\) often changes little and \(A v = \text{constant}\) is acceptable. For gases with large pressure or temperature changes, use the mass form \(\rho A v = \text{constant}\).

Once you are comfortable with these symbols, the main work in real problems is choosing the right control volume and correctly accounting for all inlets and outlets, something we’ll practice in the worked examples section.

How the continuity equation enforces conservation of mass

At its core, the continuity equation is just conservation of mass applied to a flowing fluid. Imagine a fixed control volume that cuts through a pipe. Over a short time interval, some mass flows in and some mass flows out. If there are no leaks or accumulation of fluid inside, the rate at which mass enters must equal the rate at which mass leaves. This simple bookkeeping statement turns into a powerful design tool once you express it in terms of areas and velocities.

In the most general form for a control volume, continuity says that the rate of change of mass inside the volume plus the net mass flux out through the surfaces is zero. Under steady conditions (no net accumulation) and for a single inlet–outlet pair, this reduces to “mass flow in equals mass flow out”:

For incompressible fluids like water, density is effectively constant, so \(\rho_1 = \rho_2\) and it cancels out. That gives the familiar engineering form:

From control-volume mass balance to \(A v = \text{constant}\)

A quick way to see where the textbook continuity equation comes from is to start with a short pipe segment of length \(\Delta x\) and constant cross-sectional area \(A\). If the flow is steady and incompressible, the mass in the segment does not change in time, so the mass entering per unit time equals the mass leaving:

If the area changes from section 1 to section 2, the situation becomes:

In many design problems, you know three of the four quantities \((A_1, v_1, A_2, v_2)\) and use continuity to solve for the fourth. When you bring in energy equations (like Bernoulli) and head-loss models, you can also solve for unknown pressures and pumping power, but continuity is usually the first line you write.

Differential form: \(\frac{\partial \rho}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (\rho \vec{v}) = 0\)

In more advanced fluid mechanics, especially for compressible or unsteady flows, you encounter the continuity equation written in differential form:

Here, \(\rho = \rho(x,y,z,t)\) and \(\vec{v} = \vec{v}(x,y,z,t)\) describe how density and velocity fields vary in space and time. The divergence term \(\nabla \cdot (\rho \vec{v})\) measures the net outflow of mass from a tiny fluid element. If that net outflow is positive, the density in that element must decrease, and vice versa. For an incompressible fluid where \(\rho\) is constant, this reduces to \(\nabla \cdot \vec{v} = 0\), which still encodes the idea that fluid elements neither gain nor lose volume as they move.

In day-to-day engineering practice, you rarely need to write the full differential form yourself, but it underpins numerical solvers (CFD) and many analytic solutions. The key takeaway is that every time you treat a pipe, channel, or duct, the continuity equation is quietly enforcing conservation of mass behind the scenes—even when you only see the compact \(A v = \text{constant}\) form.

Worked examples using the continuity equation

These examples mirror the kinds of questions people ask most often: “If the pipe size changes, how fast is the fluid moving?”, “How do I convert a flow rate in L/s to velocity in m/s?”, and “How do multiple branches share flow?” Each problem follows a consistent workflow you can reuse in homework and design calculations.

Example 1 – Velocity change through a pipe contraction

Water at \(20^\circ\text{C}\) flows steadily through a horizontal pipe that contracts smoothly from an inside diameter of \(D_1 = 80~\text{mm}\) to \(D_2 = 40~\text{mm}\). The volumetric flow rate is \(Q = 0.010~\text{m}^3/\text{s}\). Assuming incompressible flow and a uniform velocity profile at each section, find the average velocities \(v_1\) and \(v_2\).

- Compute the cross-sectional areas at sections 1 and 2 from the diameters.

- Use \(Q = A v\) to find \(v_1 = Q / A_1\) and \(v_2 = Q / A_2\).

- Check that the results satisfy continuity and interpret the physical meaning.

Result: The average velocity is about \(2~\text{m/s}\) in the larger section and \(8~\text{m/s}\) in the smaller section. The area ratio is \(A_1/A_2 \approx 4\), so the velocity increases by the same factor, as expected from \(A_1 v_1 = A_2 v_2\).

Example 2 – Converting a specified flow rate to pipe velocity

A chilled-water line in a building is specified to carry \(Q = 2.0~\text{L/s}\) through a pipe of nominal inside diameter \(D = 25~\text{mm}\). Determine the average velocity in the pipe and comment on whether the value is typical for building services.

- Convert the flow rate to m³/s.

- Compute the cross-sectional area from the diameter.

- Apply \(v = Q / A\) and compare to common design ranges (1–3 m/s for many water systems).

Result: The average velocity is about \(4.1~\text{m/s}\), which is higher than the 1–3 m/s range often suggested for comfort and noise control in building piping. The continuity equation here flags that, for the specified flow rate, a larger pipe size might be worth considering to reduce velocity, friction losses, and potential vibration.

Example 3 – Flow split in a simple branch using continuity

A main water line (section 0) carries \(Q_0 = 0.030~\text{m}^3/\text{s}\) and splits into two branches, 1 and 2. Branch 1 has an inside diameter \(D_1 = 100~\text{mm}\); branch 2 has \(D_2 = 50~\text{mm}\). For a first-pass estimate, assume the branches have the same head loss per unit length and similar roughness, so flow splits roughly in proportion to cross-sectional area. Estimate the flow rates in each branch and the average velocities \(v_1\) and \(v_2\).

- Compute the cross-sectional areas \(A_1\) and \(A_2\).

