Key Takeaways

- Intersection Design combines control selection, geometry, multimodal design, and operational/safety checks to produce buildable plans.

- The process starts with context + constraints (speeds, users, right-of-way, utilities) and demand (turning movements, trucks, pedestrians).

- Good designs balance capacity, queue storage, accessibility, sight distance, and constructability.

- Your final package typically includes layout + profiles, signing/markings, signal exhibits (if applicable), and a clear design narrative.

Table of Contents

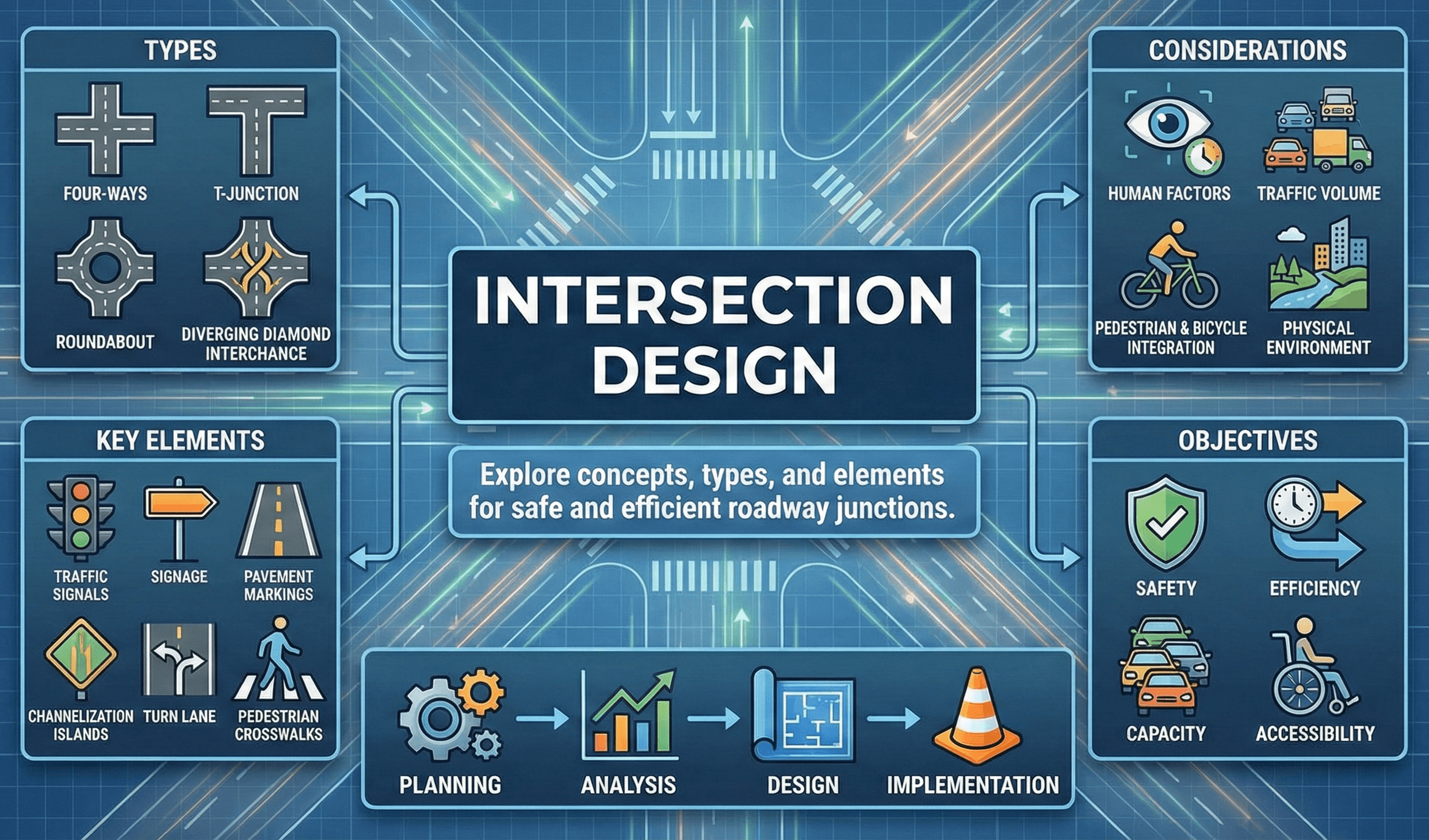

Featured diagram

Introduction

Intersection Design is where transportation engineering becomes “real” on the ground: every project forces you to reconcile how people actually move with how pavement, curbs, signals, and right-of-way can be built. A complete design is more than drawing lanes—it’s a structured workflow that starts with context and data, then moves through control selection, geometric layout, multimodal features, operations, safety checks, and finally a set of plans a contractor can build and an agency can maintain. This page walks through that workflow from start to finish, using practical decision points engineers face on everyday projects: lane configuration, turning paths, storage length, sight distance, curb radii, crosswalk placement, and (when applicable) signal phasing and timing basics.

What is Intersection Design?

Intersection Design is the engineering process of creating a safe, functional, and buildable layout where two or more roadways meet. It includes the physical geometry (lane arrangement, widths, curb returns, medians, and profiles), the control method (stop/yield, signal, roundabout, or other control), and the supporting elements that make the intersection legible and accessible (signing, markings, lighting, ADA curb ramps, pedestrian crossings, drainage, and access management). A good design produces predictable movements for drivers, safe crossing opportunities for pedestrians, comfortable geometry for cyclists (or a clear alternative route), and acceptable operations for the design year.

Most agencies expect intersection design decisions to be documented: the “why” behind lane additions, the reason a curb return radius is chosen, how queues were checked against storage, and how accessibility requirements were met. Even on smaller projects, a short design narrative paired with clear plan sheets can prevent costly redesign later.

