Key Takeaways

- Thickness isn’t a guess: Pavement design thickness comes from a workflow: choose pavement type → estimate design traffic → quantify support and materials → size layers to meet reliability/performance targets.

- Traffic drives structure: A small number of heavy trucks can govern design; converting mixed traffic to a cumulative load metric (often ESALs) is a core step.

- Subgrade + drainage matter: Weak or wet support conditions can dominate thickness; stabilizing soils and improving drainage can be as impactful as adding asphalt or concrete.

- Method depends on context: Flexible, rigid, composite, and other systems each have “best-fit” use cases tied to loads, climate, construction constraints, and life-cycle cost.

Table of Contents

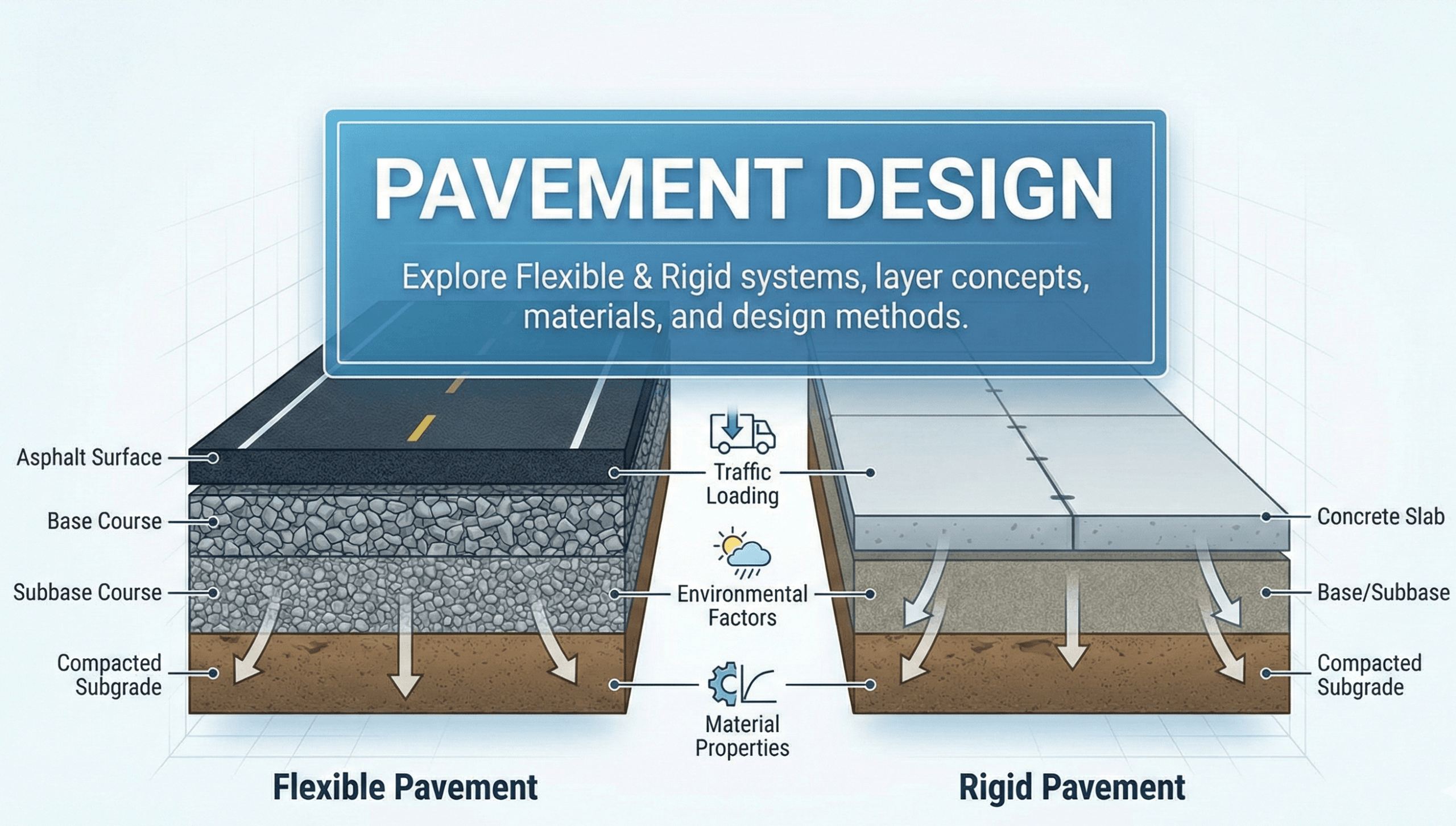

Featured diagram

Image prompt (editor only): Create a clean, engineering-style diagram of a pavement cross-section with labeled layers (surface course, base, subbase, subgrade) and arrows showing wheel load distribution; include a small inset showing traffic loading (truck axle) and a note for “design life” and “drainage.”

Introduction

Pavement design is the process transportation engineers use to choose a pavement type and determine layer thicknesses so a roadway, parking lot, industrial yard, or airfield pavement will perform reliably for a planned service life. “Performance” includes carrying traffic loads without excessive cracking, rutting, faulting, or roughness—while also managing water, temperature, construction variability, and maintenance realities.

If you’ve ever asked “How thick should the asphalt be?” or “When do we choose concrete instead?” you’re already asking pavement design questions. This guide walks through the actual design workflow: selecting pavement type, estimating traffic loadings, evaluating subgrade and materials, calculating thickness (with the key relationships that matter), and applying common standards used in transportation engineering practice.

What is pavement design?

Pavement design is the engineering method used to determine the pavement structure (layer materials and thicknesses) needed to support forecast traffic loads under local environmental conditions for a chosen design life and reliability. The design output is not just “total thickness”—it is a layered system specification (for example, asphalt surface thickness, base type and thickness, subbase thickness, and any subgrade treatment).