- Assume \(Q_1 : Q_2 \approx A_1 : A_2\) and use \(Q_0 = Q_1 + Q_2\) to solve for \(Q_1\) and \(Q_2\).

- Compute velocities from \(v_i = Q_i / A_i\) and check continuity.

Result: Under the equal-head-loss assumption, each branch ends up with the same average velocity, about \(3.1~\text{m/s}\), while the larger branch carries four times the flow. Continuity enforces \(Q_0 = Q_1 + Q_2\), and the area-proportional estimate gives a quick first cut before you refine the design with detailed head-loss calculations.

Design tips, limits & checks when using the continuity equation

The continuity equation by itself is simple, but real systems layer on fittings, pumps, valves, leaks, and property changes. In design work you use continuity side-by-side with energy and momentum equations, but it still provides some of the fastest sanity checks in fluid mechanics. The points below highlight assumptions, common mistakes, and quick rules of thumb to keep your calculations realistic.

The familiar \(A v = \text{constant}\) form is not universal; it rests on several approximations that must be reasonable for your problem.

- Steady flow: Conditions are not changing rapidly with time; averages over a few seconds are representative.

- Incompressible fluid: Density is effectively constant between sections (true for most water problems, but not always for gases).

- No significant leaks: All the flow that enters your control volume exits through known outlets; bypass lines and leaks break the simple relation.

- Uniform average velocity: You can represent the cross-section with a single mean velocity; strong swirl or separation may require more care.

- Treating \(A_1 v_1 = A_2 v_2\) as valid for compressible gas flows with large pressure drops, where density changes significantly and \(\rho A v\) should be used instead.

- Mixing units for flow rates, areas, and velocities (for example, combining gpm with m²) and then “fixing” the answer with ad-hoc conversion factors instead of doing a clean conversion once.

- Ignoring additional inlets or outlets when performing a mass balance on a junction or tank, leading to continuity “violations” that are actually bookkeeping errors.

- Using continuity alone to size a system without checking velocities against erosion, noise, or cavitation limits suggested by codes and vendor data.

Before you commit to pipe sizes or interpret a strange measurement, run a few simple checks using continuity and typical design ranges.

- For cold-water building services, velocities of roughly 1–3 m/s are common; much higher velocities can mean noise, erosion, or excessive head loss.

- For HVAC ducts, check that air velocities remain within comfort and noise limits for the application (supply, return, main trunk vs. diffusers).

- If you have measurements of flow rate and velocity that do not satisfy \(Q \approx A v\), double-check instrument calibration, unit conversions, and whether the measurement locations match your assumed cross-section.

When you move into more advanced territory—such as compressible gas pipelines, rapidly varying transients in surge tanks, or complex open-channel systems—the same continuity ideas still apply, but you will write them in more general forms and often solve them numerically. The simple checks above, though, remain invaluable for spotting impossible numbers and guiding iteration, even in sophisticated CFD or hydraulic-network models.

Continuity Equation – FAQ

What is the continuity equation in simple terms?

In simple language, the continuity equation says that for a flowing fluid, mass cannot appear or disappear. For steady, incompressible flow through a pipe with no leaks, that means the same volume of fluid that enters per second must leave per second. Mathematically we write this as \(Q = A v\) and, between two sections on the same stream, \(A_1 v_1 = A_2 v_2\). Smaller area means faster flow; larger area means slower flow, so that the overall flow rate stays the same.

How do I use the continuity equation to solve pipe flow problems?

The basic workflow is: (1) sketch the piping or duct system and label all relevant cross-sections; (2) compute areas at each section from diameters or dimensions; (3) write a mass or volume balance such as \(Q_{\text{in}} = Q_{\text{out}}\) or \(A_1 v_1 = A_2 v_2\); (4) substitute known values for flow rate, area, or velocity and solve for the unknowns. For junctions, sum all inflows and outflows, for example \(Q_{\text{main}} = Q_{\text{branch1}} + Q_{\text{branch2}}\). Once you have velocities, you can combine them with other equations to find pressures and head losses.

When does \(A_1 v_1 = A_2 v_2\) stop being accurate?

The simple \(A_1 v_1 = A_2 v_2\) form assumes an incompressible fluid, steady conditions, and no unaccounted inlets, outlets, or leaks between sections. It starts to break down for highly compressible gas flows (for example, high-speed jets or gas lines with large pressure drops), rapidly unsteady situations (water hammer, surging), or systems with phase change or strong density gradients. In those cases, you should use the full mass form \(\rho_1 A_1 v_1 = \rho_2 A_2 v_2\) and, ultimately, the differential continuity equation coupled with appropriate state relations.

Is continuity the same as Bernoulli’s equation?

No. The continuity equation expresses conservation of mass; Bernoulli’s equation expresses conservation of mechanical energy along a streamline (relating pressure, velocity, and elevation). In many problems you use them together: continuity gives you how velocity changes with area, and Bernoulli then tells you how pressure must adjust when velocity changes. Mixing them up is a common mistake; continuity alone does not tell you anything about pressure unless you also bring in energy and head-loss relations.

References & further reading

- Standard fluid mechanics textbooks that introduce continuity, Bernoulli’s equation, and head-loss relationships in the context of internal and external flows.

- Online lecture notes and problem sets from university fluid mechanics courses, many of which include detailed continuity equation examples with multiple inlets and outlets.

- Manufacturer design guides and application notes for pumps, valves, and piping systems, which show how continuity, energy, and friction equations are combined in real-world sizing calculations.