Treat every intersection as a system with three layers: context (users and speeds), geometry (what movements are physically encouraged), and control (how right-of-way is assigned). If one layer is ignored, the others usually fail.

Project inputs you need before you draw lanes

Intersection design is data-driven. Before selecting lanes or curb lines, assemble a complete “inputs package” so you are not redesigning repeatedly as missing constraints appear.

1) Context and performance goals

Document the speed environment, surrounding land use, and who uses the intersection. A downtown main street with frequent pedestrian crossings will be designed differently than a rural highway intersection. Confirm the project goals early: safety-driven retrofit, congestion relief, multimodal access, freight route accommodation, or a combination.

2) Base mapping and constraints

Start with an accurate survey or base map: right-of-way lines, property corners, existing curb and pavement edges, utilities (including poles, cabinets, inlets, manholes), drainage paths, and key features like trees, walls, and buildings. Identify the “hard constraints” that control how much geometry can move.

3) Demand data

Collect turning movement counts for typical peak periods (AM, PM, and any special peaks like school dismissal). Record heavy vehicle percentages, buses, and oversize loads if applicable. Include pedestrian and bicycle volumes (even if low), because crossings and ramps must still meet accessibility requirements.

4) Safety history

Review crash data for patterns: rear-end clusters, left-turn angle crashes, pedestrian/bike conflicts, run-off-road, or nighttime issues. Knowing the dominant crash types helps you focus design changes where they matter most.

Before any layout work, verify you can answer: What are the controlling movements? What are the controlling vehicles? What are the controlling constraints (ROW/utilities/drainage)? If any of those are unknown, pause and resolve them.

Selecting intersection control

Control selection sets the “rules of engagement” at the intersection. The goal is not to chase a single performance metric; it is to select a control that is feasible within constraints, supports safe and predictable behavior, and meets operational needs for the design period.

Control options commonly used

- Two-way stop control (TWSC): Minor street stops; major street flows.

- All-way stop control (AWSC): All approaches stop; often used in low-speed grids.