Good pavement design balances three goals: structural capacity (carry loads), durability (resist moisture, temperature effects, and aging), and constructability/maintainability (build it consistently and keep it performing with realistic maintenance).

If you can’t explain why each layer is there (load distribution, drainage, frost protection, working platform, etc.), you probably don’t have a complete pavement design yet—you have a thickness number without a mechanism.

Types of pavements and when to use each

Pavement design starts with selecting the pavement type that fits the project’s loading, climate, and agency constraints. The most common systems are flexible (asphalt), rigid (concrete), and composite (asphalt over concrete or other combinations). Some projects also use perpetual pavement concepts, stabilized bases, or unbound/aggregate surfaces for low-volume applications.

Flexible pavements (asphalt)

Flexible pavements distribute wheel loads through layered asphalt and granular materials. They are widely used for roads and parking areas because they are adaptable, fast to construct, and easy to rehabilitate with overlays. They can perform extremely well, but rutting, fatigue cracking, moisture damage, and thermal cracking must be considered—especially under heavy loads or extreme temperatures.

Rigid pavements (concrete)

Rigid pavements rely on slab action to carry loads, so the concrete slab itself provides most of the structural capacity. They often perform well under heavy traffic and high temperatures and can offer longer structural life, but joints, faulting, curling/warping, and construction details (dowels, tie bars, joint spacing, base support) are central to success.

Composite pavements

Composite systems combine materials to capture benefits of each (e.g., asphalt overlay on concrete for improved ride and noise, or asphalt on a cement-treated base for high stiffness). Pavement design for composites typically needs a clear understanding of the existing structure, bonding conditions, reflection cracking risk, and drainage.

Low-volume and special-purpose pavements

For low-volume roads, temporary haul routes, shoulders, or access roads, an aggregate surface or thin asphalt system may be appropriate. Industrial yards, ports, and intermodal facilities may require thicker sections, special surface mixes, or rigid pavements due to slow-moving heavy loads and high shear stresses.

| Pavement type | Best-fit scenarios | Common design “drivers” | Typical rehab strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexible (asphalt) | Most roadways, parking lots, staged construction | ESALs, rutting/fatigue, subgrade moisture, mix selection | Mill & overlay, structural overlay, patching |

| Rigid (concrete) | Heavy truck corridors, intersections, high temps | Slab thickness, jointing, k-value/support, fatigue | Diamond grind, slab repair, overlays |

| Composite | Overlays of existing pavements, noise/ride improvements | Bonding, reflection cracking, existing condition | Overlay renewals, crack control systems |

If heavy trucks brake/turn frequently (intersections, terminals, loading docks), consider rigid pavement or special high-stability asphalt solutions—pavement type selection is part of pavement design, not a separate decision.

What you need before you can design thickness

Pavement thickness is calculated from inputs that describe loading, support, and materials. If any of these are missing, thickness becomes guesswork. Before you run a pavement design method, collect (or reasonably assume, with documentation) the items below.

Traffic inputs

- Functional class / facility type: local road, arterial, freeway, industrial yard, etc.

- Design life: commonly 15–30 years depending on agency and facility type.

- Truck volume and growth: AADT, % trucks, growth rate, design lane distribution.

- Axle loading assumptions: typical axle spectra or default equivalency factors if spectra are unavailable.

Subgrade and foundation inputs

- Subgrade strength/stiffness: CBR, resilient modulus (Mr), or other agency-defined parameter.

- Moisture and drainage: groundwater, capillary rise potential, ditch performance, edge drains.

- Frost susceptibility: freeze-thaw depth, soil gradation/plasticity (where applicable).

Material and construction inputs

- Layer material types: asphalt mix class, base/subbase gradations, stabilized layer options.

- Quality and variability: expected compaction and material property variability (affects reliability).

- Agency constraints: minimum thicknesses, standard sections, permitted layer types.

Designing thickness using “typical” subgrade properties without verifying moisture conditions can under-design the pavement. A subgrade that is strong when dry can behave very differently when saturated.

Traffic loading for pavement design

In pavement design, mixed traffic must be converted into a cumulative measure of damage over the design life. A common approach is to convert trucks to Equivalent Single Axle Loads (ESALs) (typically 18-kip single-axle ESALs). Some modern methods use axle load spectra directly, but ESAL-based thinking is still widely used because it ties to many standard pavement design procedures.

Step-by-step: estimating design ESALs (conceptual workflow)

- Start with traffic counts: AADT and the percentage of trucks (or vehicle classifications).

- Forecast growth: Apply a growth rate over the design life (or use agency-provided forecasts).

- Apply distribution factors: directional distribution (D) and design lane distribution (L).

- Convert trucks to ESALs: use an equivalency factor (or axle spectra method) to compute cumulative ESALs.

- \(W_{18}\) Cumulative 18-kip ESALs over the design life (dimensionless count)

- \(\text{AADT}_{y}\) Annual average daily traffic in year \(y\) (vehicles/day)

- \(\%\,\text{trucks}\) Fraction of traffic that is trucks (0–1)

- \(D\) Directional distribution factor (0–1; one direction share)

- \(L\) Design lane distribution factor (0–1; trucks in design lane)

- \(\text{EF}\) Truck-to-ESAL equivalency factor (depends on axle loads / spectra)

If you don’t have axle spectra, your biggest uncertainty is often the equivalency factor. Document your assumptions, and use conservative—but defensible—values for truck-heavy corridors or industrial access routes.

Subgrade support, drainage, and why they control thickness

Pavement design is as much about the foundation as it is about the surface material. The same asphalt thickness can perform very differently over a stiff, well-drained subgrade versus a weak, wet subgrade. Designers quantify support using parameters such as CBR, resilient modulus (Mr), or a modulus of subgrade reaction (k-value) for rigid pavement analysis.