- Traffic signal: Time-separated right-of-way assignment; supports heavier demand and coordinated corridors.

- Roundabout: Yield control with circulating flow; geometry manages speed and conflict angles.

- Restricted movements: Prohibiting certain turns, channelization, or right-in/right-out controls.

Feasibility screening (do this early)

Even before detailed analysis, screen alternatives using constraints: available right-of-way, grades, nearby driveways, drainage low points, transit stops, railroad crossings, bridge/culvert limits, and utility conflicts. Some controls can be eliminated quickly if they cannot be built or would create unacceptable downstream impacts.

Choosing control based on a single “typical” peak hour without checking storage, downstream spillback, or pedestrian crossing needs often leads to a design that looks good on paper but fails in the field.

Geometric layout: lanes, alignment, and turning paths

Geometry determines how drivers position their vehicles, how fast they enter the intersection, and how predictable conflicts become. Start geometry with the design vehicle and the controlling movement, then build outward to the full lane configuration.

Step 1: Confirm the design vehicle and turning templates

Identify the largest vehicle that routinely uses the intersection (e.g., WB-50/WB-67 trucks, buses, fire apparatus) and whether occasional oversize vehicles must be accommodated. Turning paths often control curb return radii, lane alignment, and channelization islands.

Step 2: Set approach lane configuration

Use traffic demand and operations goals to determine the number of through lanes and whether dedicated turn lanes are needed. For turn lanes, verify both bay taper and storage length are adequate for expected queues and do not block upstream driveways or intersections.

Step 3: Define curb return radii and corner geometry

Corner geometry influences turning speed and pedestrian crossing distance. Larger radii reduce encroachment for trucks but can increase turning speed for passenger cars. Use turning path checks to right-size radii rather than defaulting to an overly large value.

Step 4: Align centerlines and manage offsets

Misaligned approaches can increase conflict and driver confusion. Where offsets exist (e.g., staggered side streets), evaluate whether realignment or channelization can improve legibility and safety.

Perform turning path checks early and often. A clean lane plan that fails a bus or truck turn can force late-stage curb and drainage redesign.

Pedestrian, bicycle, and ADA design (make it work for real users)

Multimodal features are not “add-ons.” They affect geometry, signal operations, and safety outcomes. At a minimum, intersection design must provide accessible pedestrian routes that connect logically to sidewalks and crossings.

Pedestrian crossings and curb ramps

Place crosswalks where they are expected and where sight lines are good. Provide ADA-compliant curb ramps aligned to the crosswalk, with detectable warnings and landing areas that do not drain across the ramp. Ensure grades, cross slopes, and ponding risks are addressed.

Refuge islands and crossing distance

Where crossing distances are long or speeds are higher, refuge islands can reduce exposure and improve comfort. If islands are used, ensure they are wide enough for a pedestrian to wait safely and that ramp alignments remain intuitive.

Bicyclist accommodation

Intersection treatment depends on roadway context: shared lanes, bike lanes, separated facilities, or parallel routes. Whatever the approach, the intersection should provide a clear and consistent path. Avoid forcing cyclists into ambiguous merges at the conflict point.

Trace the pedestrian path end-to-end: sidewalk → ramp → crosswalk → refuge (if any) → ramp → sidewalk. Any gap, awkward angle, or ponding point will show up immediately during plan review and field use.

Operations: capacity, delay, and queue storage

Operational analysis supports design decisions like lane counts, turn bay lengths, and (if signalized) the phasing plan. While detailed procedures vary by agency and software, the core idea is consistent: compare demand to service capacity, then verify queues fit within available storage.

Lane group concepts (why movements are analyzed in groups)

Intersection approaches are typically analyzed by lane groups: sets of lanes serving the same movement(s) with similar control and saturation behavior. Examples include “eastbound through,” “northbound left,” or a shared “through+right” lane group.