How engineers represent subgrade strength

- CBR (California Bearing Ratio): common for subgrade and base characterization, especially in agency workflows.

- Resilient modulus (Mr): stiffness measure used in mechanistic design; reflects stress-dependent behavior.

- k-value: support parameter often used in rigid pavement design models; influenced by base and subgrade.

Drainage considerations that directly affect design

- Infiltration paths: pavement joints, shoulder interfaces, and edge cracking allow water into the structure.

- Permeability + outlets: permeable bases need functioning outlets; otherwise they can trap water.

- Seasonal moisture: wet seasons can reduce subgrade stiffness and increase damage accumulation.

If drainage is marginal (flat grades, high groundwater, poor outlets), treat the pavement as if the subgrade is weaker than its lab result. Real-world moisture conditions often govern pavement performance.

How pavement thickness is calculated

“Pavement thickness” is typically the output of a design method (agency standard, AASHTO-based approach, or mechanistic-empirical procedure). While the exact equations and calibration differ by method, the underlying idea is consistent: traffic demand must be matched by structural capacity, adjusted for reliability and serviceability/performance.

Flexible pavement thickness: structural capacity concept

Many flexible pavement design workflows express structural capacity using a Structural Number (SN), which represents the combined contribution of each layer to carrying load. Once the required SN is determined from traffic and support inputs, the designer selects layer thicknesses that meet or exceed that SN.

- \(SN\) Required structural capacity index for the pavement section

- \(a_i\) Layer coefficient (strength contribution per thickness; depends on material type)

- \(D_i\) Layer thickness (often inches in many agency SN formulations)

- \(m_i\) Drainage coefficient (adjusts granular layer contribution for drainage quality)

In practice, you do not “pick” the layer coefficients randomly—agencies publish typical values by material class, and mechanistic-empirical methods infer equivalent stiffness effects through material moduli and performance models. Either way, the thickness decision is tied to traffic, support, and reliability.

Rigid pavement thickness: slab action and support

Rigid pavement design focuses on selecting a slab thickness that limits critical stresses and fatigue damage under axle loads, while accounting for support conditions (often represented by k-value), load transfer at joints, and temperature-related curling/warping. Agencies use standardized procedures or mechanistic-empirical models calibrated to field performance.

If the project is jointed concrete pavement, thickness and joint design are inseparable. Poor joint details can cause faulting and pumping even when slab thickness seems adequate.

What “thickness” actually means on plans

A complete pavement design thickness output should specify:

- Surface type and thickness (asphalt lift structure or concrete slab thickness).

- Base type and thickness (aggregate base, asphalt-treated base, cement-treated base, etc.).

- Subbase type and thickness (where used for frost/drainage/constructability).

- Subgrade treatment (stabilization, undercut and replace, geosynthetics if applicable).

- Drainage features and edge details (outlets, shoulders, joint sealing, etc.).

Pavement design workflow you can follow

Below is a practical pavement design workflow that matches how many agencies and consultants approach real projects. It is deliberately structured as “decision + calculation + check” so you can trace how thickness is justified.

- Define the facility and constraints: roadway class, expected trucks, speed, available right-of-way, utility constraints, construction staging, and agency standard sections.

- Select pavement type: flexible vs. rigid vs. composite based on loads, climate, constructability, and life-cycle considerations.

- Set design life and reliability: choose targets consistent with agency policy and consequence of failure.

- Estimate traffic loading: compute ESALs or axle spectra for the design lane over design life.

- Characterize subgrade and drainage: determine support parameters (CBR/Mr/k) and account for seasonal moisture/drainage quality.

- Select materials: choose mix types and base/subbase options consistent with performance and local availability.

- Compute required structure: determine required SN (flexible) or slab thickness (rigid) using the selected method.

- Choose layer thicknesses: convert required structure into buildable layer thicknesses that meet minimums and constructability.

- Check performance and details: verify drainage, frost protection (if needed), rutting/cracking risk (flexible), joint and load transfer behavior (rigid), and maintainability.

- Document assumptions: record traffic inputs, factors, subgrade parameters, and the rationale for the final section.

Before finalizing pavement thickness, ask: “If my traffic estimate is 20% higher, or the subgrade is wetter than expected, do I still have a reasonable section?” Sensitivity thinking is part of responsible pavement design.

Worked example: sizing a flexible pavement section (concept demonstration)

This example is intentionally simplified to show the pavement design logic that leads to thickness. Agencies differ on exact coefficients and procedures, so treat the numbers as a demonstration of structure—then align inputs with your governing standard.

Example

Given: A two-lane roadway with a defined design lane. Design life \(N=20\) years. Estimated cumulative design traffic \(W_{18}=2.0\times10^{6}\) ESALs. Subgrade characterized as moderate support (e.g., a CBR/Mr consistent with an agency “medium” category). Drainage is fair (not excellent). The agency provides typical layer coefficients for asphalt and aggregate base.

Goal: Choose asphalt surface thickness \(D_1\) and aggregate base thickness \(D_2\) (and subbase if needed) to meet the required structural capacity for the chosen method.

Step 1: determine required structural capacity (SN requirement)

Using the governing standard (often an AASHTO-based procedure or an agency chart), the designer determines a required \(SN_\text{req}\) based on \(W_{18}\), reliability, serviceability loss, and subgrade support. For demonstration, assume the method yields:

Step 2: select a buildable layer plan and check SN

Suppose the agency typical coefficients are \(a_1 = 0.44\) for asphalt and \(a_2 = 0.14\) for aggregate base, and drainage is fair so \(m_2 = 0.95\). Try a section with 6 in asphalt and 10 in base:

Since \(3.97 < 4.2\), the section is slightly under the required capacity. Increase asphalt to 7 in (keeping base at 10 in):

Now \(4.41 \ge 4.2\), so the structure meets the capacity target. The final pavement design would still require checks for minimum lift thicknesses, constructability (lift breaks), drainage details, and local agency requirements.

Pavement design is not “plug and chug.” Your governing standard defines how \(SN_{\mathrm{req}}\) is obtained, what coefficients are allowed, and what minimum thicknesses apply. Always align example logic to your agency’s method before using it on a real project.

Common pitfalls and engineering checks in pavement design

Many pavement failures trace back to a small set of repeat issues. Use the checks below to stress-test your pavement design before it becomes a plan set.

Common pitfalls

- Unit and definition mismatches: mixing ESAL conventions, inconsistent thickness units, or misapplied distribution factors.

- Underestimated truck loading: industrial traffic, detours, or development-driven growth not captured in the forecast.

- Ignoring drainage: no edge outlets, trapped water in permeable bases, or shoulder details that invite infiltration.

- Assuming uniform subgrade: weak pockets, expansive soils, or seasonal moisture swings not addressed in the section.

- Detail blind spots: transitions, intersections, utility cuts, and widening joints often crack first if not detailed for pavement behavior.

Engineering checks (quick sanity tests)

Compare your final section to known-performing standard sections for similar traffic and subgrade. If your design is dramatically thinner, confirm traffic assumptions and drainage/subgrade inputs; if dramatically thicker, confirm you’re not double-counting conservatism.

| Design element | What to verify | Why it matters | Quick check |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traffic loading | Truck %, growth, D & L factors, equivalency assumptions | Heavy loads dominate damage accumulation | Does the design lane truck volume “feel right” for facility type? |

| Subgrade support | CBR/Mr category, wet-season condition, variability | Weak/wet support increases required thickness | Do field observations match lab assumptions? |

| Drainage | Outlets, edge details, permeable layers | Moisture accelerates distress | Where does water go after it enters the pavement? |

| Layer structure | Lift thicknesses, minimums, material availability | Buildability affects actual performance | Is each lift thickness practical for compaction and paving? |

Pavement design should explicitly address “high-stress zones” (stops, turns, slow heavy loads). A uniform section may be fine for midblock segments but inadequate at intersections or industrial entrances.