A simple capacity relationship for a signalized movement

A common way to express the service capacity of a signalized lane group is based on saturation flow and the share of effective green time it receives. In simple form:

- \(c\) Movement capacity (veh/h for the lane group)

- \(s\) Saturation flow rate (veh/h of effective green, typically per lane or lane group)

- \(g\) Effective green time for the movement (s)

- \(C\) Cycle length (s)

This relationship is useful for intuition: if effective green is a small fraction of the cycle, capacity drops; if you add lanes or improve saturation flow, capacity rises. Real analyses add additional adjustments and performance measures (like delay and level of service), but the fundamental dependencies remain the same.

Queue storage checks (turn bays and spillback)

Regardless of control, verify the predicted queue for each movement fits within available storage. If the queue exceeds storage, it can block adjacent lanes or upstream intersections, causing operational breakdown and increasing crash risk. Storage is a geometric feature—if it’s too short, the intersection may fail even if “capacity” looks acceptable.

Always check the worst case for storage: the peak 15 minutes can be more important than the peak hour average, especially near schools, event venues, and freeway ramps.

Signal design basics (when the intersection is signalized)

If the selected control is a traffic signal, the design expands beyond lanes and curbs into phasing, detection, pedestrian timing, and equipment placement. The geometric plan should support the signal plan, not fight it.

Phasing and movements

Phasing determines which movements run together. Start by identifying which movements conflict and which can operate concurrently. Consider protected/permissive left turns, pedestrian crossing phases, and whether overlap or lagging options are permitted by the agency.

Pedestrian timing inputs

Pedestrian intervals depend on crossing distance and assumed walking speed per agency guidance. Ensure crosswalk lengths match the geometric design and that pedestrian pushbuttons are accessible and placed where users naturally wait.

Detection, stop bars, and equipment placement

Stop bar location affects sight lines, turning paths, and crosswalk placement. Detection zones (loops, video, radar) must match the expected queue locations and lane use. Poles, mast arms, and cabinets must be located within feasible right-of-way and outside critical clear zones where required.

Designing geometry first and “adding the signal later” can force stop bar relocations, crosswalk changes, and pole conflicts that unravel the plan set. Coordinate signal exhibits early—especially at constrained corners.

Safety checks: sight distance, speed management, and conflict control

Safety checks are the difference between a plan that looks good and one that performs well in the field. The appropriate checks depend on control type and context, but several items appear on most intersection projects.

Sight distance and visibility

Verify drivers can see conflicting vehicles, pedestrians, and signal indications with enough time to respond. Sight triangles can be affected by landscaping, walls, parked vehicles, and vertical curvature. If sight is limited, geometry or access control changes may be needed.

Speed management through geometry

Approach alignment, lane widths, and corner radii influence operating speeds. If speeds are too high for the context, use geometric and signing/marking strategies that communicate a lower speed environment consistently.

Channelization and wrong-way prevention

Islands, medians, and markings can reduce ambiguity, guide drivers into correct lanes, and protect pedestrians. For divided facilities, ensure the intersection clearly communicates where drivers should enter, stop, and turn—especially at night.

If a first-time driver arrives at the intersection at night in the rain, can they instantly tell: which lane to be in, where to stop, and who has the right-of-way? If not, improve lane assignment signing, markings, and channelization.

Work with real numbers

Engineering calculators & equation hub

Jump from theory to practice with interactive calculators and equation summaries covering civil, mechanical, electrical, and transportation topics.

Putting it all together: plans, exhibits, and final deliverables

A complete intersection design ends with a plan set and documentation that reviewers can approve and contractors can build. Deliverables vary by agency, but most intersection packages include a clear layout, profiles and grades where needed, and sheets that fully describe how users will be controlled.

Typical plan sheets

- Overall intersection layout: lane configuration, curb lines, medians/islands, striping extents, and key dimensions.

- Profiles and grading: vertical alignment, curb/gutter grades, and drainage compatibility (especially at low points).