Visualizing the pavement design decision chain

A useful way to understand pavement design is to visualize it as a decision chain where each input narrows the solution space: facility type sets the baseline; traffic loading sets demand; subgrade and drainage set foundation capacity; materials set layer performance; and standards define acceptable risk and reliability.

If you want to create a second illustration for this page (optional), consider a flowchart with these nodes: “Select pavement type” → “Estimate ESALs/axle spectra” → “Measure subgrade support + drainage” → “Compute required structure” → “Pick layer thicknesses” → “Performance checks + details” → “Finalize section.”

Illustration prompt (no image tag used): Create a clean flowchart titled “Pavement Design Workflow” with the steps above, include icons for trucks (traffic), soil (subgrade), water drop (drainage), and layers (structure); use an engineering blueprint style.

Relevant standards and design references

Pavement design is typically governed by a combination of national methods and agency-specific standards. The right reference depends on facility type, jurisdiction, and whether the project is new construction, reconstruction, or rehabilitation/overlay.

- AASHTO Pavement Design Guidance (AASHTO methods): Widely used framework for determining pavement structure from traffic, reliability, and support inputs; commonly encountered in agency SN-based and mechanistic-empirical workflows.

- FHWA pavement references: Practical guidance on pavement materials, performance, and best practices, including drainage and preservation concepts that strongly influence real-world pavement design outcomes.

- State DOT design manuals and standard details: The “governing document” for many projects—defines acceptable pavement types, minimum thicknesses, design traffic categories, subgrade treatment rules, and construction specifications.

- Local/municipal pavement standards: Often apply for subdivisions, local streets, and utility restoration; may require specific sections or material classes.

Always confirm which document is contractually governing the pavement design. Many agencies require a specific method, traffic category system, and minimum thickness rules that override generic examples.

Frequently asked questions

Pavement thickness is calculated by selecting a pavement type and design method, estimating design traffic loading (often ESALs), quantifying subgrade support and drainage, and then sizing layer thicknesses to meet reliability and performance targets required by the governing standard.

You typically need AADT, truck percentage or vehicle classifications, growth rate, directional and lane distribution, design life, and axle-load assumptions or equivalency factors so mixed traffic can be converted into a cumulative design loading.

Flexible pavements are common where faster construction and easier overlays are valuable, while rigid pavements are often preferred for heavy loading, high shear locations, or where longer structural life and slab performance are advantageous under local constraints.

Water reduces subgrade and base stiffness, accelerates damage, and can trigger pumping or stripping, so poor drainage can shorten pavement life dramatically even when structural thickness appears sufficient in calculations.

Summary and next steps

Pavement design is the structured engineering process of selecting a pavement type and calculating layer thicknesses so the pavement carries forecast traffic loads for a targeted design life under local environmental and drainage conditions. The “how” is a workflow: define the facility, estimate traffic loadings, characterize subgrade support and moisture behavior, select materials, compute required structure using the governing standard, and then translate that structure into buildable layer thicknesses with practical checks.

If you want a pavement design that holds up in the field, don’t stop at a thickness number. Make sure your design explains the mechanism: how the structure distributes load, how moisture is managed, and how the pavement will be maintained over time—especially at high-stress locations like intersections, industrial entrances, and transitions.

Where to go next

Continue your learning path with these curated next steps.

-

Flexible pavement design

Go deeper into asphalt layer selection, rutting and fatigue concepts, and practical overlay strategies.

-

Rigid pavement design

Learn slab thickness logic, joint design fundamentals, and common rigid pavement distresses and checks.

-

Transportation Engineering hub

Explore additional transportation engineering resources, design guides, and related topics.