- Signing and markings: lane assignment, stop/yield control, crosswalk markings, and legends.

- ADA details: ramp types, landing areas, detectable warnings, and accessible routes.

- Signal exhibits (if signalized): pole locations, heads, detection, phasing notes, and any special equipment.

- Traffic control / staging: how the intersection will remain functional during construction.

Design narrative (what reviewers look for)

A short narrative that summarizes key assumptions and checks can save time during review: counts and design year, lane group assumptions, storage checks, design vehicle turning path summary, sight distance considerations, and any major constraint decisions. The narrative should match the drawings—no surprises.

Keep a running “decision log” while you design (control rationale, lane additions, radius choices, storage changes). When plan review arrives, you can translate that log into a concise narrative instead of reconstructing decisions from memory.

Relevant standards and design references

Intersection Design is guided by widely used transportation references. Agencies often adopt these directly or through local supplements; always confirm the governing manuals for your jurisdiction.

- HCM (Highway Capacity Manual): Operational analysis methods for intersections, including delay, capacity concepts, and lane group framework for common controls.

- MUTCD: National guidance for traffic control devices—signing, pavement markings, and signal indications that shape how an intersection communicates with users.

- AASHTO “Green Book”: Geometric design guidance for alignment, sight distance, lane widths, and intersection geometry fundamentals.

- FHWA intersection and safety guidance: Practical resources on safety treatments, access management considerations, and implementation-focused best practices.

- Local agency design manuals: State DOT or city standards that set default dimensions, typical sections, ADA details, and signal equipment conventions.

Frequently asked questions

Start by assembling your inputs package: base mapping with constraints, turning movement counts, speed environment, and design vehicle needs. Those items determine feasibility and prevent repeated redesign when conflicts or missing data appear later.

Dedicated turn lanes are typically justified when turning demand creates unacceptable delay or blocks through traffic, or when safety and lane assignment clarity improves with separation. Even with sufficient capacity, storage length and spillback risk can make a dedicated bay necessary.

The most common misses are queue storage vs. available bay length, turning paths for the controlling vehicle, and end-to-end ADA route continuity. Sight distance and equipment conflicts (poles, cabinets, inlets) are also frequent review comments when not coordinated early.

Most plan sets do not include full equations, but agencies often expect the supporting analysis to be available in reports or calculation files. What matters is that the drawings reflect the outcomes: lane needs, storage, crossings, and clear control details.

Prioritize legibility: consistent lane alignment, clear lane assignment signing, intuitive channelization, and markings that match the geometry. If drivers can predict where they should be and what happens next, operating speeds and conflicts typically become more manageable.

Summary and next steps

Intersection Design is a structured workflow that turns real-world constraints and travel demand into a safe, buildable crossing. The most reliable path is to start with context and inputs, then select feasible control, shape the geometry around turning paths and storage, integrate pedestrian/ADA needs end-to-end, and finally confirm operations and safety checks match the design intent. When those steps are coordinated early, the result is a plan set that reviewers can approve and that works in the field without constant operational surprises.

If you are learning or reviewing intersection design, focus on the practical connections: how lane configuration changes queue behavior, how curb returns affect both trucks and pedestrians, and how control details like stop bars and crosswalk placement influence visibility and compliance. The best designers develop a repeatable checklist and a habit of verifying assumptions with quick checks before investing time in detailed drafting.

Where to go next

Continue your learning path with these next steps in Transportation Engineering.

-

Traffic Flow Theory

Build stronger intuition for how demand, capacity, and congestion form—useful when you evaluate intersection operations and queue storage.

-

Signal timing fundamentals

Learn how phasing, cycle length, and effective green shape movement service and delay at signalized intersections.

-

Access management basics

Understand how driveway spacing and nearby access points influence intersection performance, safety, and turning lane needs.

Work with real numbers

Engineering calculators & equation hub

Jump from theory to practice with interactive calculators and equation summaries covering civil, mechanical, electrical, and transportation topics.